Swansea City’s 2019/20 accounts covered a season when they finished 6th in the Championship under head coach Steve Cooper, thus reaching the play-offs, but were eliminated in the semi-final by Brentford. Some thoughts in the following thread #Swans

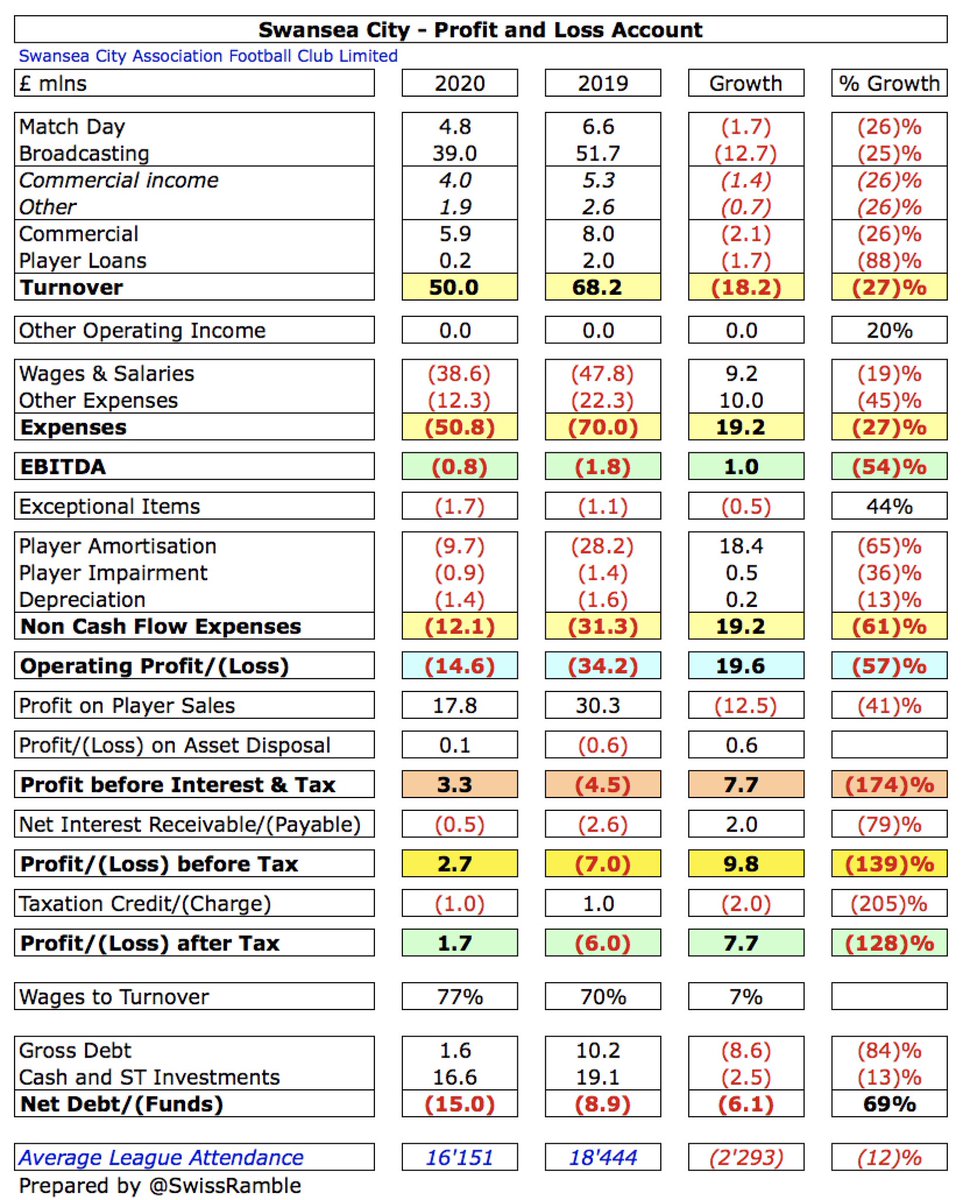

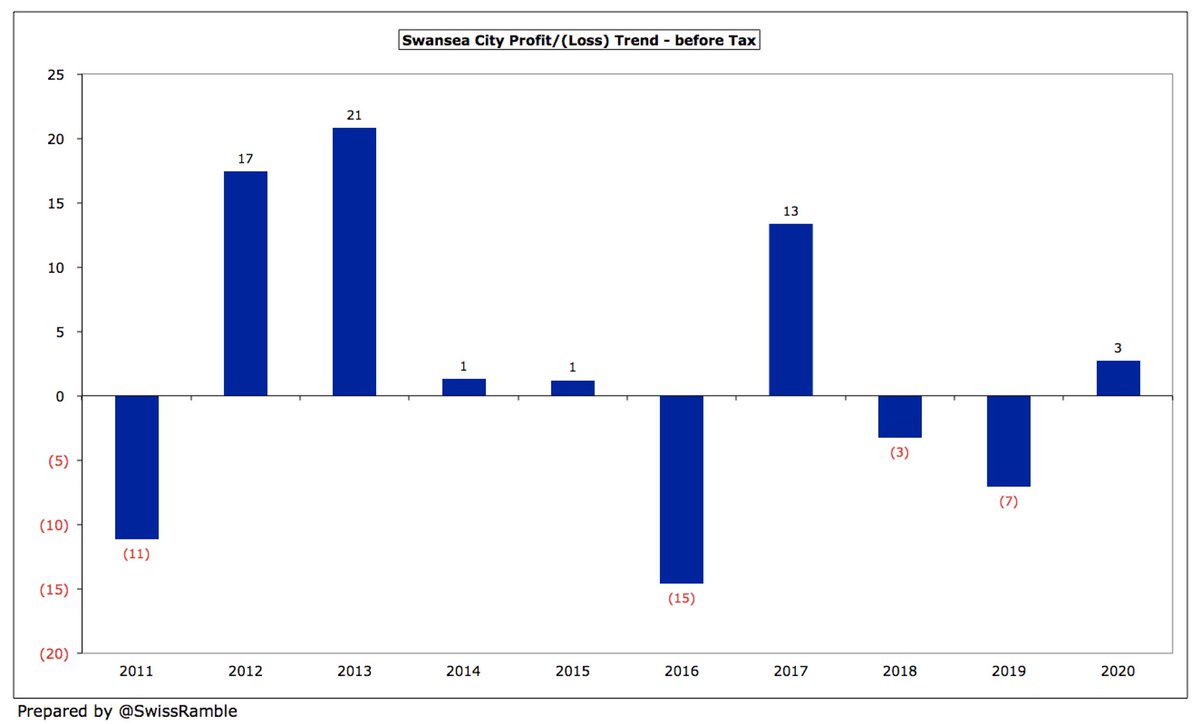

#Swans swung from a pre-tax loss of £7m to a profit of £2.7m, despite revenue falling £18m (27%) from £68m to £50m and profit from player sales dropping £12m (41%) from £30m to £18m, as total expenses were reduced by £40m (38%). Profit after tax was £1.7m.

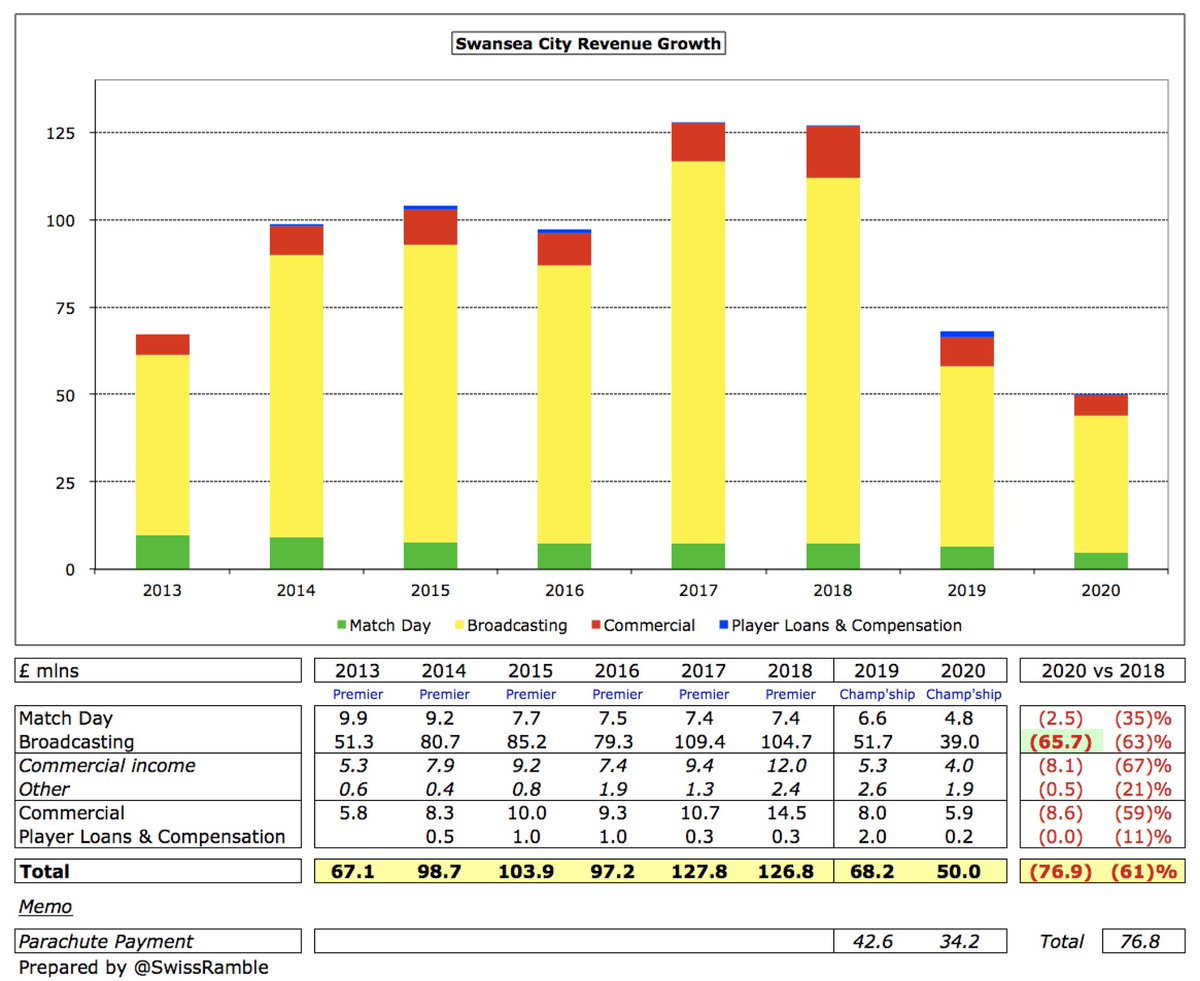

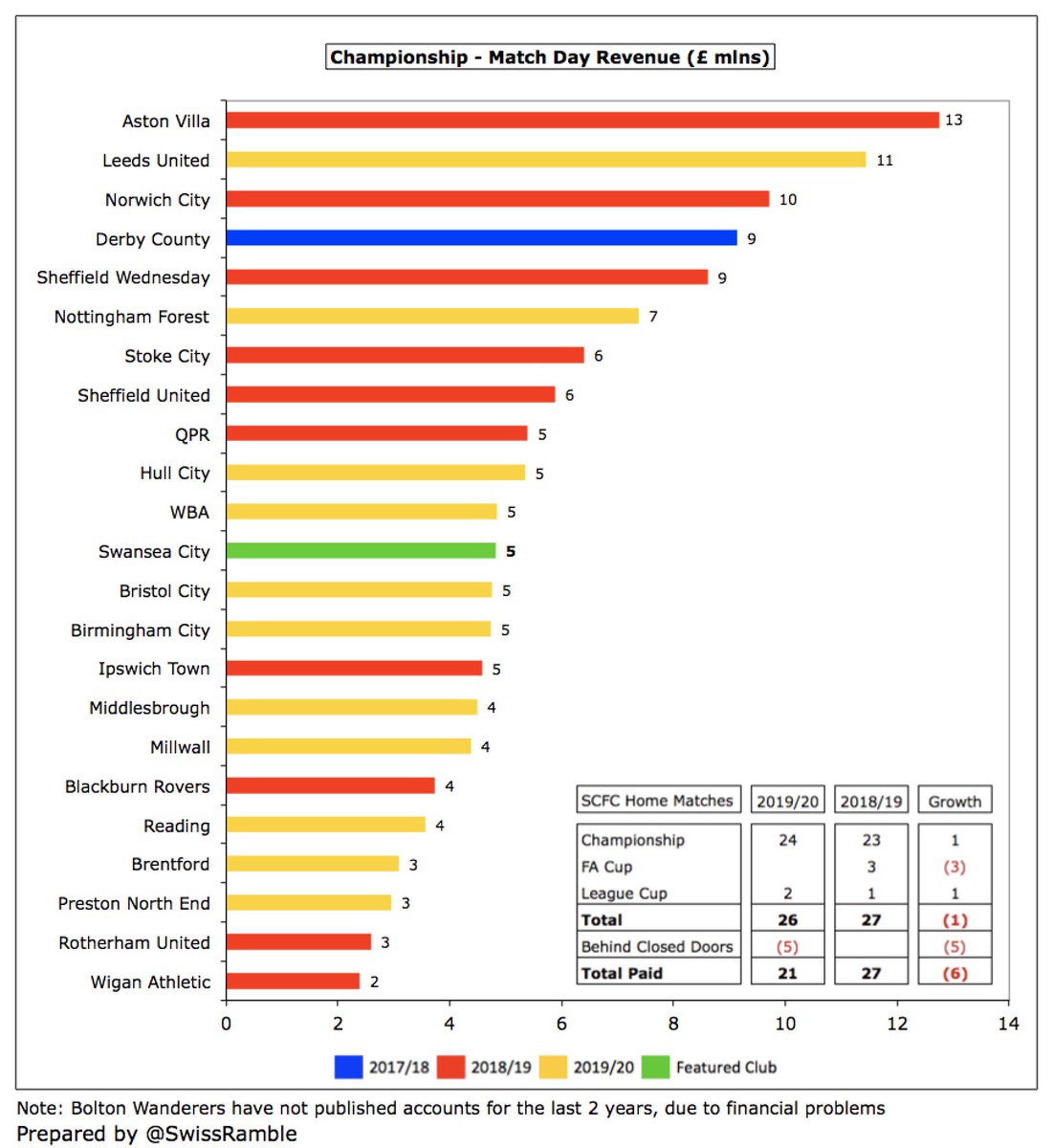

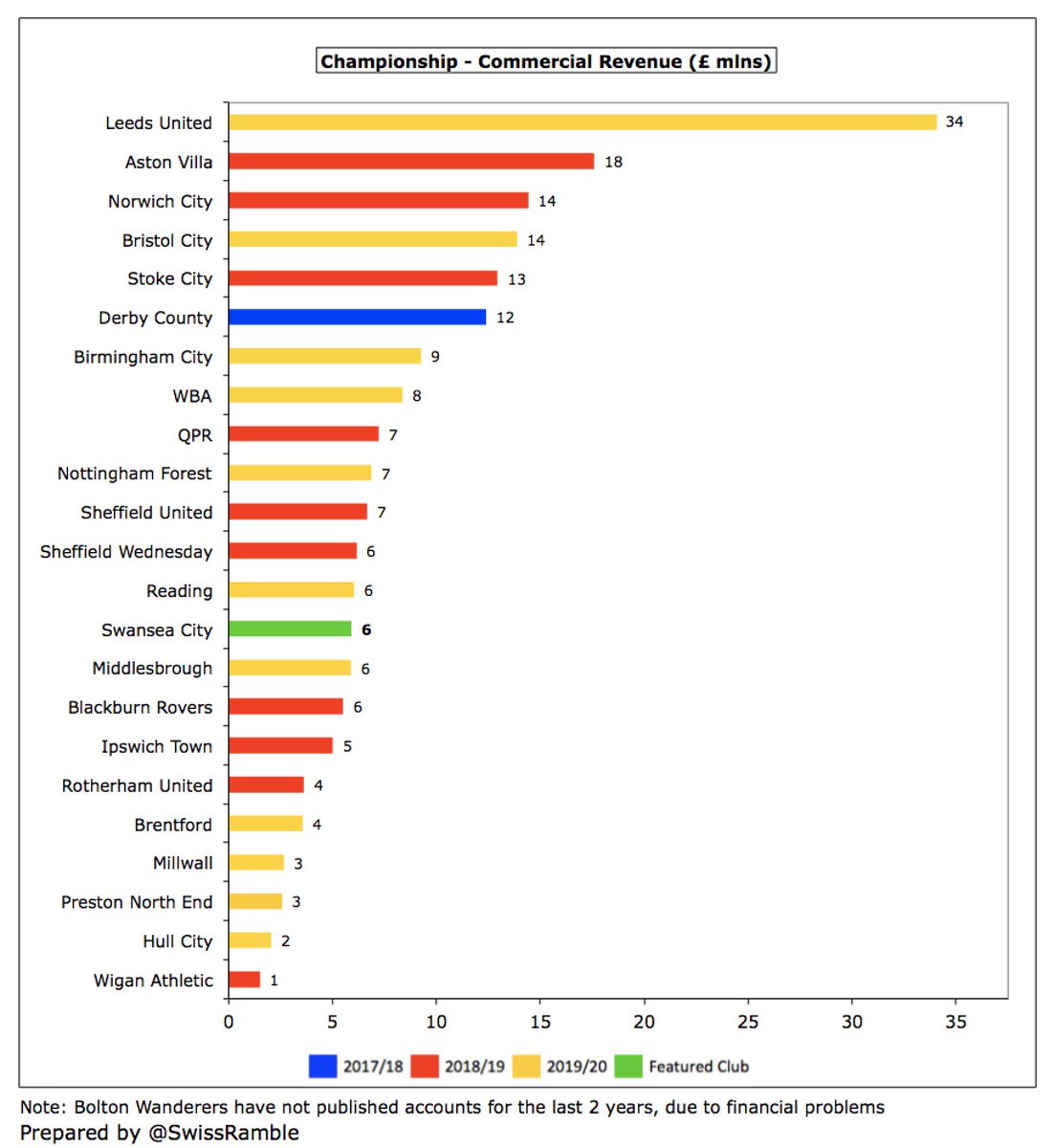

The main reason for #Swans £18m revenue reduction was broadcasting, which dropped £13m (25%) from £52m to £39m, mainly due to lower parachute payment, though commercial was also down £2m (26%) to £6m and match day fell £1.7m (26%) to £4.8m. Player loans were down £1.7m to £0.2m.

