But the opposite is often true. Police can be remarkably uncritical.

Case in point: Scientific Content Analysis.

1/

We had never heard of SCAN. We wanted to know more about it.

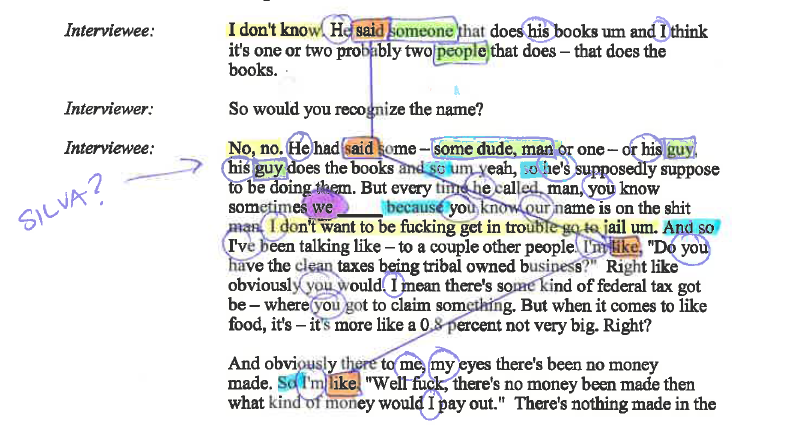

Here’s a real-life sample, from an investigation conducted by the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife.

But does SCAN work?

These researchers found that in separating fact from fiction, SCAN was about as effective as flipping a coin.

We bought some.

Its first page says the FBI opened an investigation “into whether individuals associated with the Trump Campaign were coordinating with the Russian government…”

“Please note,” Sapir writes: “The report says, ‘whether…’ and not ‘whether or not…’”

To grammarians, the use of “or not” in that sentence would be redundant and therefore poor writing.

To Sapir, the words’ absence reveals intent.

Sapir counts 14 instances in the 290-page book in which Comey describes the opening or closing of a door, be it to a garage, office or minivan.

On a local-access TV show, Sapir analyzed Hill’s Senate testimony in the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings.

Hill said: “I had a normal social life with other men outside of the office.”

“Oh, oh my goodness,” the interviewer said.

propublica.org/article/why-ar…

A task force comprising the FBI, CIA and the U.S. Department of Defense wrote in a 2016 report that SCAN “is widely employed in spite of a lack of supporting research.”

In other words, the very agencies that cite SCAN’s lack of scientific support.

Through public-records requests, we obtained documents from 40.

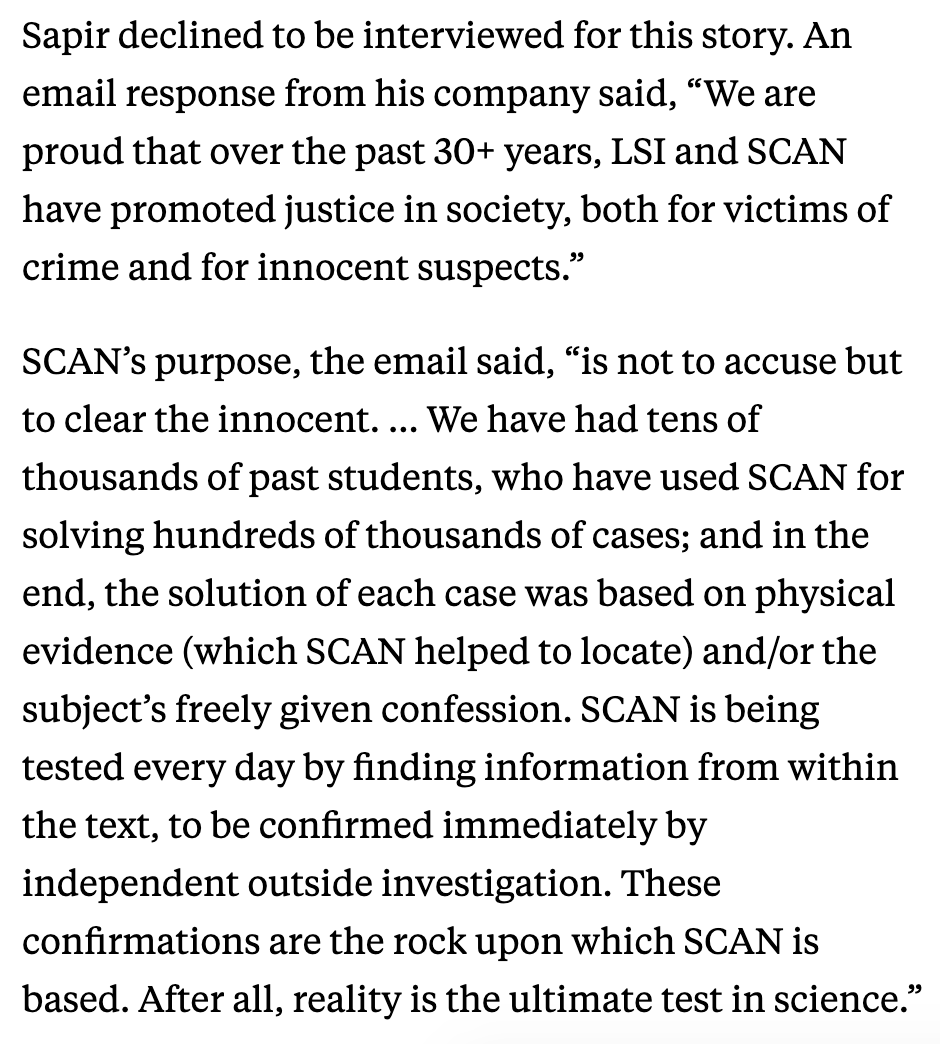

This year, there were two more waves. Seven Rangers received the training in Austin. A week later, 10 more attended the course in Kingsville. Here’s what they said when I asked them about it:

In an email to other Rangers, he said he had received the training himself. He wrote of Sapir, “He is a true master at detecting deception, and his technique is way better than a polygraph.”

Bloodstain-pattern analysis: bit.ly/2OcJXzr

Photo analysis: bit.ly/2OaLHce