The Nihongi Ryaku (日本紀略) records that in 963 Kuya, wishing to celebrate completion of Saiko-ji (西光寺/the current Rokuharamitsu-ji 六波羅蜜寺), held a huge memorial service, with 600 monks chanting the Wisdom Sutra by the banks of the Kamo River. 3/10

In the Nanboku-cho period (南北朝時代 1336-1392) it is recorded that lanterns were lit at the graves on Ryozen (霊山) & Toribe-no 鳥辺野) to welcome back the spirits of the dead. The details are sparse, & it is unclear if this was a regular event. 6/10

By the 14thC Manto-e (万燈籠-lit. 10,000 lanterns) ceremonies were prevalent in many temples at Obon. Some of these temples were located on Kyoto's mountainsides, but there is nothing to indicate the lanterns were arranged to be deliberately seen in the city. 7/10

After the devastation of the Onin War (1467-77), Kyoto was struck by natural disasters & epidemics. The population began to fear that the spirits of the thousands killed in the 10 year conflict lingered in the city, causing increasing calamity. 8/10

By around 1558 (Eiroku era-永禄期) the tradition of lighting increasingly oversized lanterns at the end of Obon was prevalent across the city. Neighbourhood associations organised Furyu Odori (風流踊り-lit. Elegant Dance) to coincide with this. 10/10

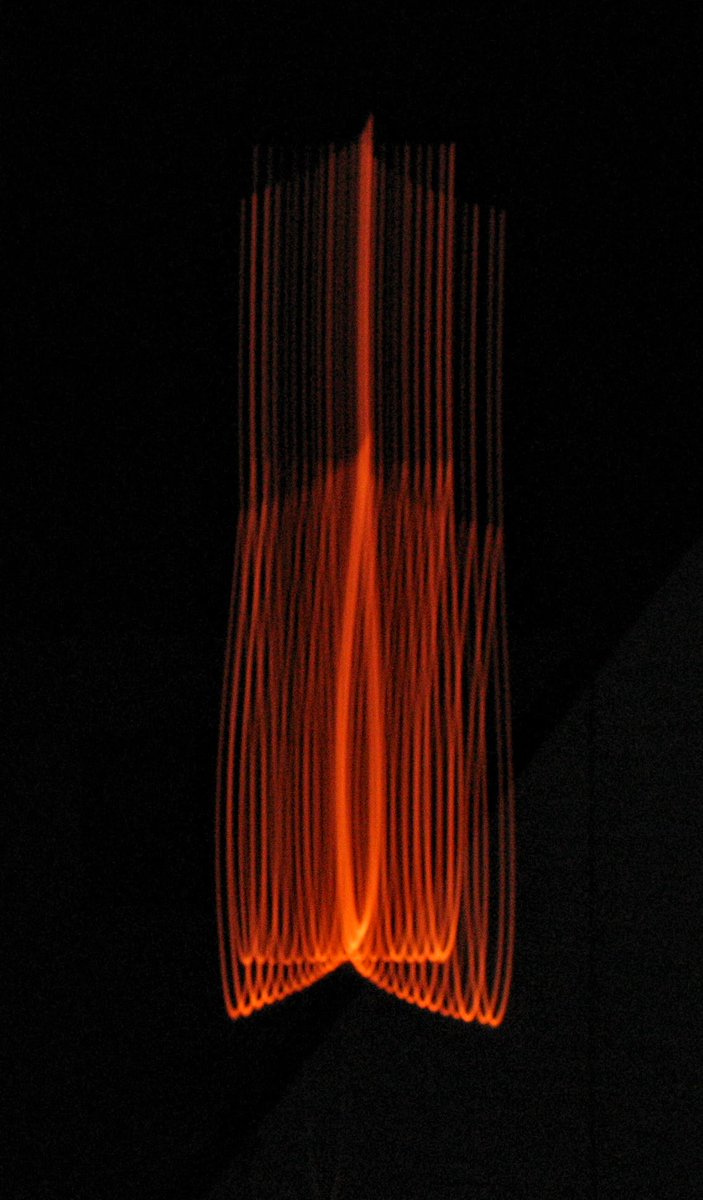

Along the Kamo River the villages of Hanase (花背), Hirogawara (広河原) & Kumogahata (雲ヶ畑) preserve torch lighting ceremonies called Matsuage (松上げ). These fire festivals perhaps most clearly show where the Gozan-no-Okuribi came from. 2/10

In 1802 the author Kyokutei Takizawa Bakin (曲亭/滝沢馬琴 1767-1848) describes in his work Jinju Tsukiryo Manroku (壬戌羇旅漫録) the reflection from hundreds of lanterns glistening like stars in the Kamo River (鴨川). 7/10

In the late Edo period there are descriptions of the public gathering at the Kamo-gawa's dry river bed, placing lanterns in the water to float away...literally sending the spirits of the dead back home (the netherworld could be reached beyond the sea). 9/10