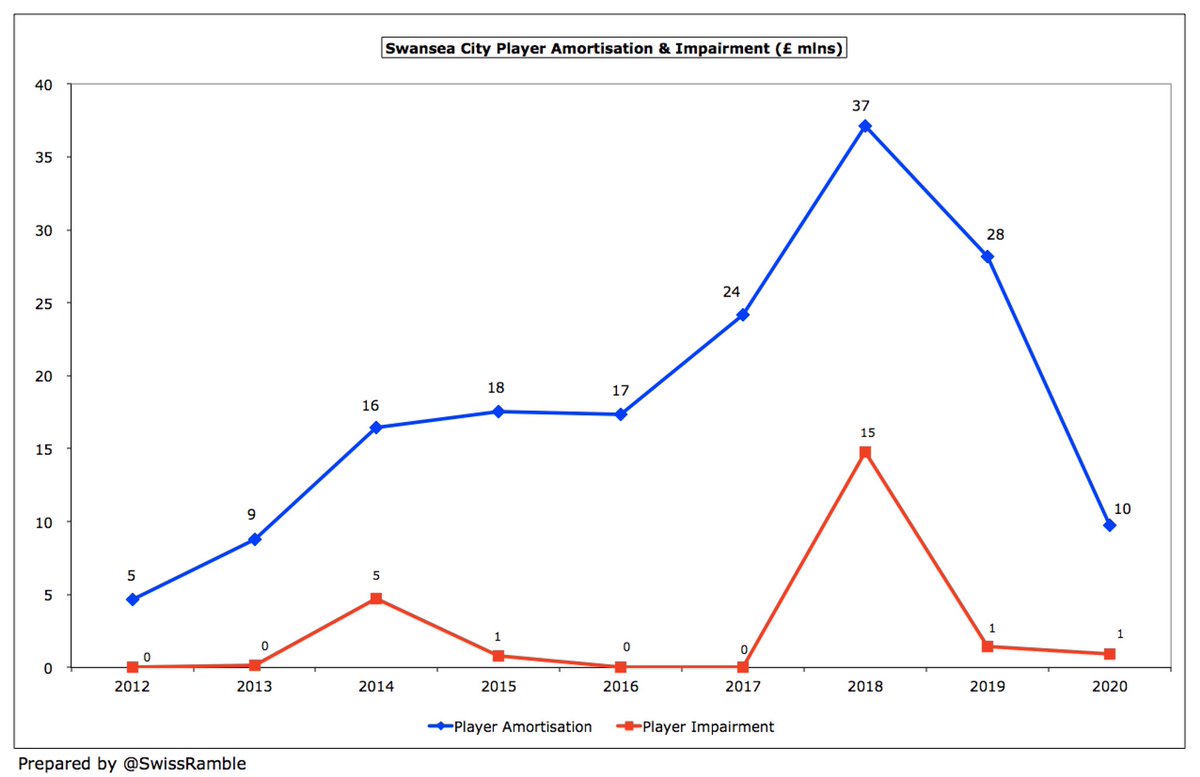

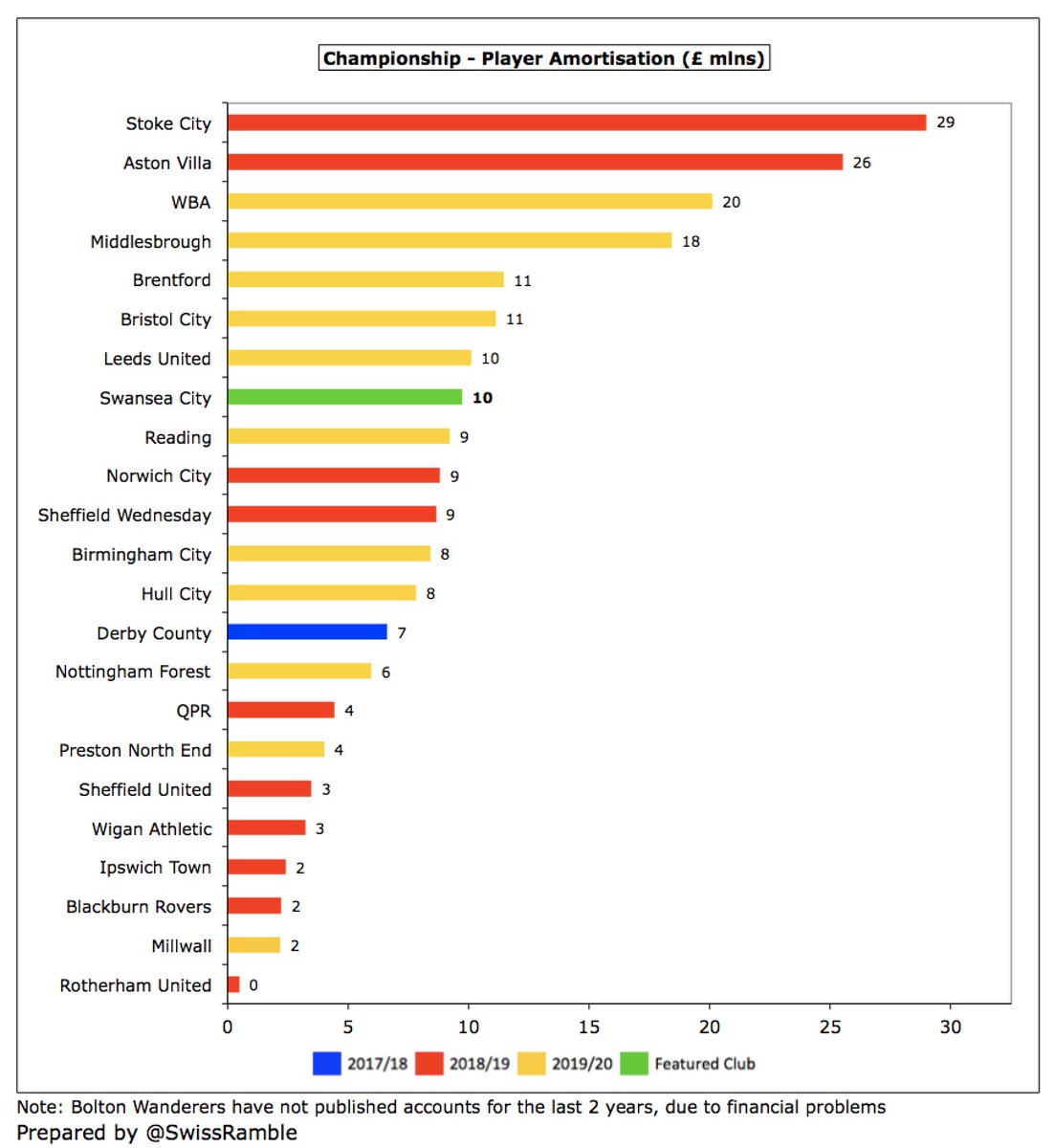

To offset the steep revenue reduction, #Swans cut the wage bill by £9m (19%) from £48m to £39m, while player amortisation/impairment was down £19m (64%) to £11m, other expenses decreased £10m (45%) to £22m and net interest payable fell £2.0m to £0.5m.

