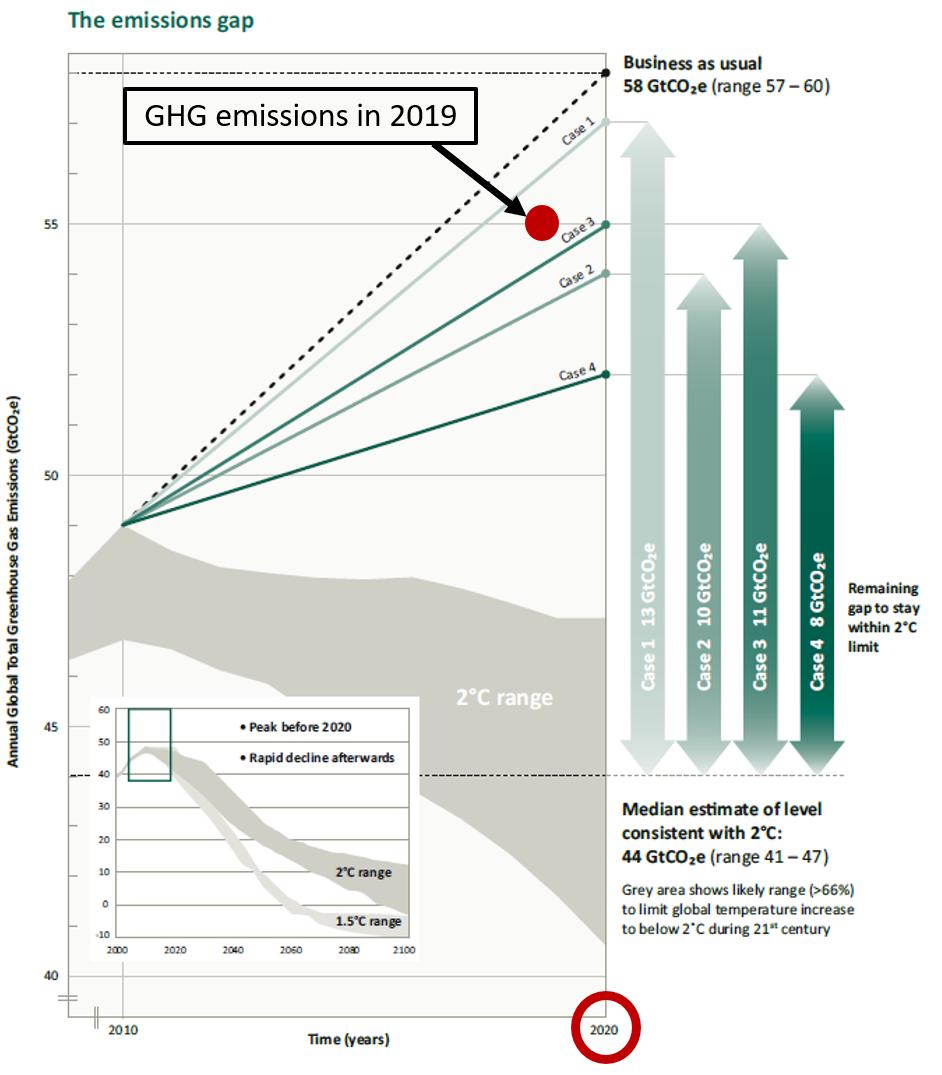

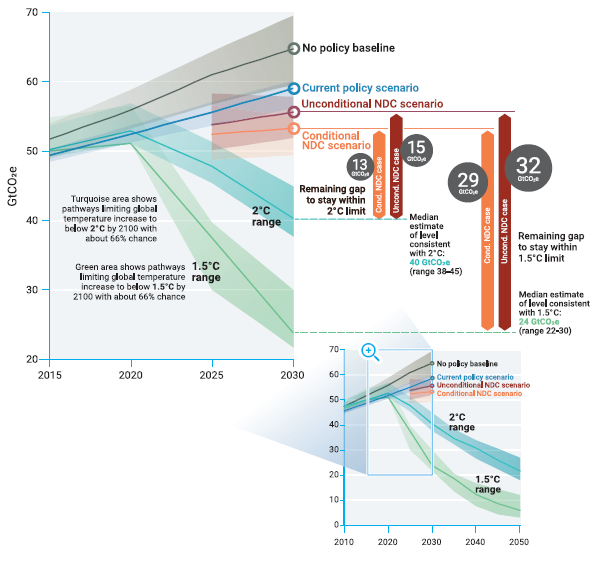

On the massive task ahead to break the rising trend in global greenhouse gas emissions, and to turn it around to rapid reductions.

unenvironment.org/resources/emis… #COP25

[btw, the new Commission already aims for -50..-55%]

zero emission targets domestically and 65

countries and major subnational economies,

such as the region of California and major cities

worldwide, have committed to net zero emissions

by 2050.

submitted to the UNFCCC have so far committed

to a timeline for net zero emissions, none of which

are from a G20 member

recently passed legislation.

