As you may have heard, the U.S. borrows a lot of money in the form of bond, which we refer to as Treasuries.

Treasuries are considered to be among the safest financial assets that exist in the world.

When you lend money, typically, there are two ways that that loan can go bad.

The first is that the borrower just doesn't pay you back...

There is risk however from inflation. If you lend money to the government at 2%, you'll regret it if inflation goes to 4%, etc.

Now on a day to day basis, the price of bonds is always changing due to various things that happen.

For example, if good economic data comes out, people might perceive the future to be brighter. And they'll sell their bonds...

Or just suppose bad economic data comes out and people start to see the future as more grim. They see fewer growth opportunities. They see gluts of goods and falling prices. That also is likely to spur buying of safe assets and lower yields.

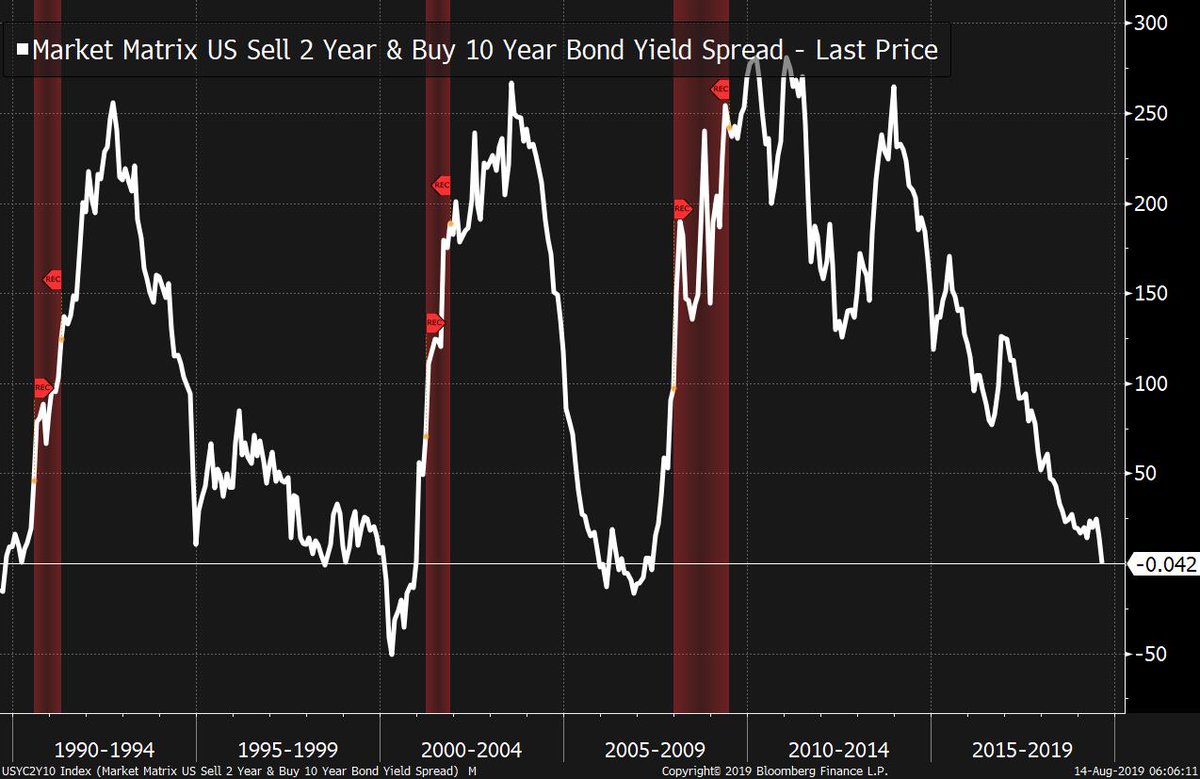

It's also the market saying that the Fed's current monetary policy stance is overly restrictive, given conditions that are materializing in the real economy.

Well, for one thing it's not inverted anymore, that happened very briefly yesterday, but it's not anymore.

Second, some argue that there are factors that make it different this time.

Also in the past, the inversion was more a direct result of the short end rising, as opposed to long-end falling.