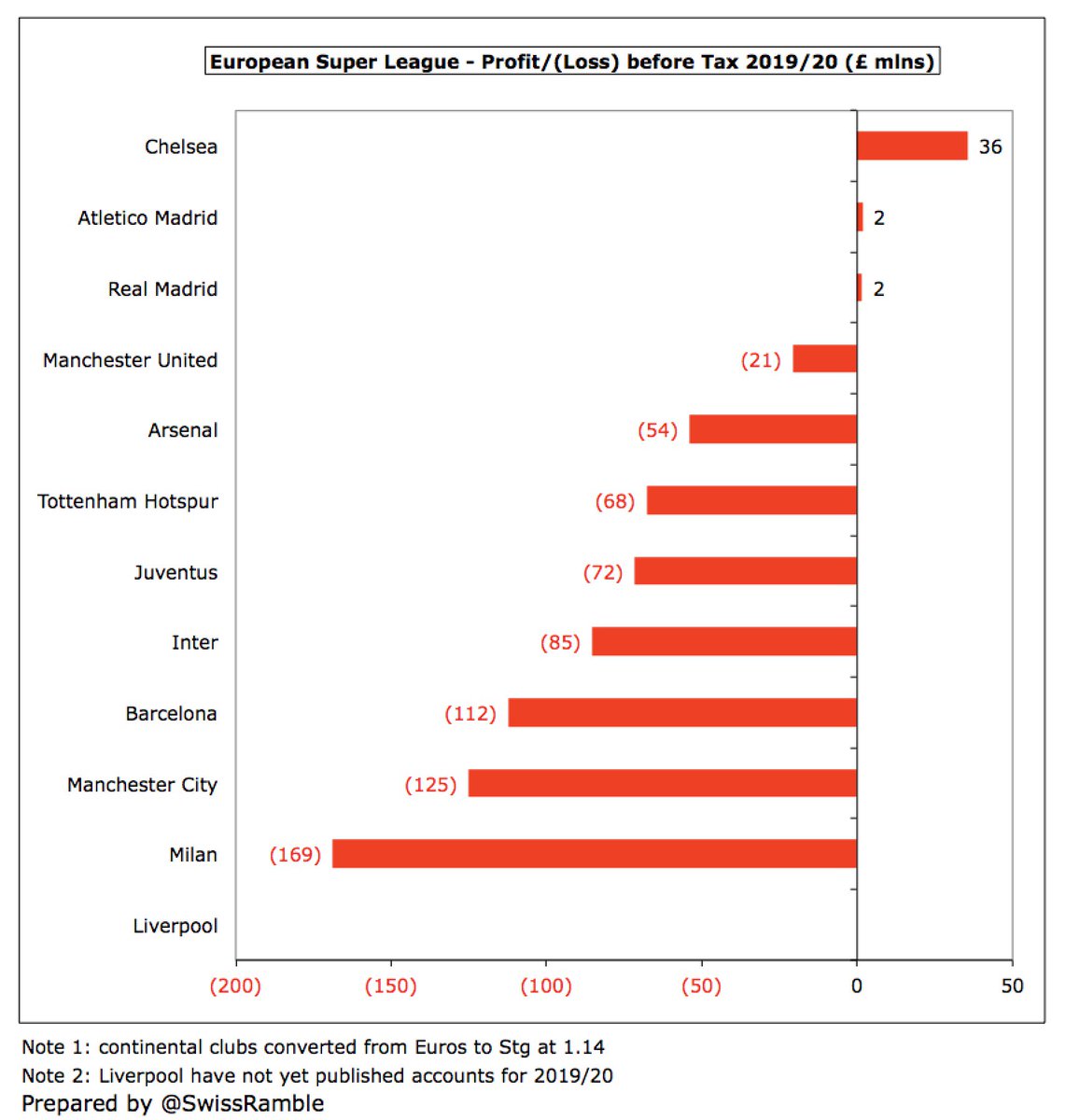

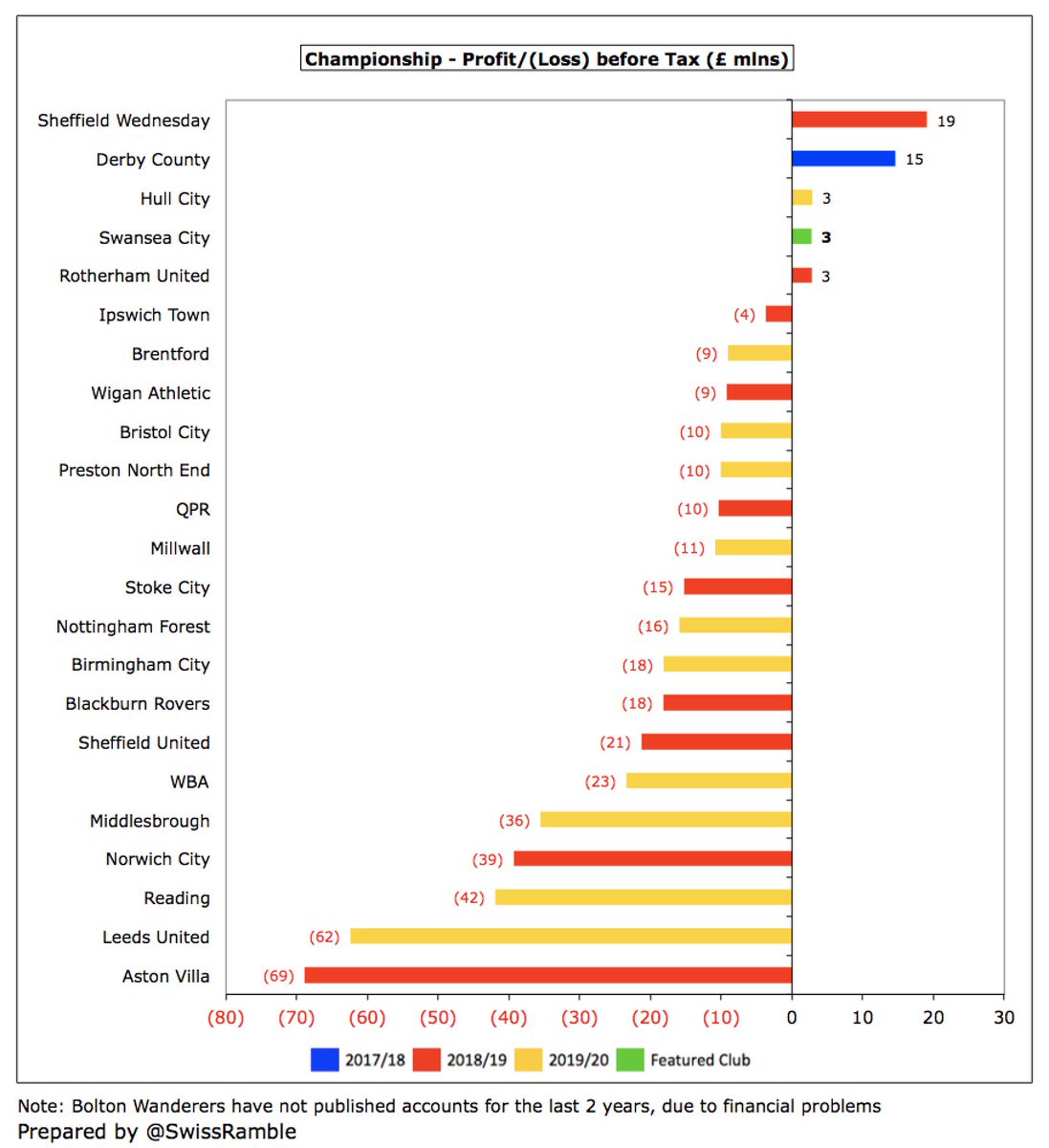

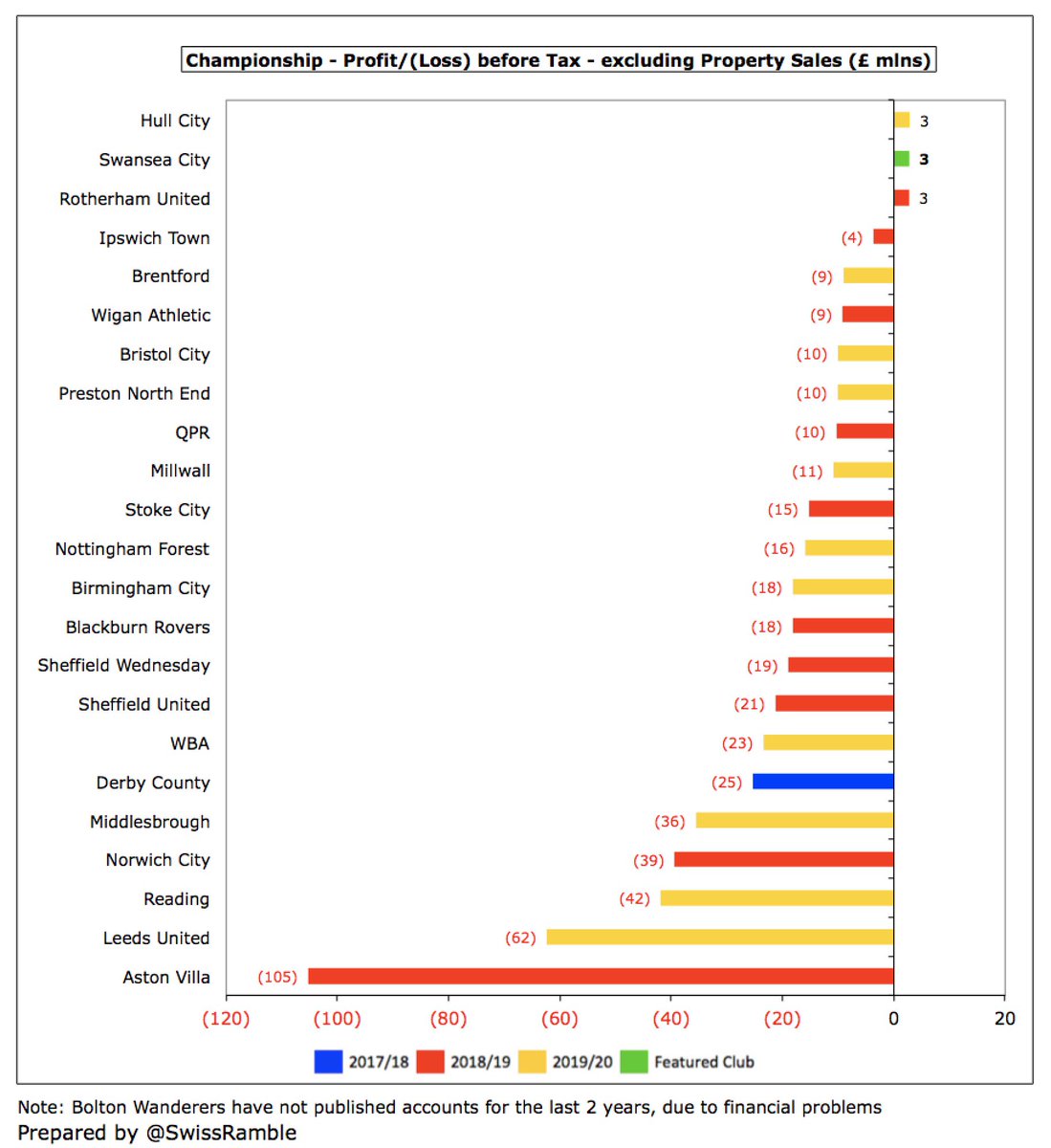

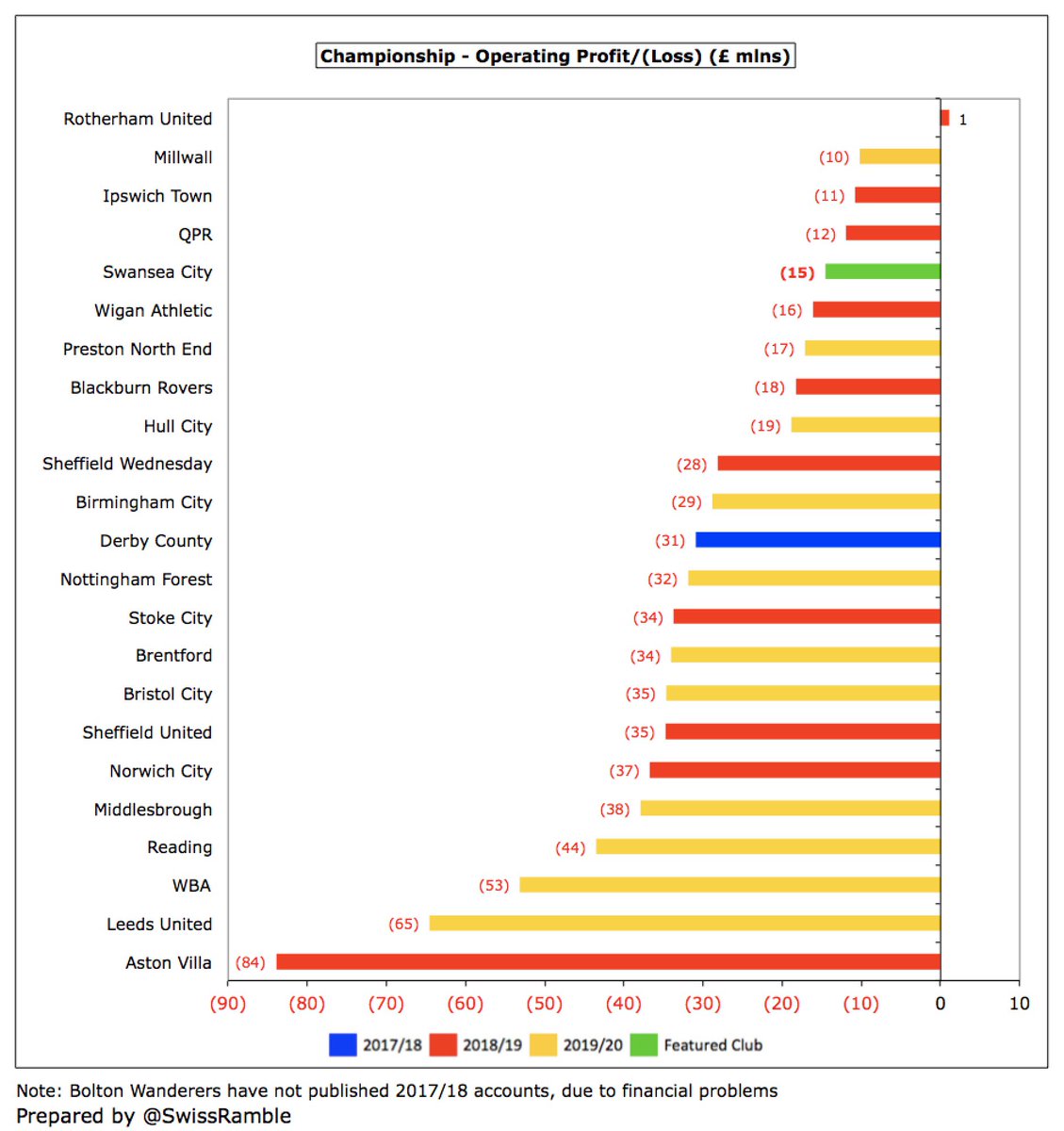

The fact that Swans managed to make a £3m profit is a noteworthy achievement. Only one other Championship club is also profitable in 2019/20 to date (#HCAFC £3m), while some have reported huge losses, including Leeds United £62m, Reading £42m, Middlesbrough £36m and WBA £23m.

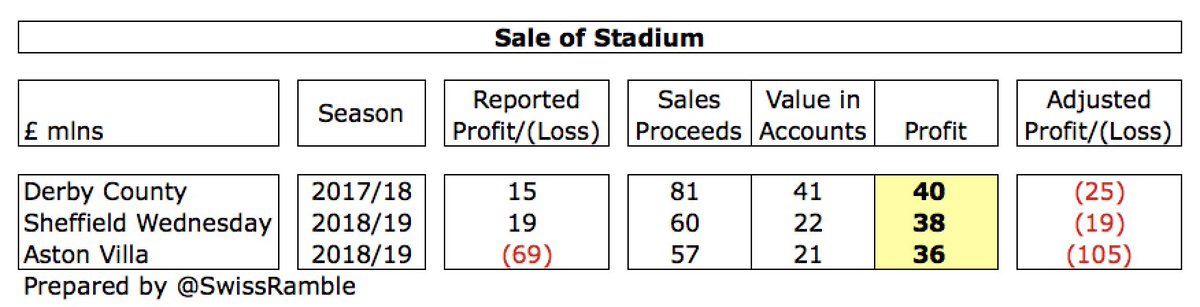

It is also worth noting that some clubs’ most recent figures have been boosted by the sale of stadiums, training grounds and land, especially #DCFC £40m, #SWFC £38m and #AVFC £36m, so their underlying profitability was even worse than reported.

Excluding property sales, only 2 Championship clubs are profitable in 2019/20 to date (#Swans and #HCAFC, with £3m apiece). Very few clubs manage to make money in this ultra-competitive division, though largest losses often from promoted clubs – including hefty promotion bonuses.

#Swans have not quantified the effect of COVID-19, though this obviously impacted gate receipts, retail and hospitality revenue, even though they took advantage of government support schemes. The full economic effect will not be clear until next year’s accounts are published.

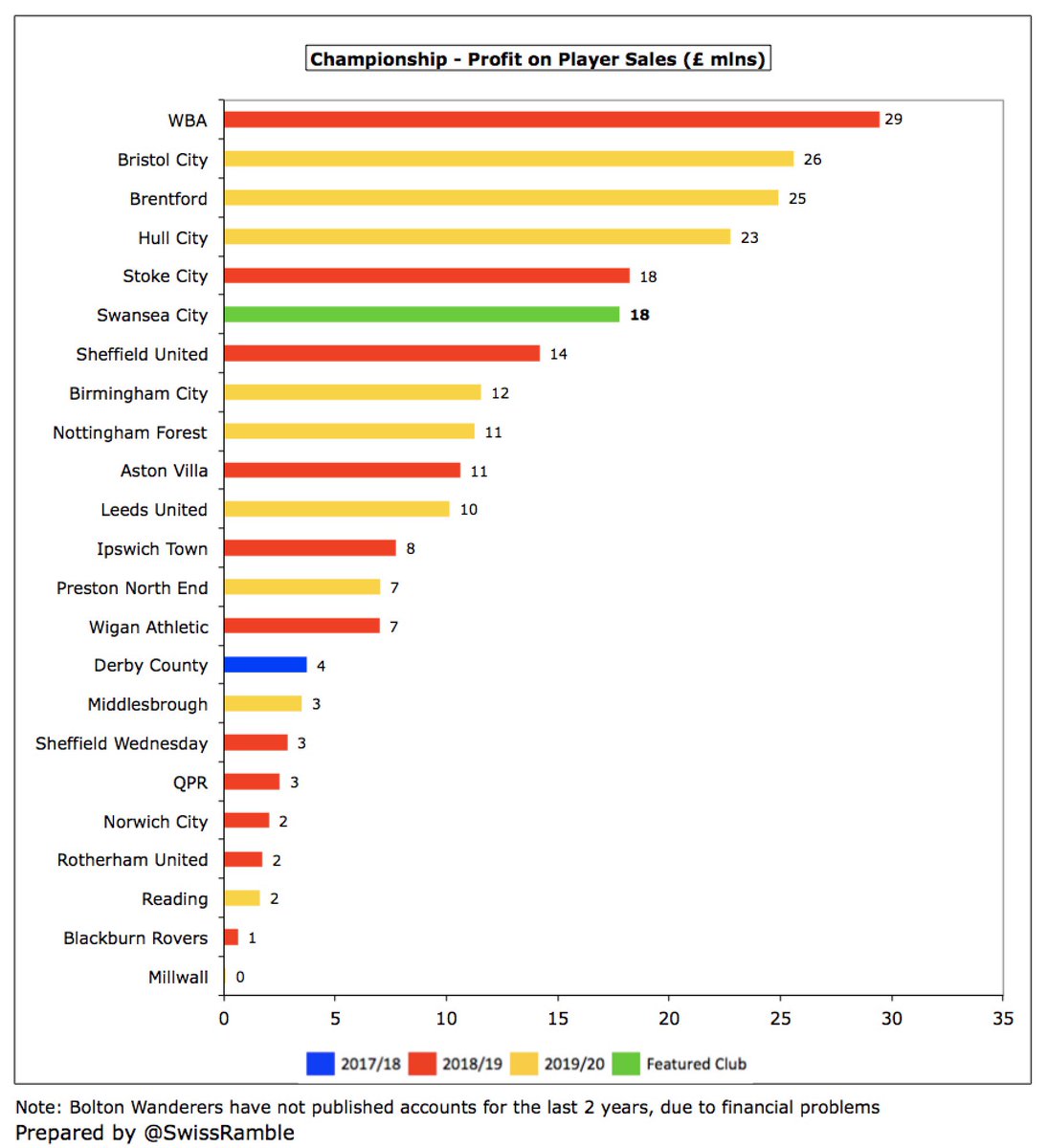

#Swans noted that £18m profit from player sales was “used to fund the overall operating loss”, though down from prior year’s £30m. Mainly came from sale of Oli McBurnie to #SUFC. Still pretty good, but a fair bit lower than Bristol City £26m, Brentford £25m and Hull City £23m.

#Swans have now been profitable six times in the last nine years. In the seven seasons in the Premier League (between 2012 and 2018), profits amounted to £36m. Even the last two seasons in the Championship have only resulted in a small net loss of £4m.

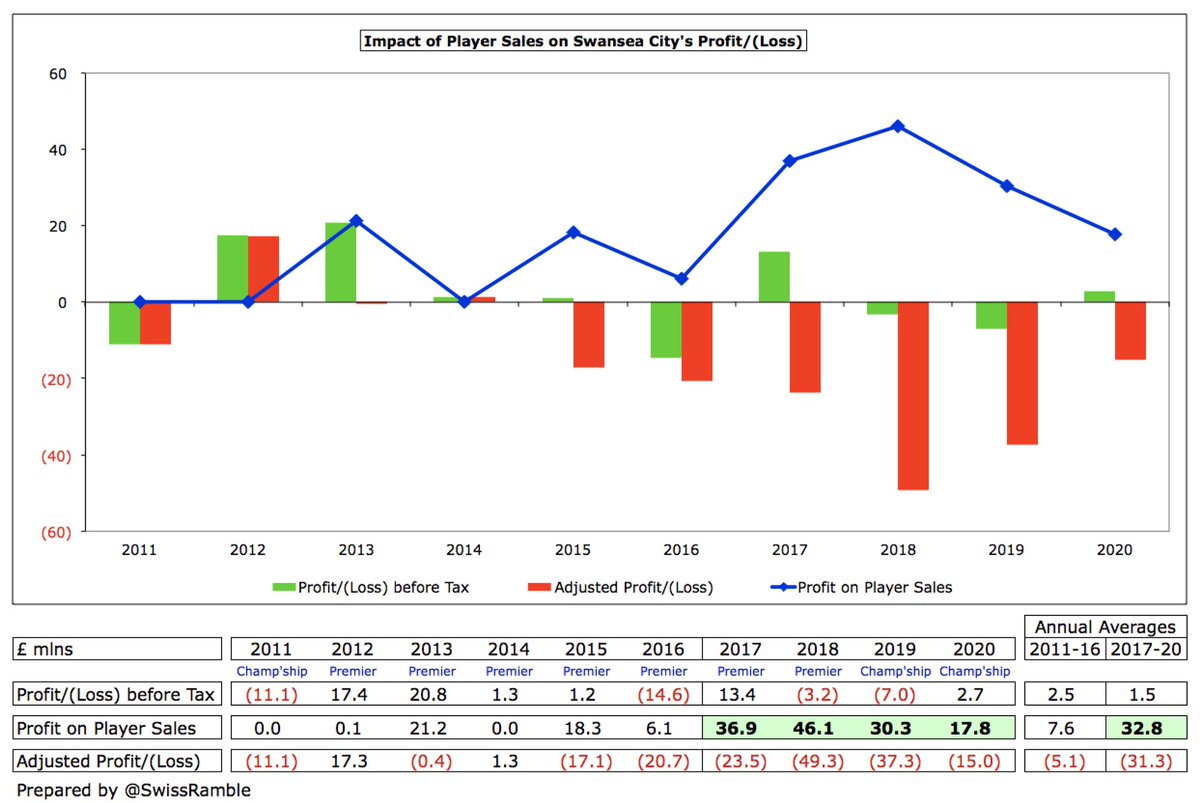

However, #Swans have become increasingly reliant on player sales with average annual profit increasing to £33m in the last 4 seasons, compared to just £8m in the preceding 6 years. This season will similarly benefit from Joe Rodon’s sale to #THFC.

Former #Swans chief executive Trevor Birch noted, “If we had not sold players, we would have reported significantly higher losses. Profit on player sales has gone on funding player wages, running the Academy and the significant operating costs of a top-level football club.”

If #Swans forecast player sales are not achieved, they would need to find further sources of funding to maintain cash flow. The auditors said, “This represents a material uncertainty which may cast significant doubt about the club’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

#Swans operating loss (i.e. excluding player sales and interest) improved from £34m to £15m, which is actually one of the better performances in the Championship. Almost every club in this division posts substantial operating losses, i.e. half of them are above £30m.

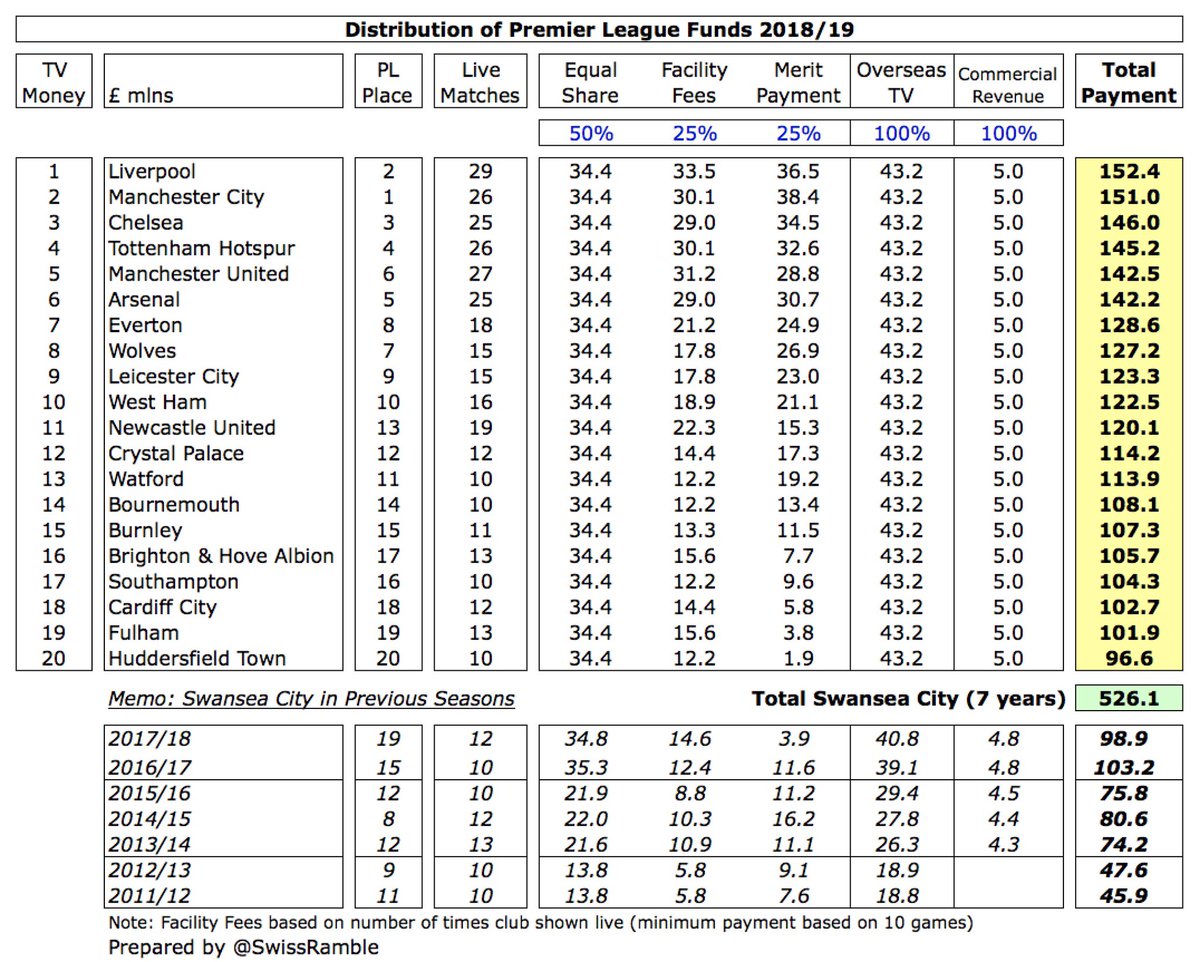

Since relegation from the Premier League, #Swans revenue has dropped £77m (61%) from £127m in 2018 to £50m in 2020, very largely due to less TV money in the Championship, though commercial is also down £9m (56%) in the last two years.