The other 15 G20 members have not yet committed to zero

emission targets.

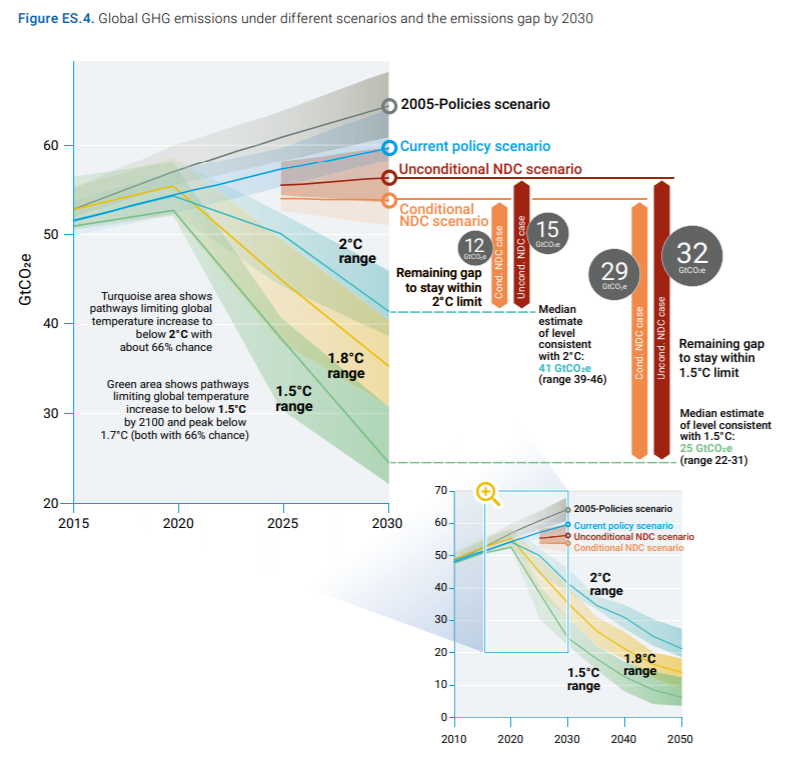

Current Paris commitments (NDCs) would lead to 4-6 billion tCO2 less emissions by 2030, compared to current policies. But that's only enough to stabilize global emissions at a very high level.

[That's a climate disaster scenario, just to be sure]

average over the 2020–2050 time frame, depending

on how rapid energy efficiency and conservation

can be ramped up.

potential to deliver significant emissions reductions:

● Phasing out coal for rapid decarbonization of energy

● Decarbonizing transport with a focus on electric mobility

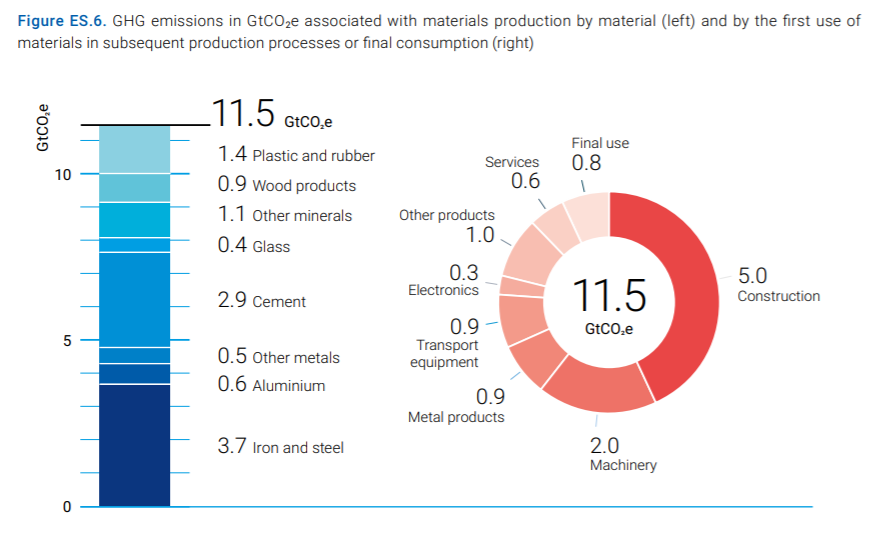

● Decarbonizing energy-intensive industry

● Avoiding future emissions while improving energy access

challenging and will meet a number of economic,

political and technical barriers and challenges. But:

● More intensive use, longer life, component reuse, remanufacturing and repair as strategies to obtain more service from material-based products.

reduce the need to produce more emission-intensive

primary materials.

and more materials here: unenvironment.org

I guess now it's a circular one ;)