In his ‘Art of Biblical Narrative’, Robert Alter makes some highly insightful comments about *direct speech* (pp. 83-85).

The OT, he says, tends to avoid indirect speech.

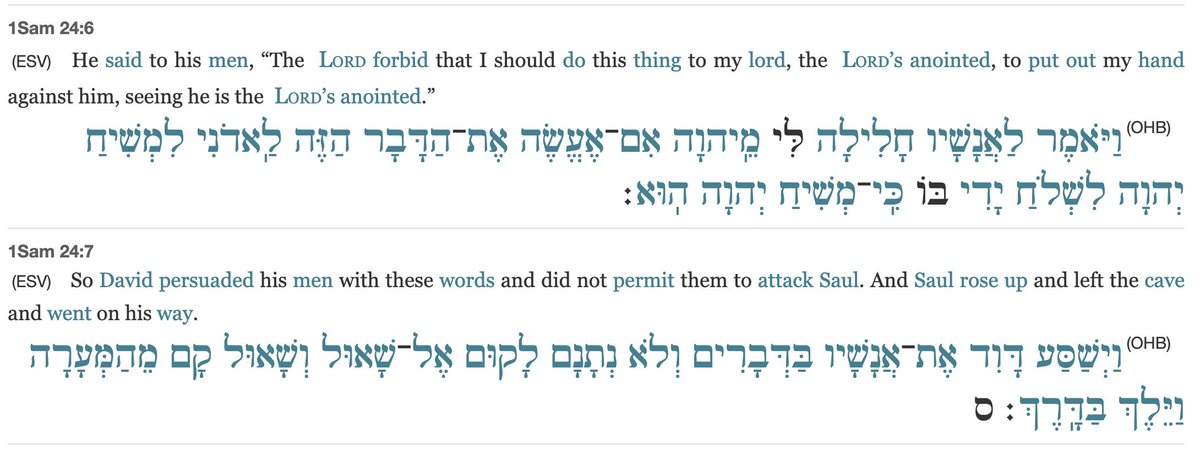

By way of example, Alter discusses the text of 1 Sam. 24, where Saul strays into the cave in which David and his men have decided to hole out.

‘David explained it would be unacceptable/blasphemy to...etc.’

‘David explained he could not possibly...etc.’

But the Biblical text switches to direct discourse.

For one thing, it brings David speech-act into the foreground.

It portrays David as a man who wants to convey the solemn nature of his situation to his troops.

The text makes us feel the urgent presence of David saying,

‘I am the king’s vassal; he is my master; he is God’s own anointed, the sanctity of whose election is an awesome thing.

I will *not*, therefore, do what you and I may present see as a possibility.

The use of direct speech also adds layers of ambiguity and complexity to the narrative.

‘An avowal by David reported in the third person’, Alter says, ‘would inherit the authoritativeness of the narrator’

‘But as things are actually presented in 1 Sam. 24, we find ourselves confronted with David’s speech,

In other words, the text merely tells us what David *says*.

Did a part of David share his men’s sentiments?

Was his statement in 24.6 for *his* benefit as much as his men’s (cp. 24.7)?

Might it even have been meant to function as a kind of oath/commitment?

The reader is thereby encouraged to actively engage with Samuel’s narrative.

which requires 1 Sam. 24 to be viewed not as an isolated incident, but as part of a bigger story.

In Gen. 2, Adam is only told not to *eat* from the tree.

Is that because ch. 2 is non-exhaustive and Eve’s speech in ch. 3 fills out its details?

Or was no such command given in the first place?

Did Adam misreport God’s command to Eve?

Or is Eve’s statement an early example of man’s tendency to put ‘hedges’ around God’s commands?

Further complexity is then created by the Bible’s interconnectedness/intertextuality.

He is old and infirm and constrained in what he is able to do.

As yet, the man in question has not revealed who should inherit his wealth and authority.

He appears to favour his older son,

But, due to the influence of his wife, things turn out differently.

While the older son is away, the man is persauded to bequeathe his inheritance to a younger son instead of the older son,

Whose story is described here?

Jacob and Esau’s, right?

In part.

These events *do* clearly fit the story of Jacob and Esau.

and has not yet revealed who should inherit his wealth and authority. (Or at least so it seems: cf. below.)

David appears to favour his older son, Adonijah,

whom he views as a replacement for his beloved Absalom.

But, while Adonijah is absent from the palace, Bathsheba approaches David and persuades him to bequeathe his inheritance to *Solomon* instead,

which causes Adonijah to ‘tremble’ when he finds out (1.49).

Or do they?

Rebekah and Jacob’s behaviour is clearly deceptive. Can the same be said for Bathsheba’s?

Possibly. It is hard to tell.

1 Kgs. 1’s events are triggered by Adonijah,

In response, Bathsheba and Nathan cook up a plan.

First, Bathsheba enters the king’s presence.

Then, at the appropriate time, Nathan comes in and seconds Bathsheba’s statement,

All well and good, one might say.

But is Bathsheba’s statement about Solomon *true*?

Did David *really* bequeathe his throne to Solomon?

Might Nathan and Bathsheba have convinced him to honour a promise he never actually made?

At first blush, it does not *seem* as if they did,

🔹 We are never actually *told* David bequeathed his throne to Solomon.

The text simply tells us what is *said*.

Whether these statements are true or not sometimes requires careful contemplation.

First, the sophistication of the Biblical narrative is quite remarkable.

The Bible is a book which invites and repays careful thought. When it is read in a careful (& sympathetic) manner, it actively engages the reader and draws him/her into its world.

We may not immediately be able to identify that purpose (and/or may never identify it), but we should continue to look for it.

== THE END ==