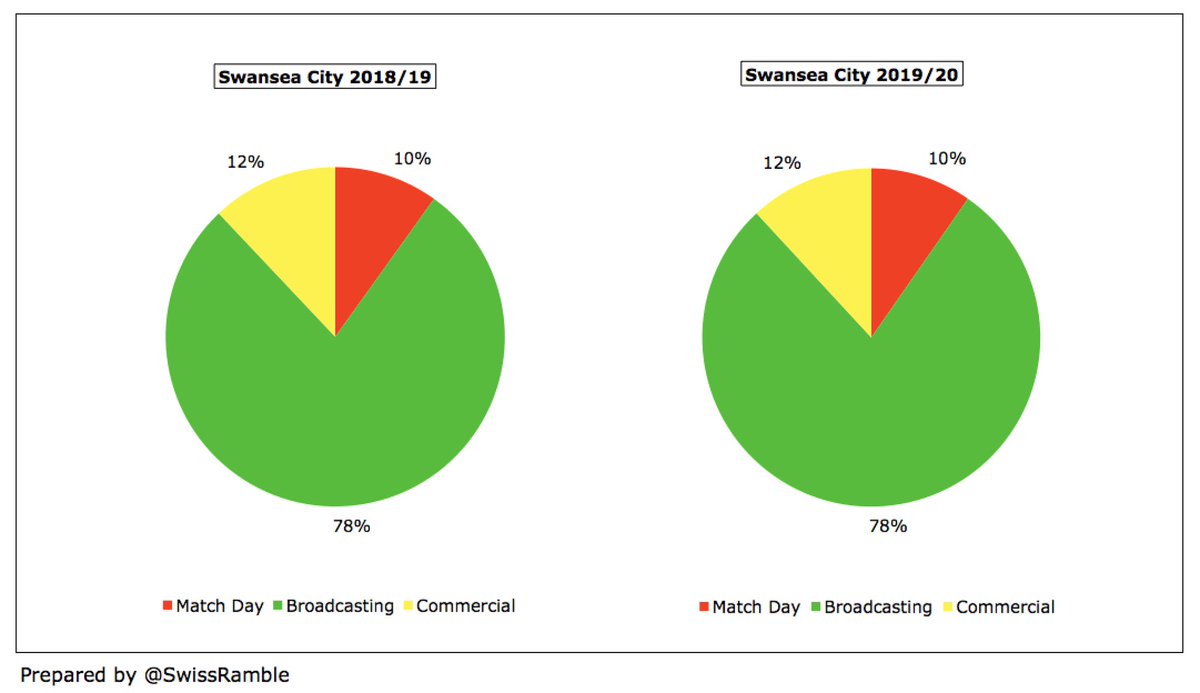

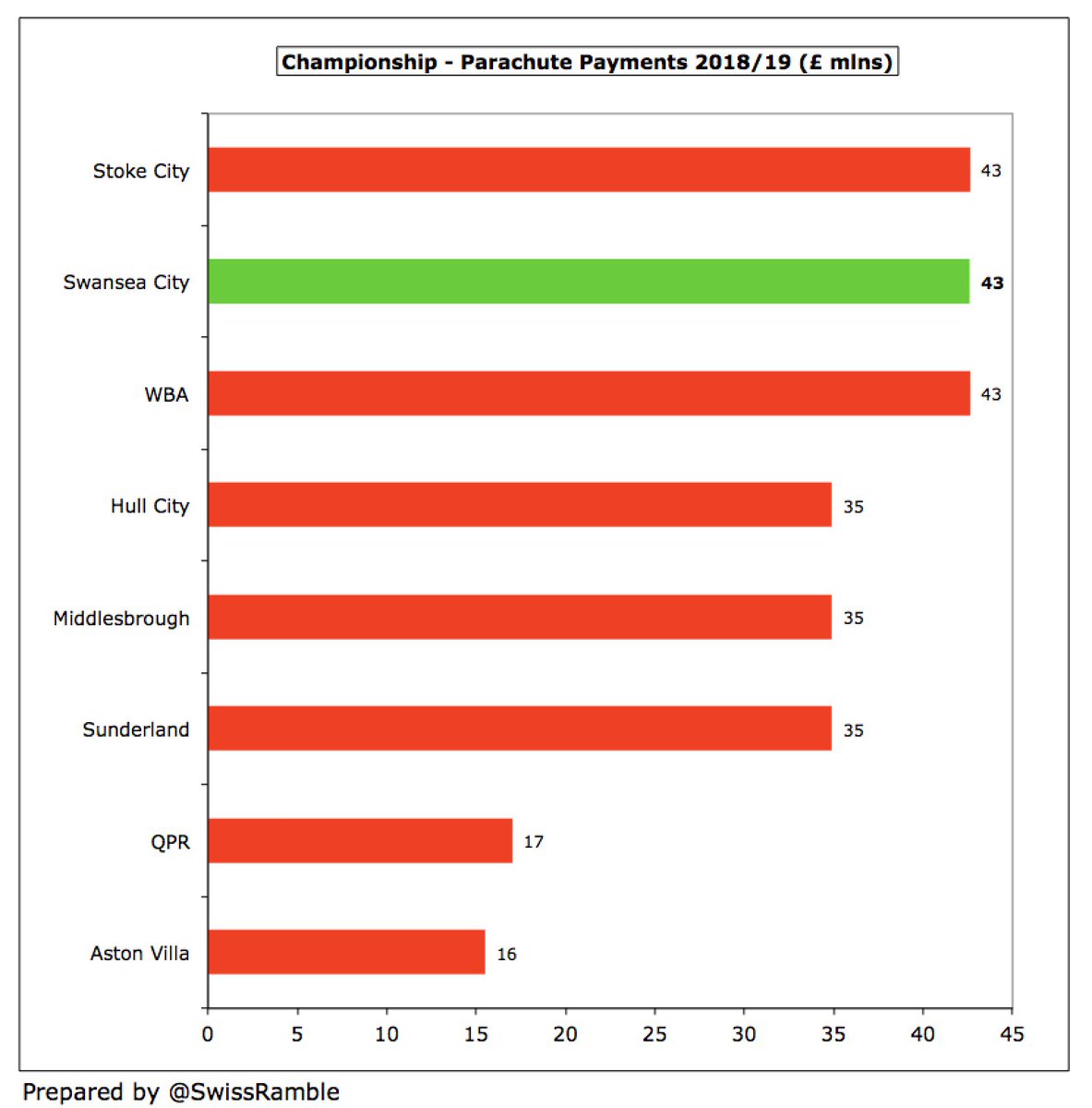

#Swans revenue decrease last season was mainly driven by parachute payment dropping from £43m to £34m, though broadcasting still accounts for 78% of total revenue. The parachute will further fall this season to £15m, then down to zero from 2021/22.

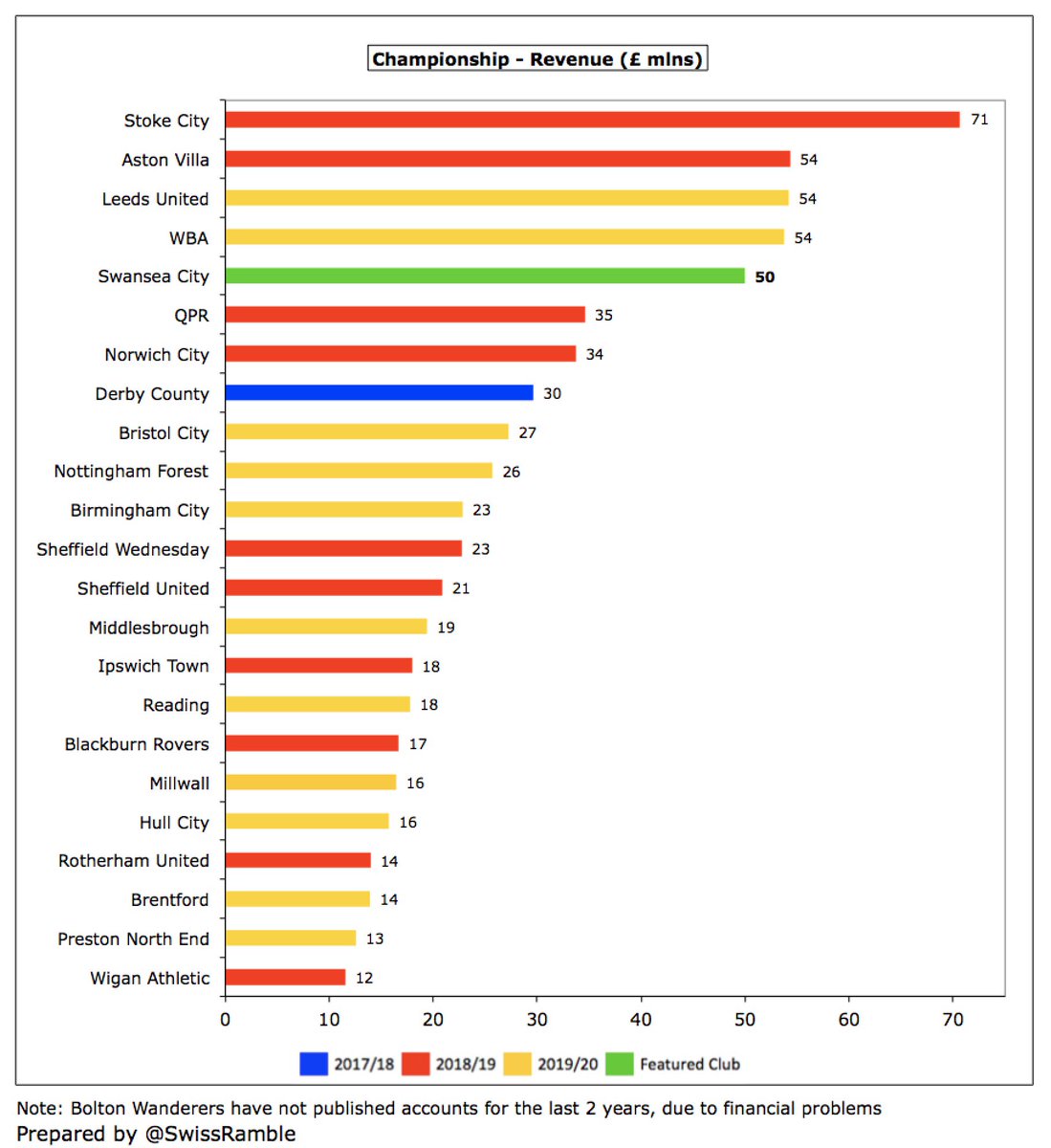

Even after the fall, #Swans £50m revenue was still one of the highest in the Championship, through they were overtaken by #LUFC (massive commercial income). They will also be behind the three clubs most recently relegated from the Premier League, when they publish their accounts.

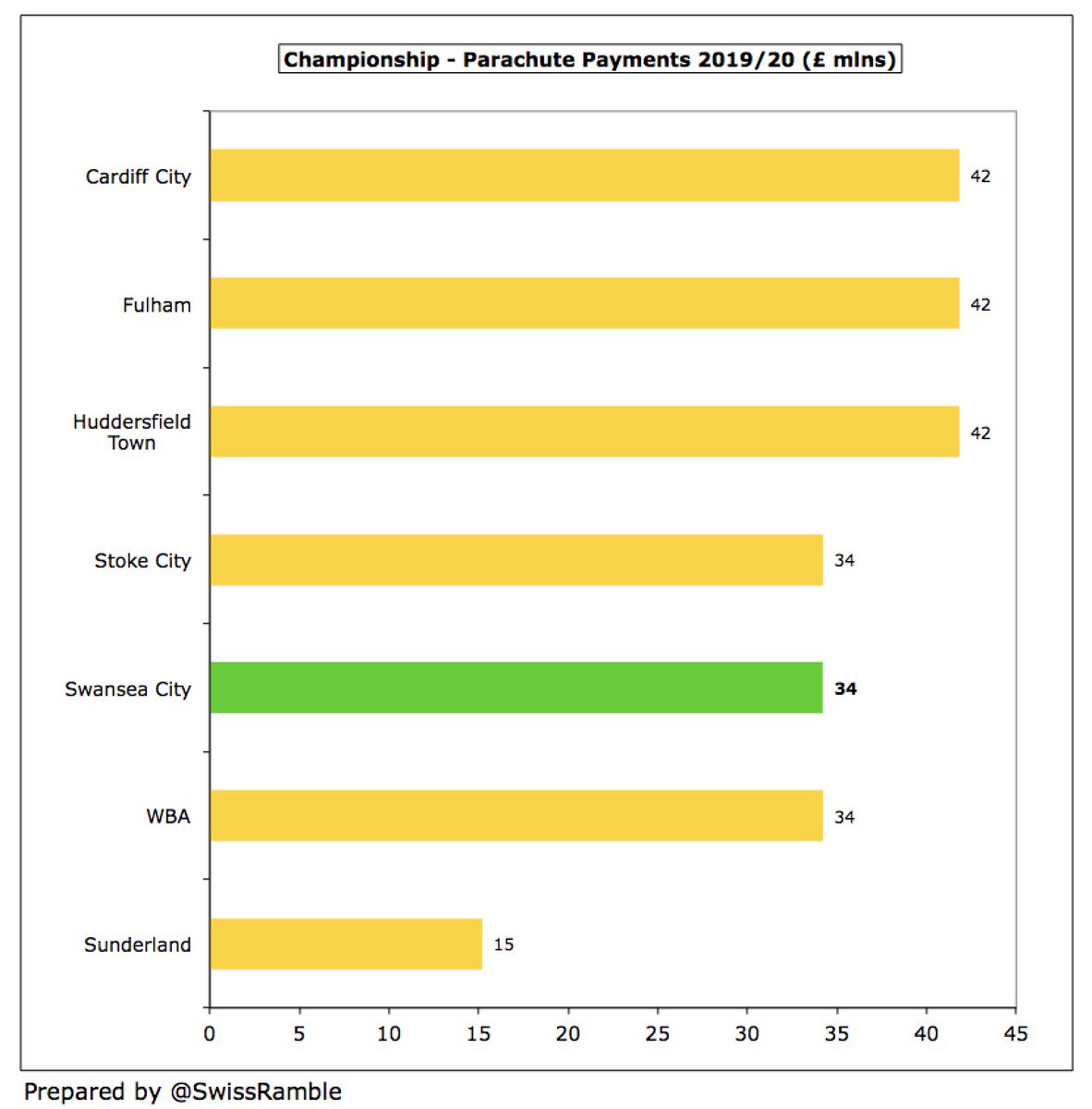

Obviously, #Swans benefited from £34m parachute payment, though this was down from £43m in the previous season. Six other clubs received parachutes in 2019/20, led by Cardiff City, #FFC and #HTAFC (£42m), followed by Stoke City and WBA (£34m)

If parachute payments were excluded, #Swans revenue would fall to £20m (£34m parachute replaced by £4.5m solidarity payment). This would have placed them mid-table in the Championship with the gap to the top club (#LUFC £54m) increasing to £34m.

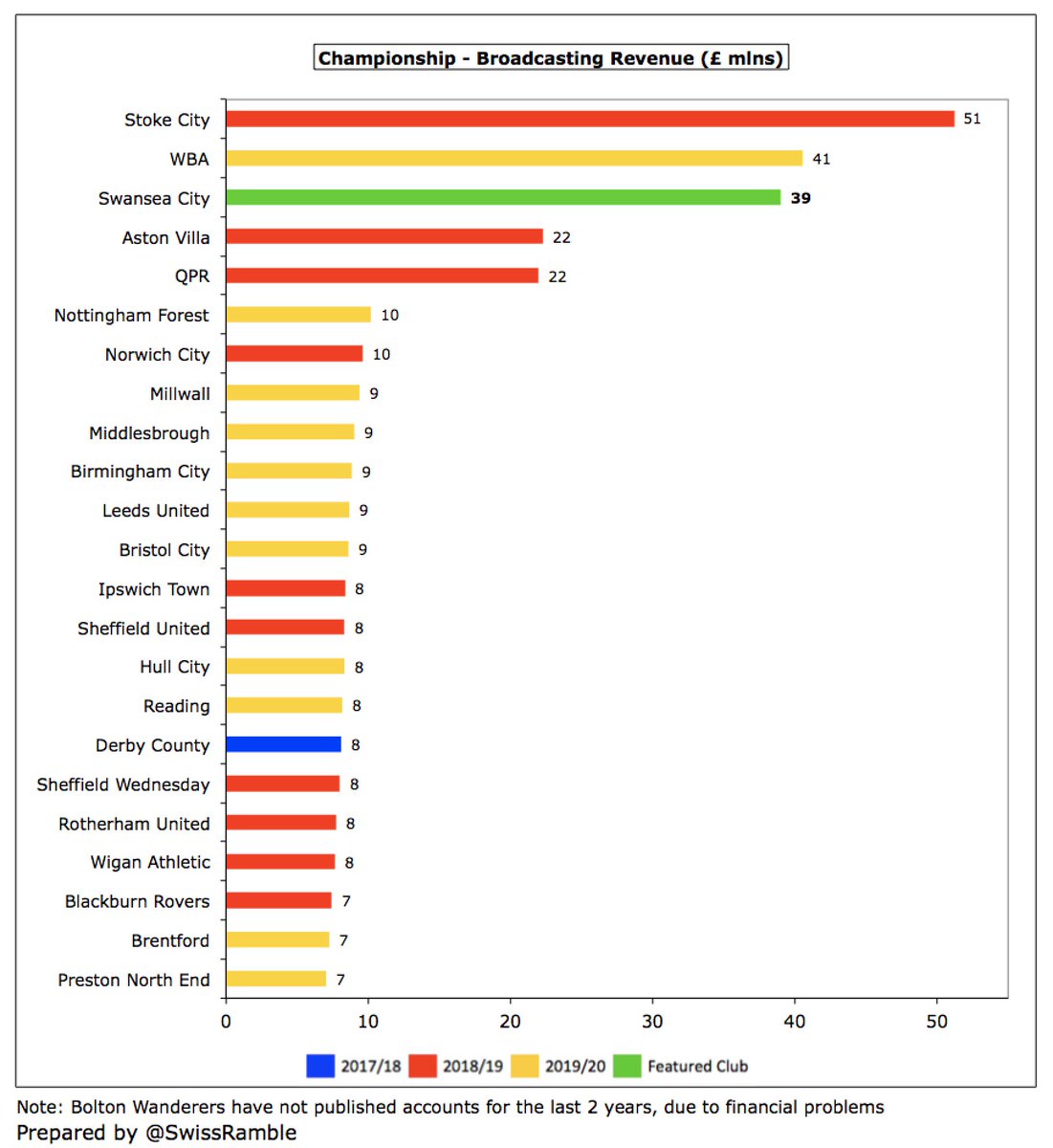

#Swans broadcasting income fell £13m (25%) from £52m to £39m, due to smaller parachute payment, which is the club’s lowest since 2011. Most Championship clubs earn £7-10m, but there is a significant gap to those with parachute payments (e.g. Stoke City received £51m in 2018/19).

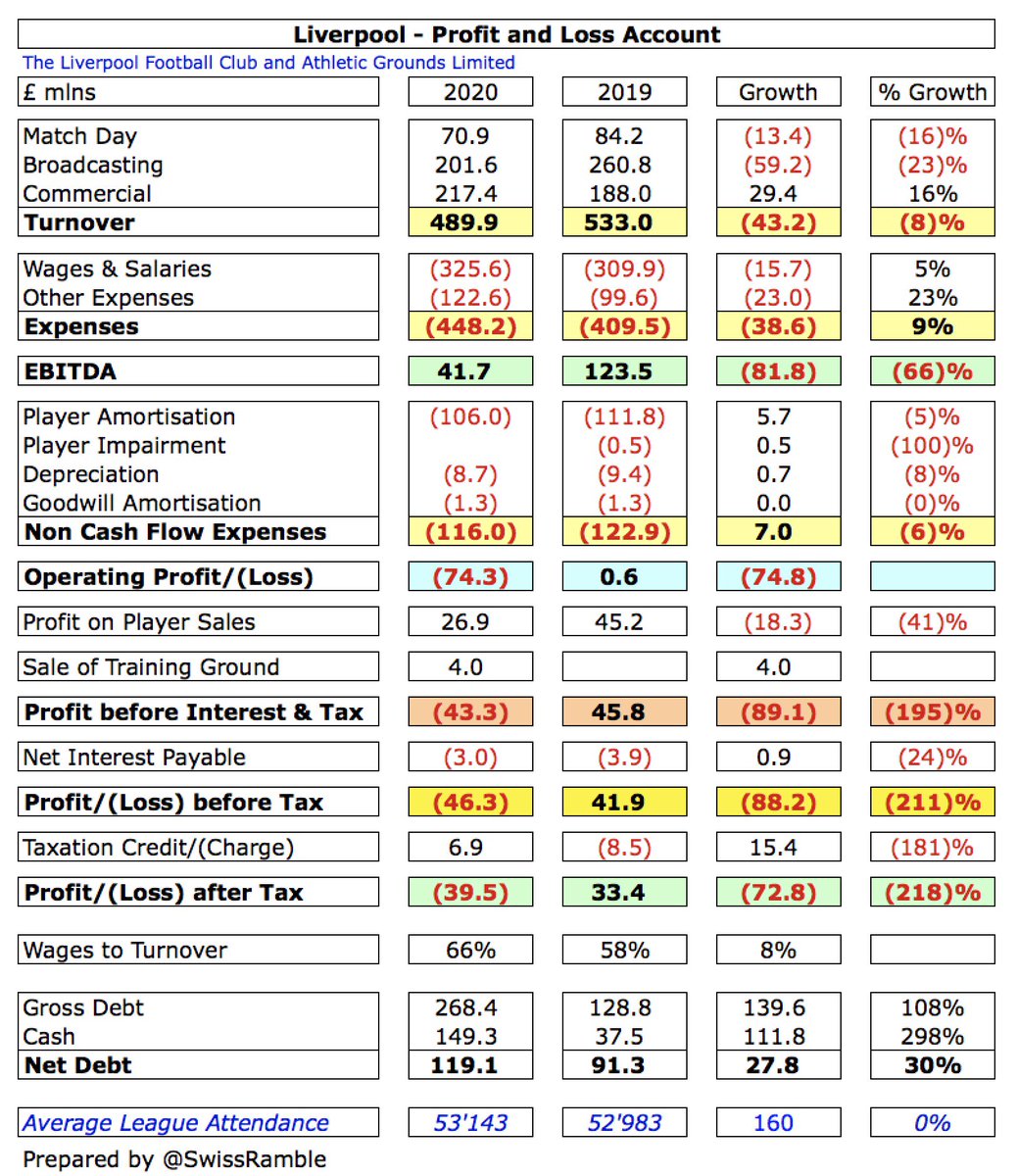

Of course, #Swans would receive much more broadcasting money if they manage to reach the Premier League this season via the play-offs. Even last place in 2018/19 received £97m, while the new TV deal from 2019/20 onwards is 8% higher (before COVID rebate)

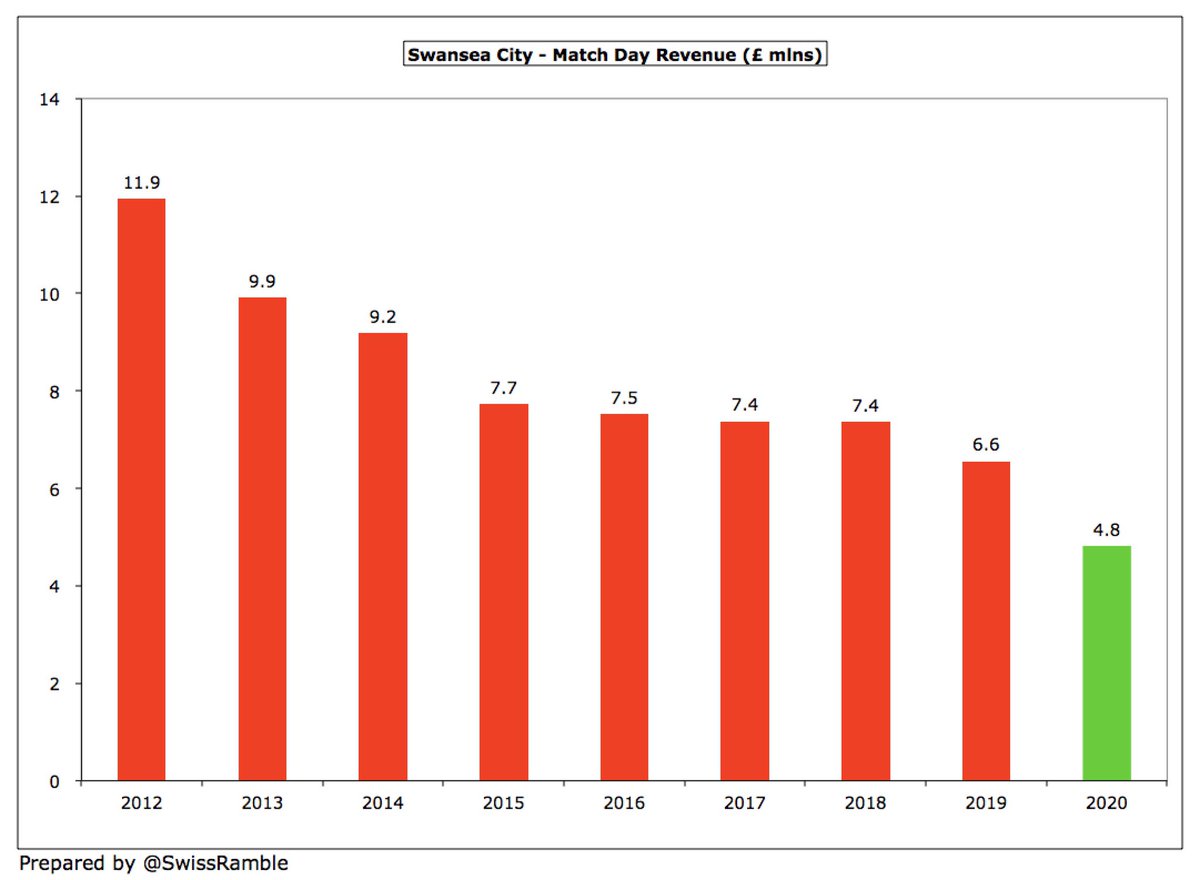

#Swans match day income fell £1.8m (26%) from £6.6m to £4.8m, largely due to playing 5 home games behind closed doors because of the pandemic. Steady decline since £11.9m peak in 2012, so revenue only mid-table in the Championship, less than half #LUFC £11m.

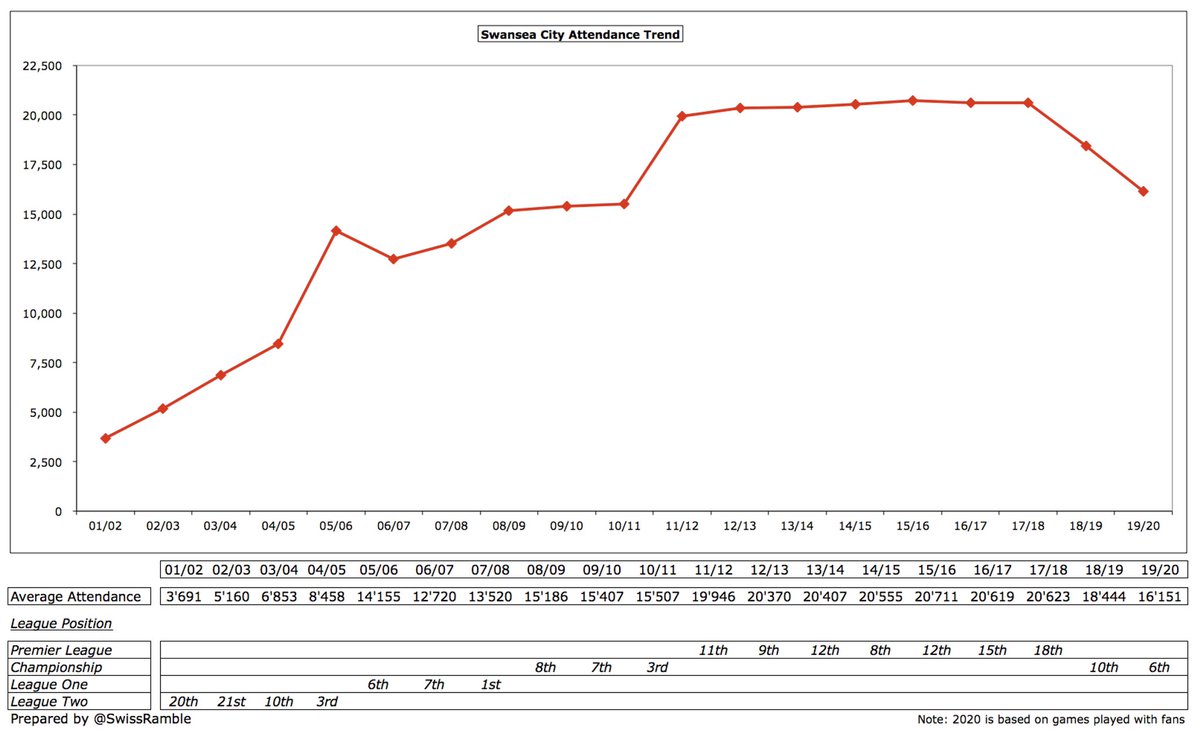

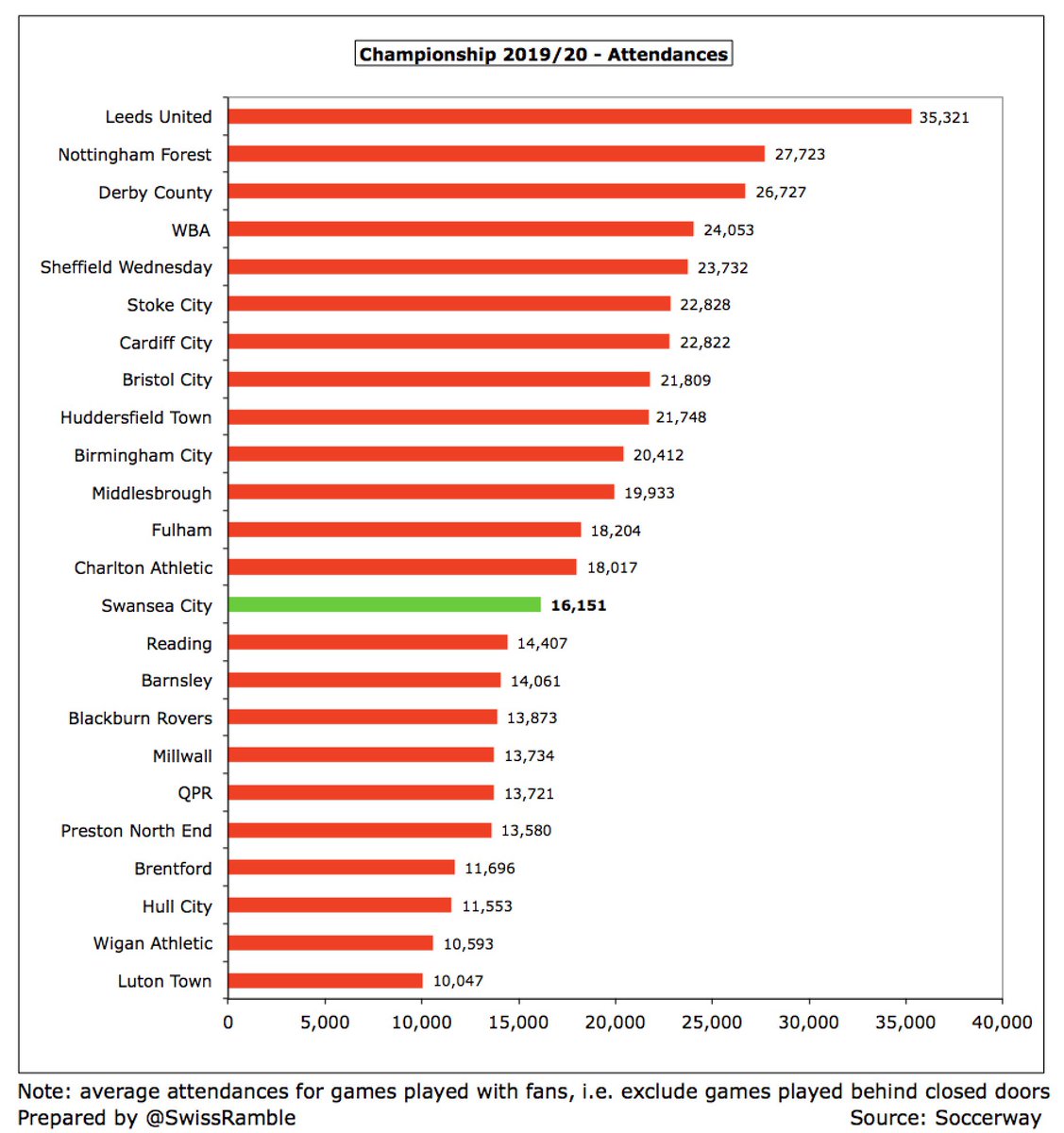

#Swans average attendance (for games played with fans) dropped 12% from 18,444 to 16,151, which is down 4,500 since relegation and now in the bottom half of the Championship. The club has slashed ticket renewal prices for the 2021/22 campaign.

#Swans have bought the land at the south end of the stadium, while acquiring 100% of the company responsible for the Liberty Stadium management. This would facilitate stadium capacity expansion, but this would only be considered after a return to the Premier League.

#Swans commercial revenue fell £2.1m (26%) from £8m to £5.9m, comprising £4.0m commercial income and £1.9m other, the lowest since 2013. This is in the bottom half of the Championship, a long way below the likes of #LUFC £34m and Bristol City £14m.

#Swans had a new shirt sponsor in 2019/20, as YOBET replaced Bet UK, but they have since been succeeded in 2020/21 by a new deal with Swansea University. They also have a long-term kit supplier agreement with Joma.

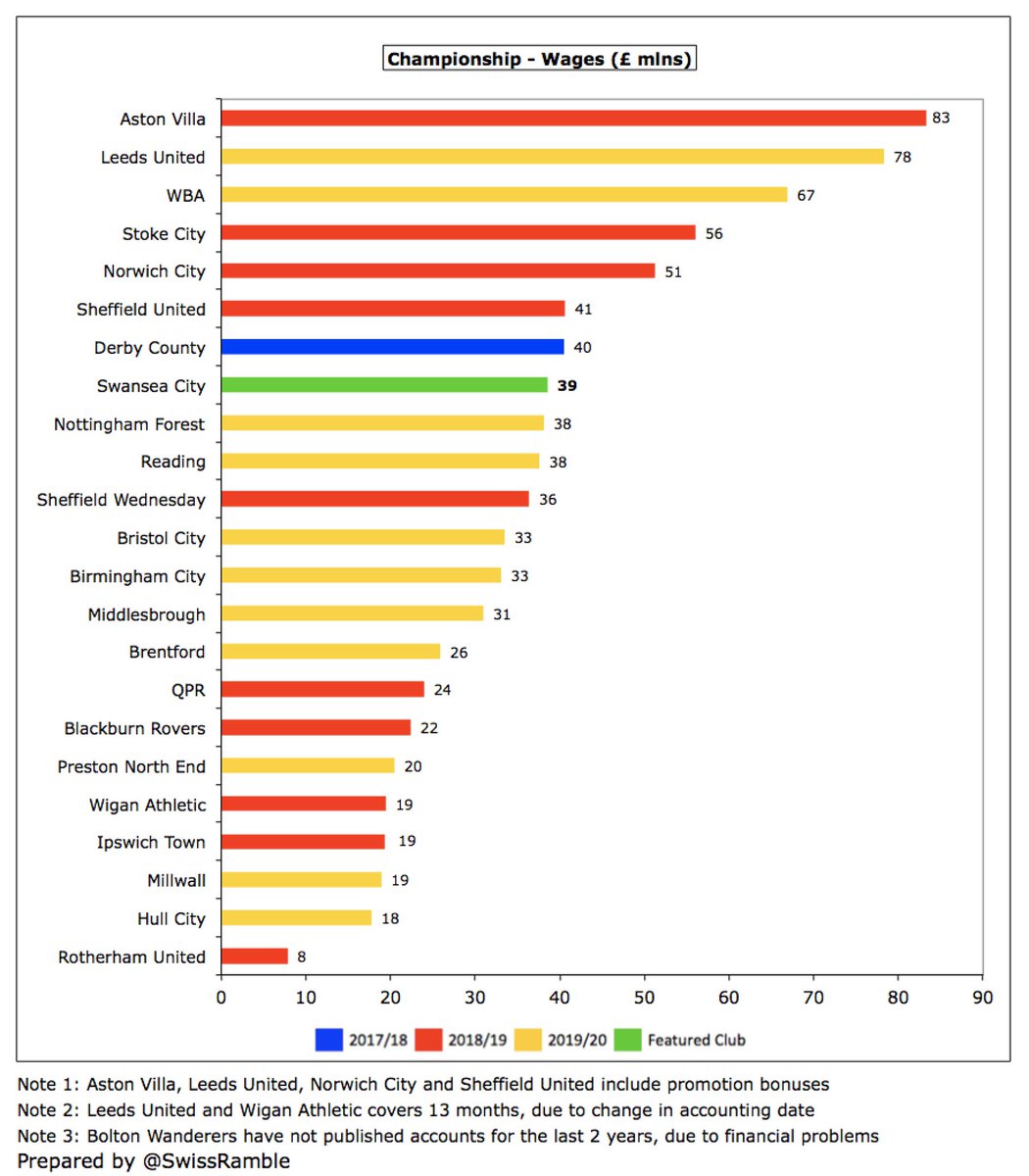

#Swans wage bill fell £9m (19%) from £48m to £39m (excluding £1.7m onerous contracts provision in reported £40.2m), which means wages have been cut £52m (58%) in 2 years since relegation (revenue down £77m in same period). Lowest wage bill since £35m in 2012.

Following the decrease, #Swans £39m wage bill is only just above #NFFC and Reading, both of whom do not benefit from parachute payments. Miles below the likes of #LUFC £78m and WBA £67m, though they included promotion bonuses (estimated at £20m and £16m respectively).

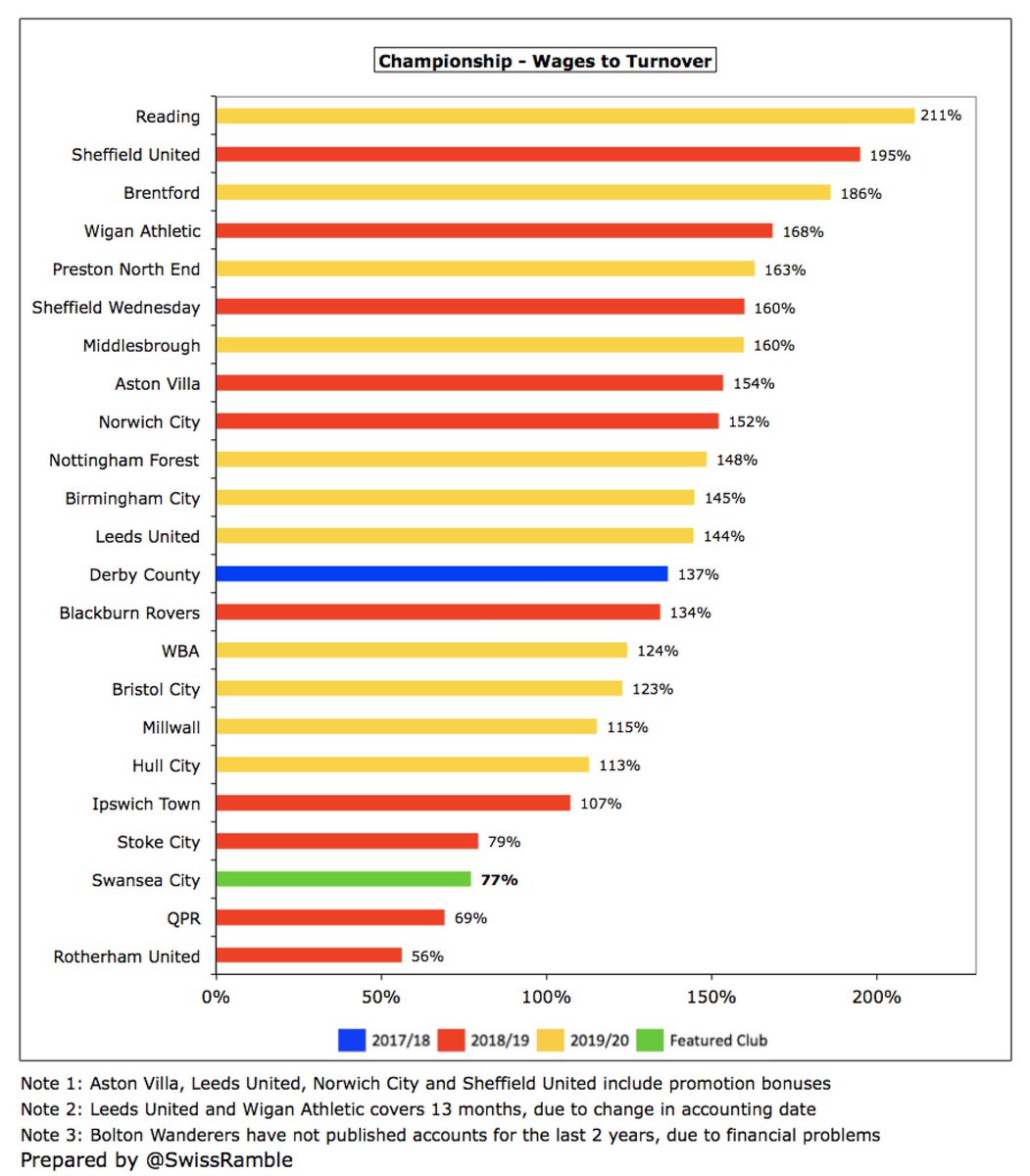

#Swans wages to turnover ratio increased from 70% to 77% (80% including the onerous contracts provision), one of the lowest (best) in the Championship. Incredibly, no fewer than 19 clubs are above 100% with Reading “leading the way” with 211%.

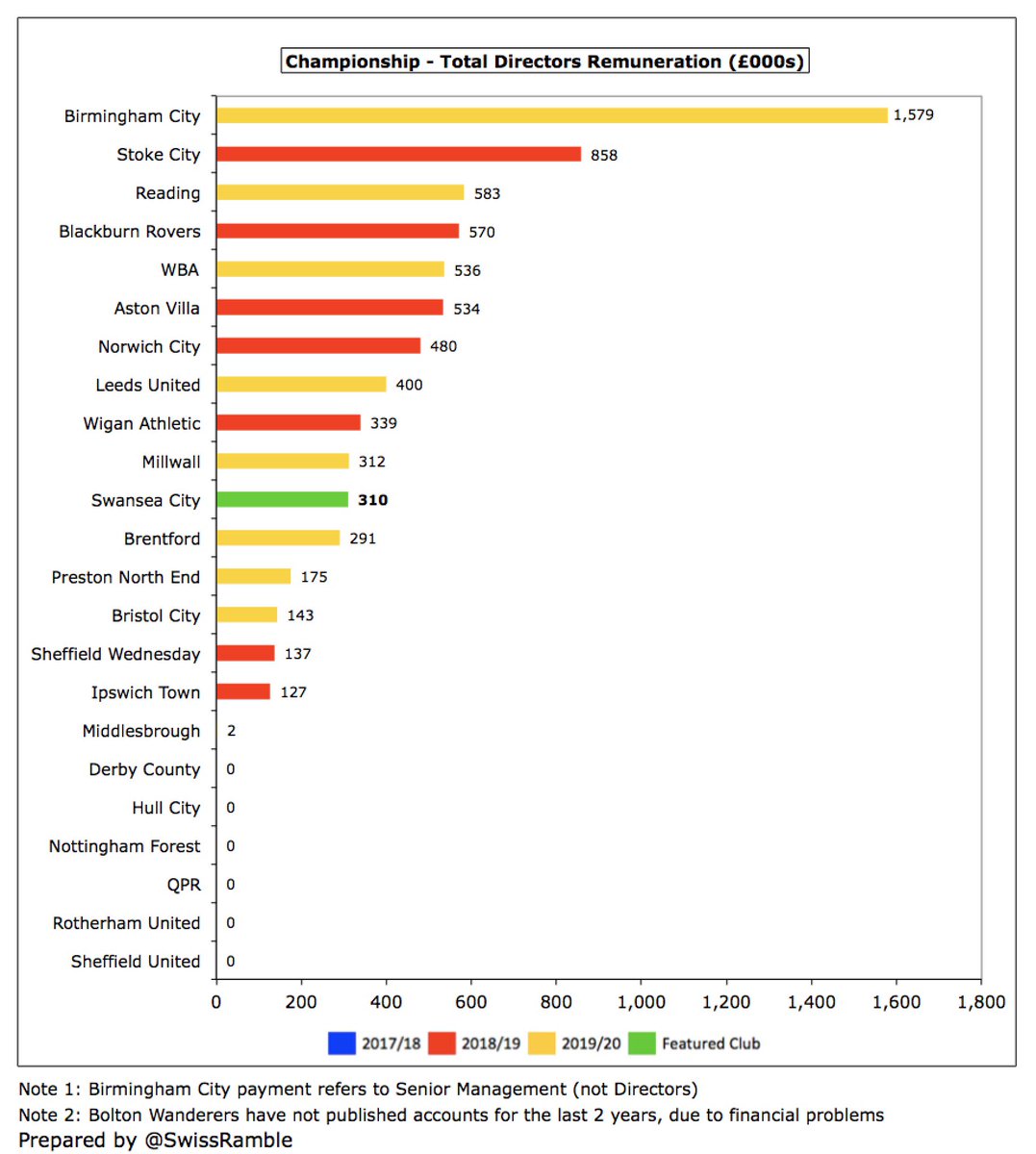

Total remuneration for #Swans directors increased by 27% from £244k to £310k, though this is still on the low side for the Championship. However, it is worth noting that the number of employees was reduced from 359 to 321, down 88 since relegation.

#Swans player amortisation, the annual charge to write-off transfer fees over a player’s contract, fell significantly by £18m (65%) from £28m to £10m, the club’s lowest since 2013. Still fairly high for the Championship, but only half big spenders like WBA £20m and #Boro £18m.

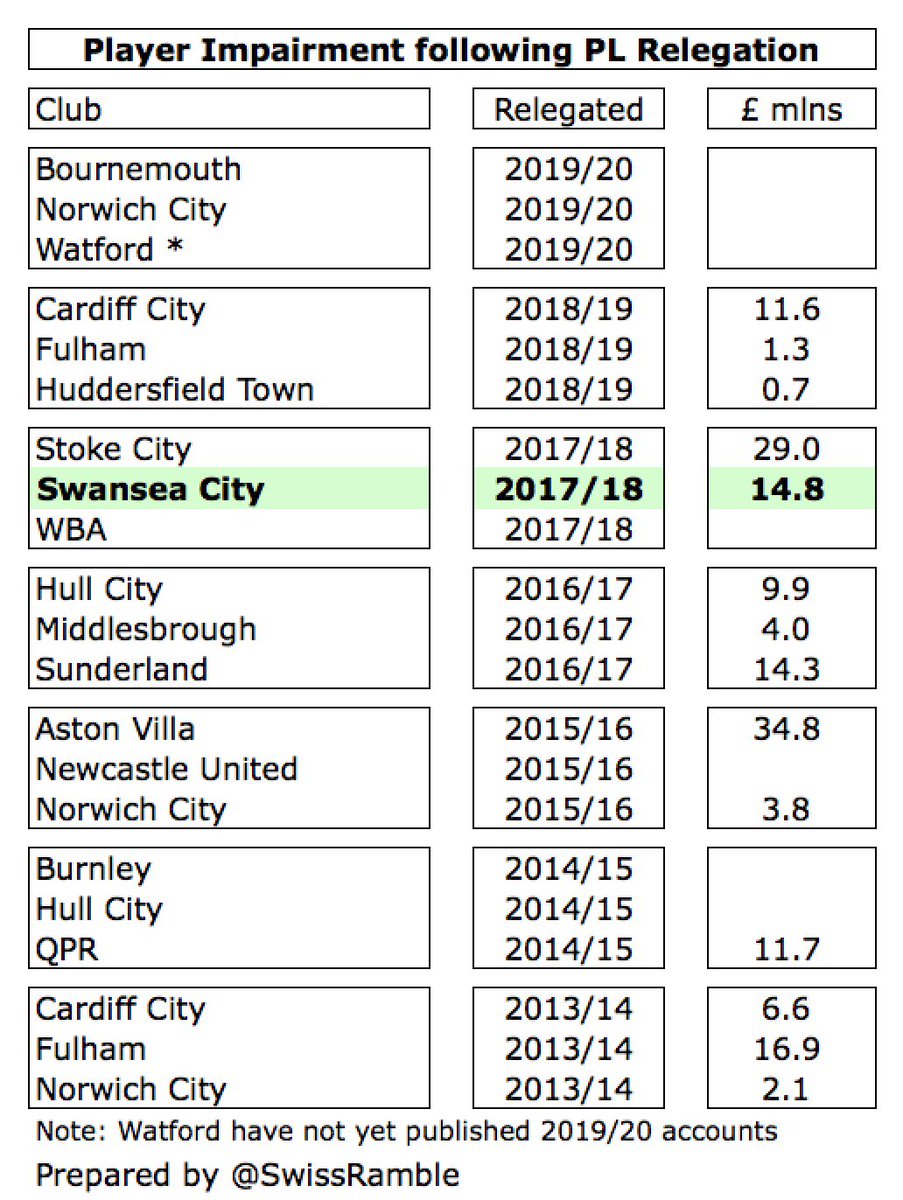

#Swans benefited from booking a £15m impairment charge in 2018. This reduces the value of a player in the books to an amount based on directors’ assessment of achievable sales value and is common practice for clubs relegated to the Championship.

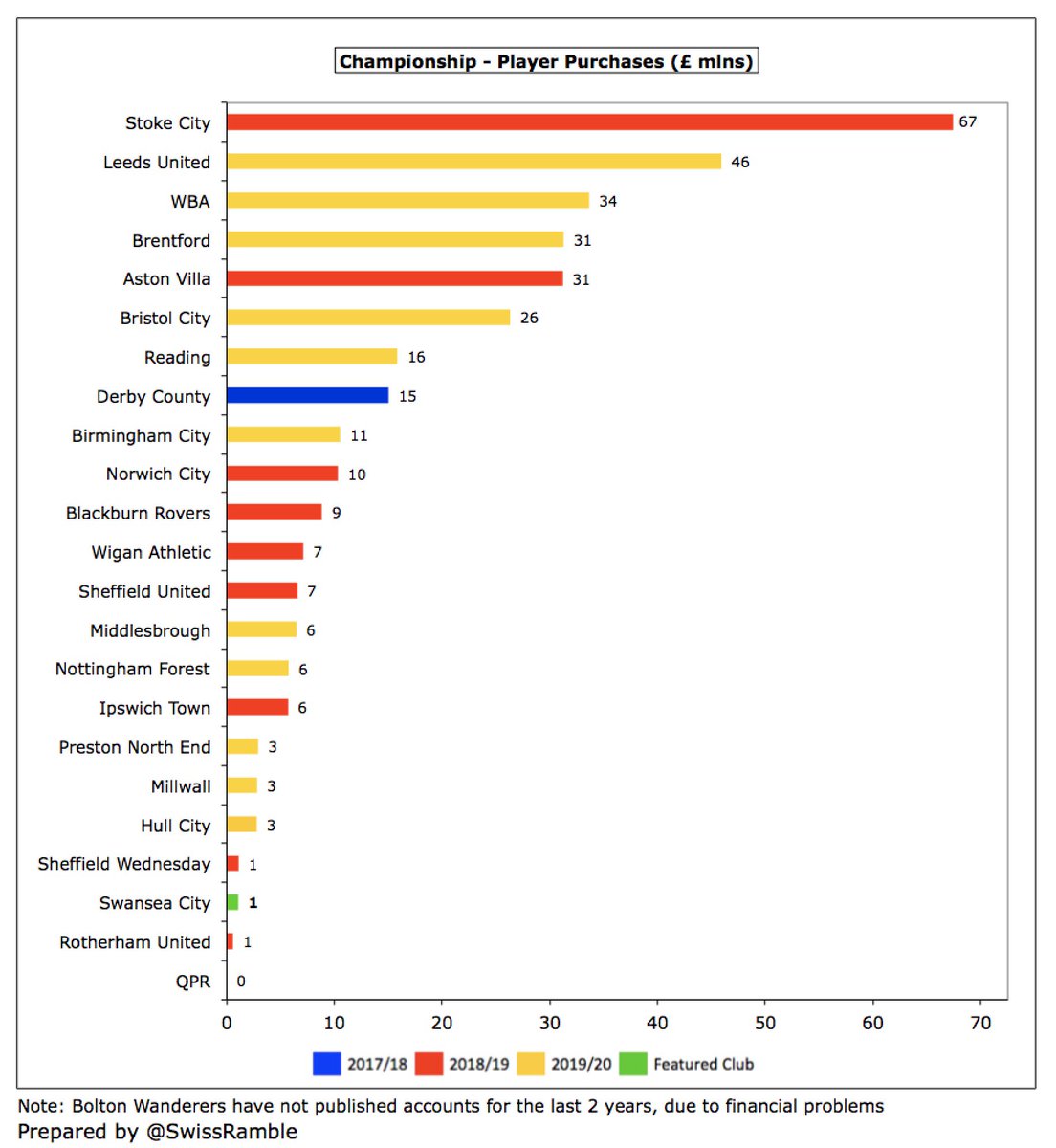

#Swans only spent £1m on player purchases, though they did bring in many loan signings (Woodman, Gallagher, Guehi, Brewster, Kalulu, Wilmot and Surridge). This is the lowest in the 2019/20 Championship to date, miles below #LUFC £46m, WBA £34m, Brentford £31m & Bristol City £26m.

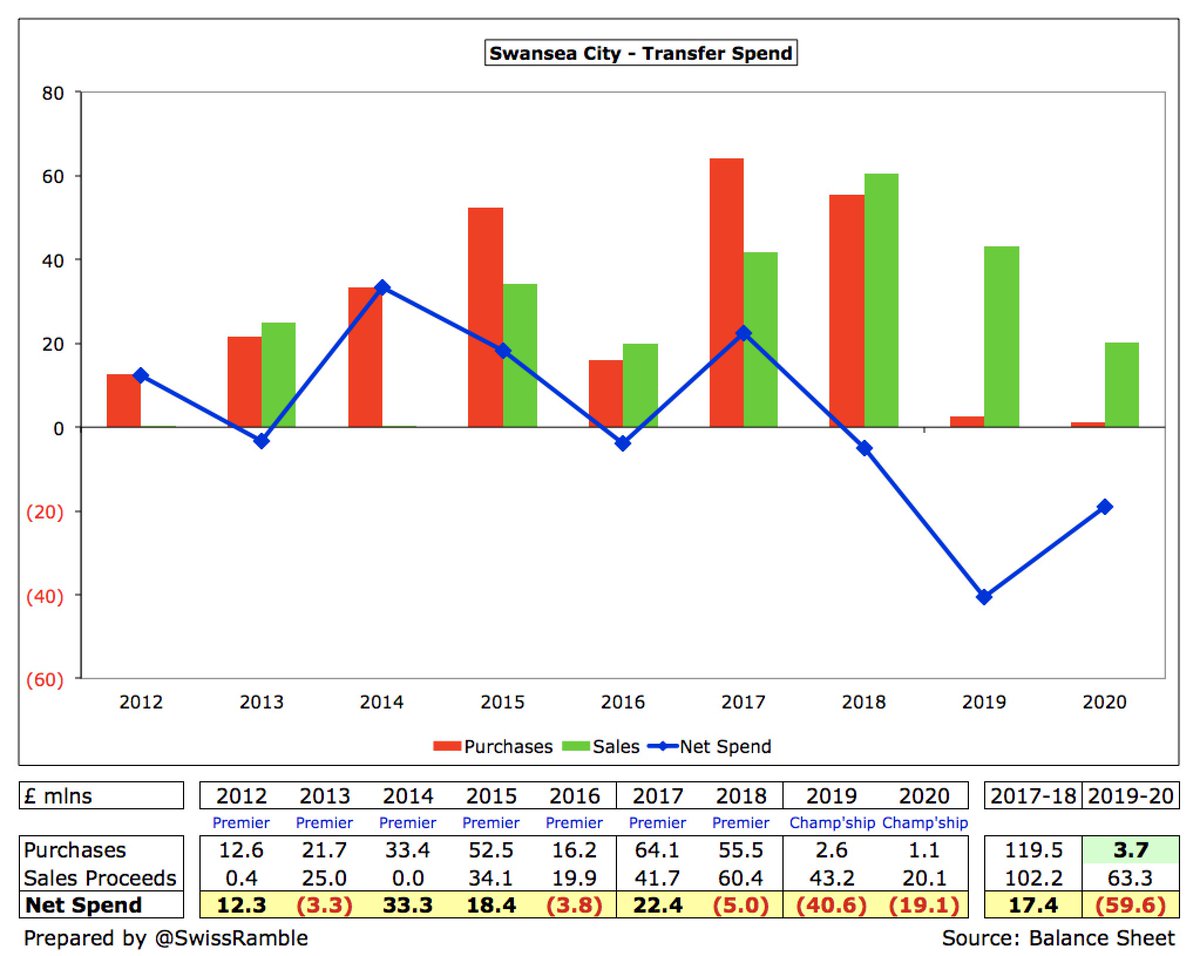

#Swans have spent less than £4m on transfers in the two years since relegation, a huge reduction on the £120m splashed out in the last two seasons in the Premier League (£64m in 2017 and £56m in 2018). It will be much the same this season, as accounts note only £1.6m expenditure.

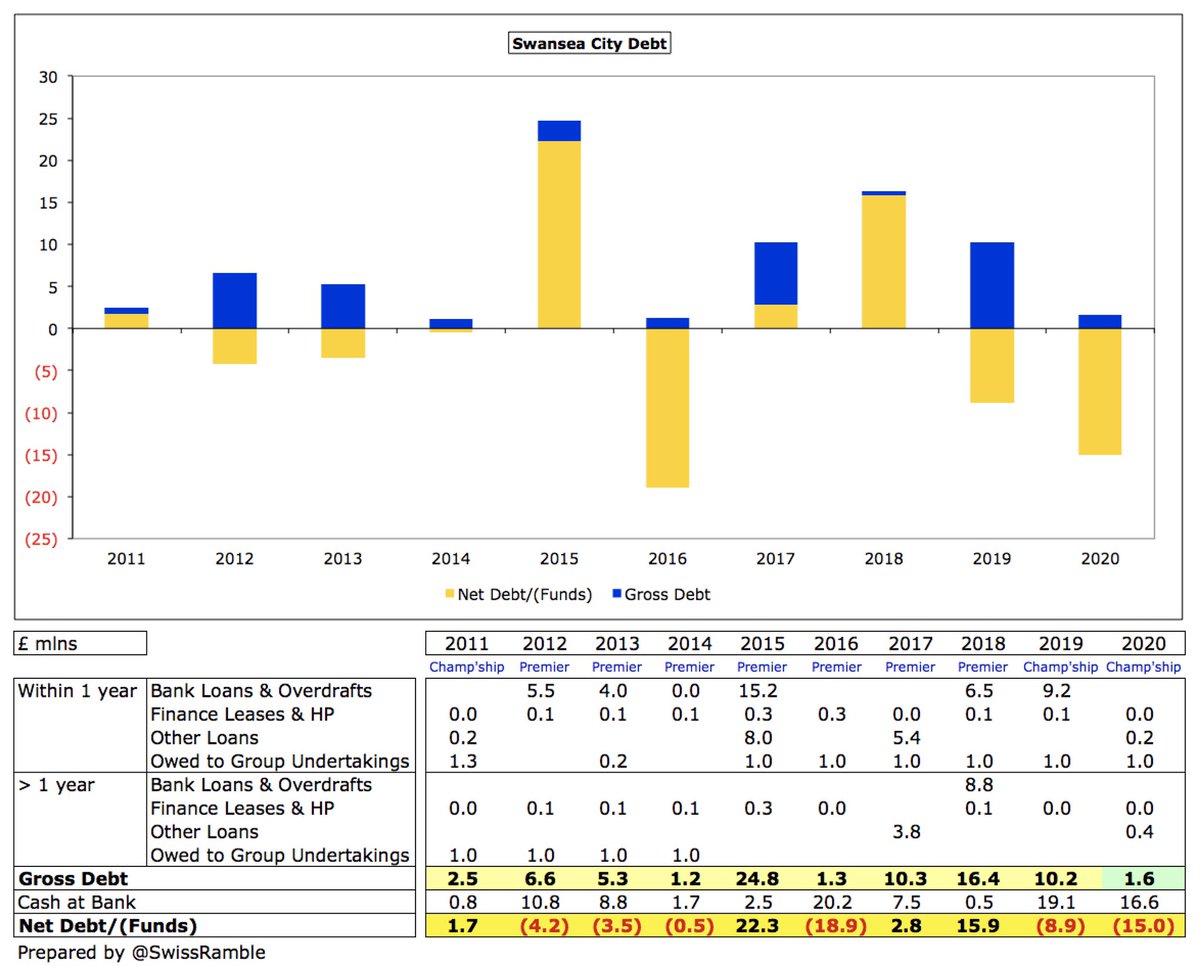

#Swans gross debt fell £8m from £10m to £2m after repaying a £9m bank loan and adding EFL £584k loan. Despite relegation, debt cut from £16m. In September 2020, after these accounts closed, the parent company issued £5m loan notes that may be converted to shares at a later date.

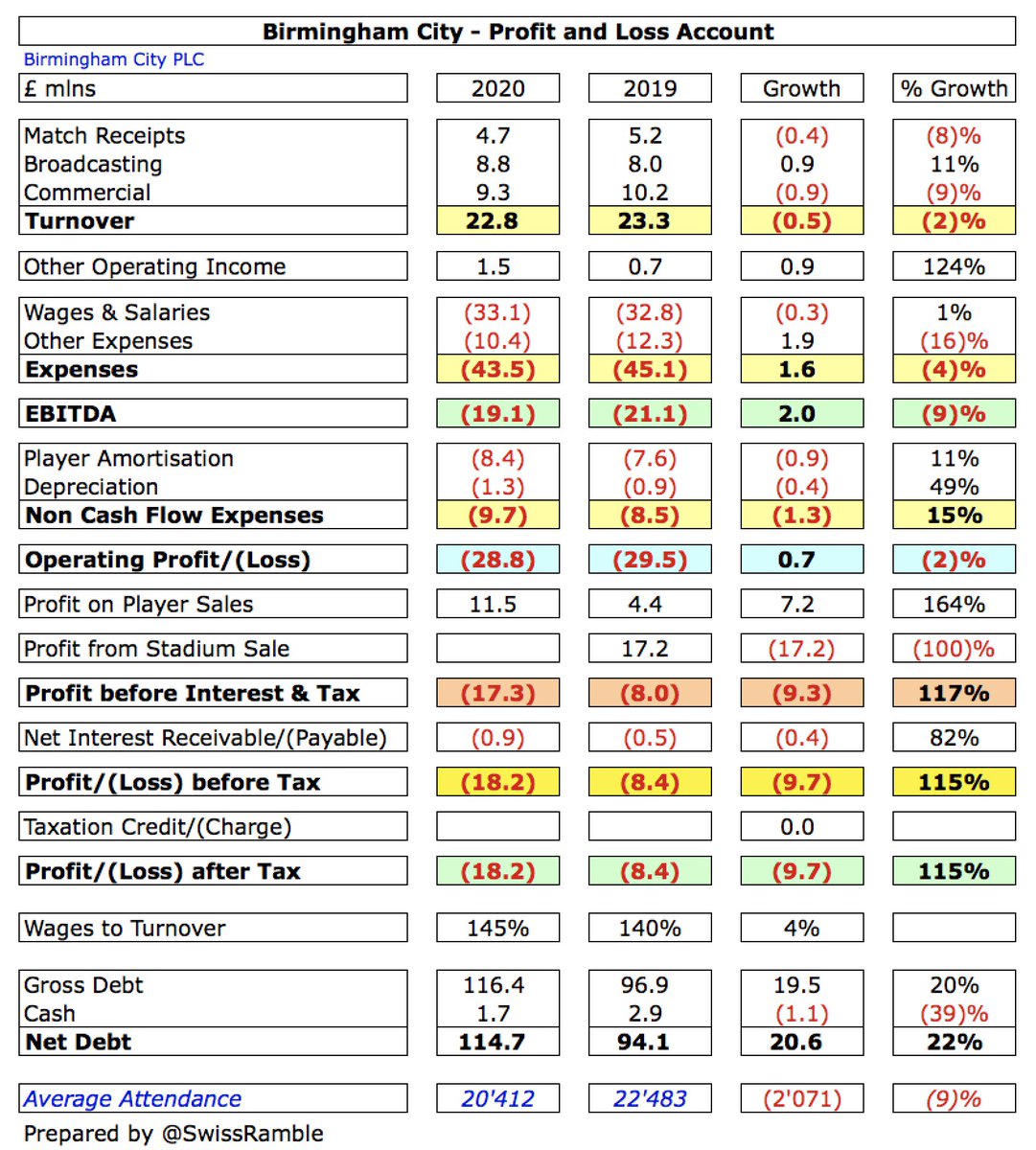

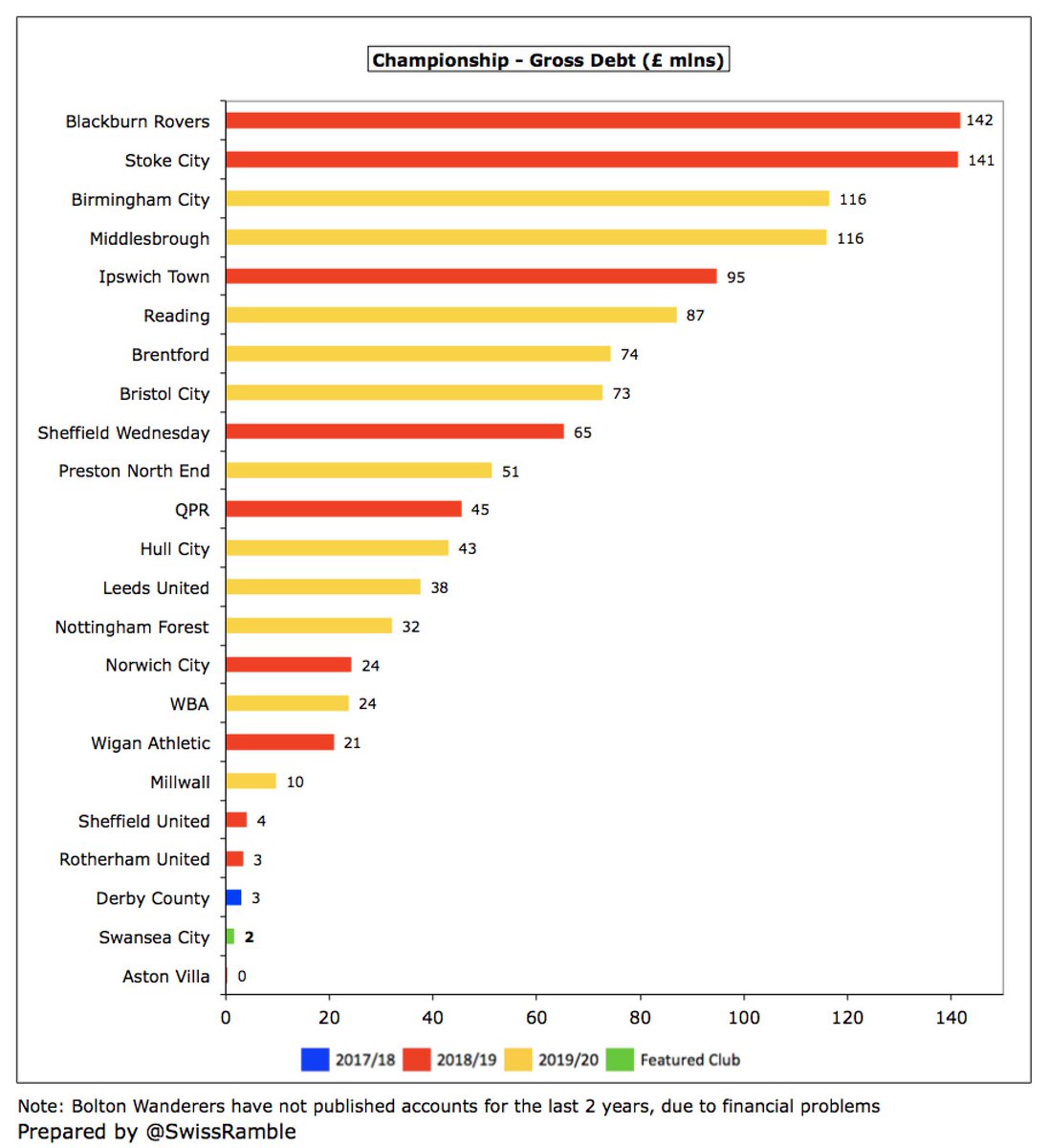

#Swans £1.6m gross debt is the smallest in the Championship, far below the likes of #BRFC £142m, Stoke City £141m, Birmingham City £116m and #Boro £116m. However, almost all debt in this division is provided interest-free by the clubs’ owners, so is “soft” in nature.

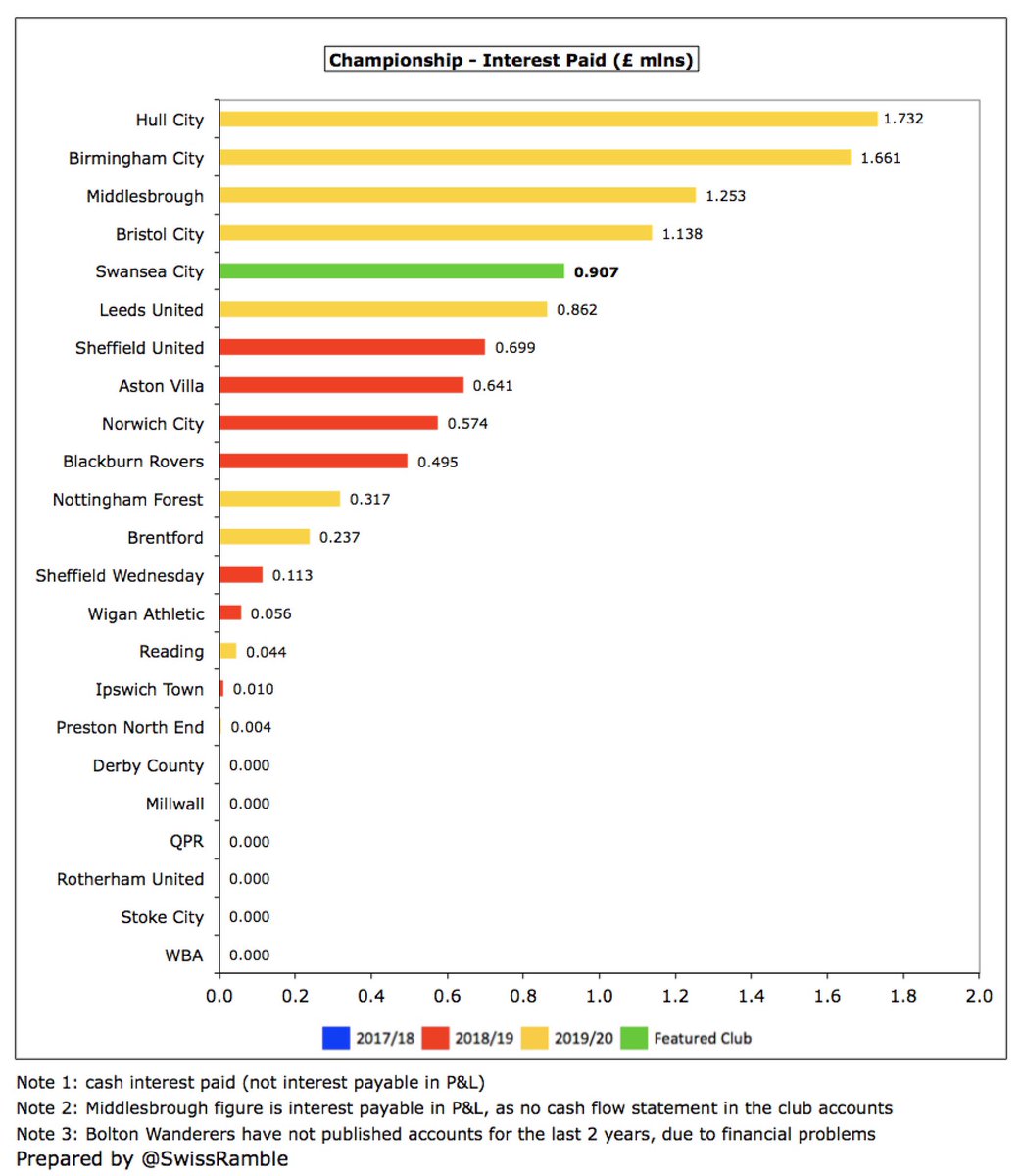

#Swans bank loan charged interest at 4.5% a year with the club paying £907k in 2019/20, which is towards the upper end of the Championship, where much debt is provided interest-free by club owners. Highest payments were at Hull City and Birmingham City, both with £1.7m.

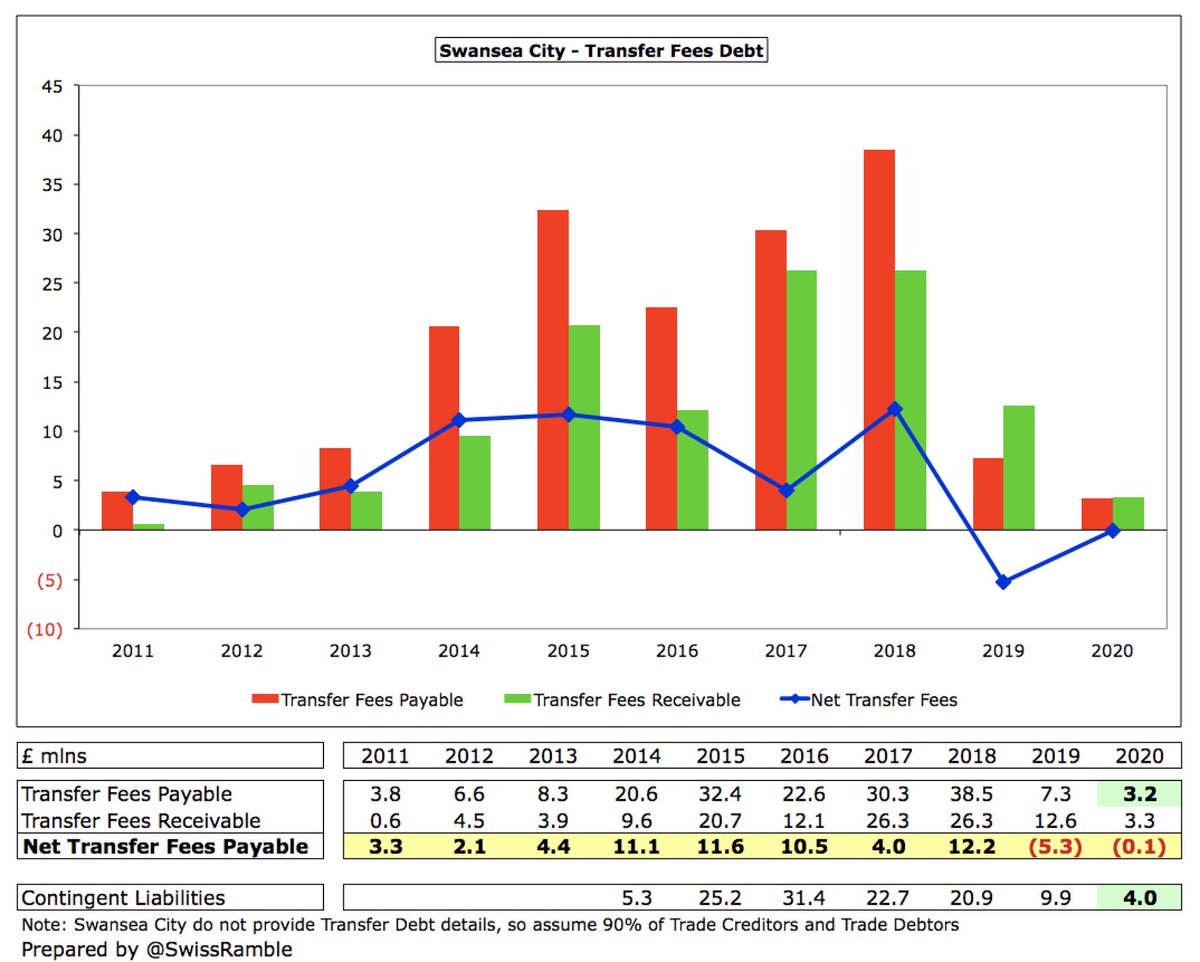

#Swans don’t separately report transfer debt, but assuming 90% of Trade Creditors, this fell from £7m to £3m. Swansea are in turn owed £3m by other clubs, so net receivables are zero. In addition, there are £4m contingent liabilities, dependent on appearances, team success, etc.

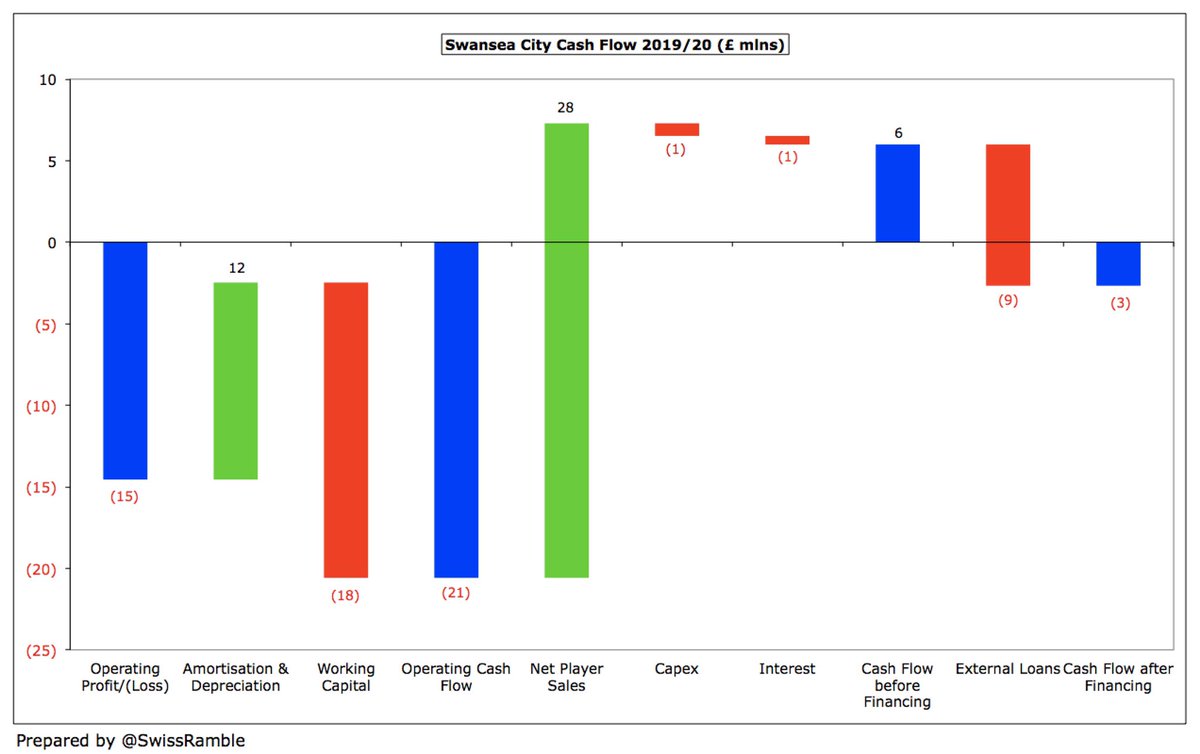

#Swans £15m operating loss improved by adding back £12m amortisation & depreciation, offset by £18m adverse working capital moves, giving £21m negative cash flow. Boosted by £28m net player sales (sales £33m, purchases £5m), but repaid £9m bank loan, giving £3m net cash outflow.

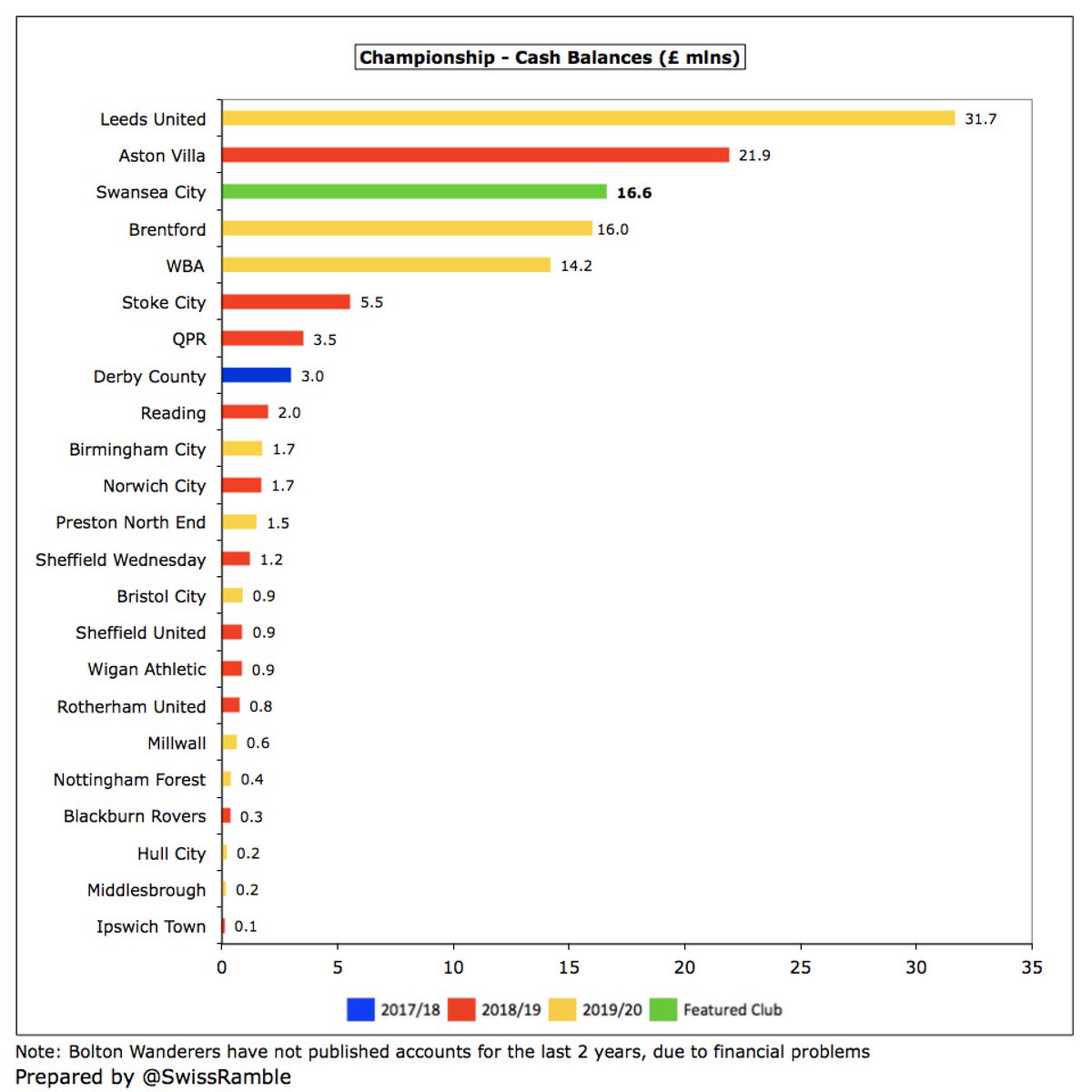

Despite the £3m reduction, #Swans cash balance of £17m was still one of the highest in the Championship, only surpassed by #LUFC £32m. Most Championship clubs had less than £2m cash in the bank, so this was a pretty good buffer in the current economic climate.

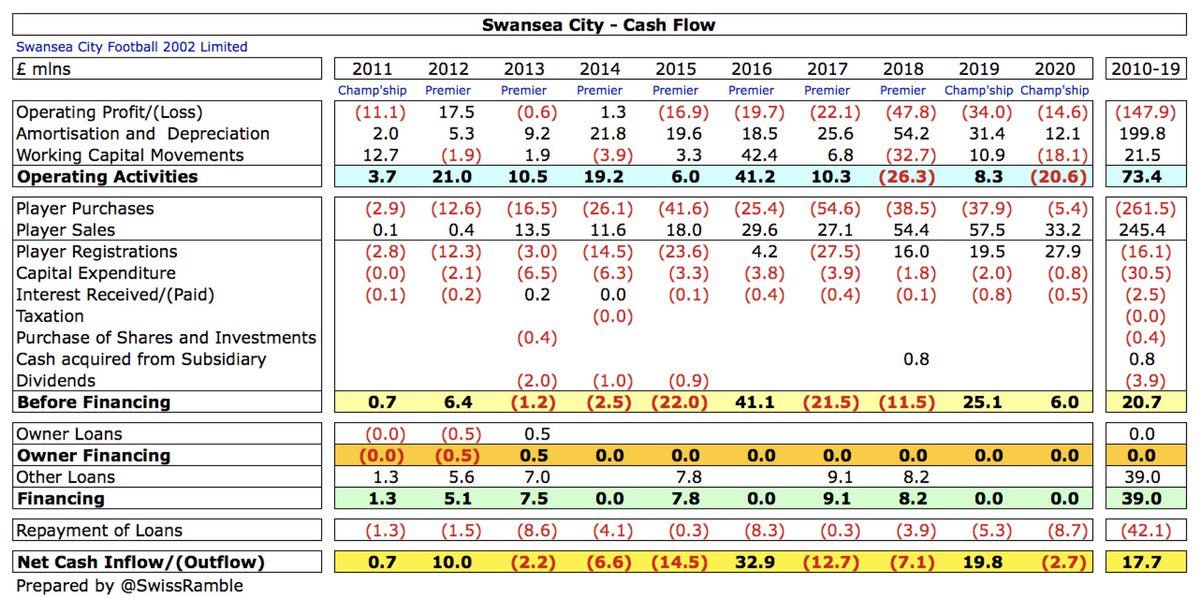

In the last decade #Swans have generated £73m cash from operations. Most has been spent on infrastructure £31m with only £17m on player purchases (net). Another £4m went on dividends, £3m loan repayments and £3m interest. The rest simply increased the cash balance by £18m.

#Swans are now in the fifth season under the control of an American consortium led by Stephen Kaplan and Jason Levien, who bought 68% of the shares. In August 2020 fellow businessman Jake Silverstein also invested in the club, reportedly for a stake of at least 5%.

The owners have only put in £5m loan notes last September. Otherwise, they have been unwilling (or unable) to provide funding with player sales covering any shortfall. The sustainable approach is admirable, but #Swans fans will have noted the club’s decline since their arrival.

#Swans CEO Julian Winter said, “An overall profit on the back of a loss the previous year shows a great deal of progress on the road to being financially stable, but the club is still balancing the tricky conundrum of being competitive on the pitch and prudent off it.”

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh