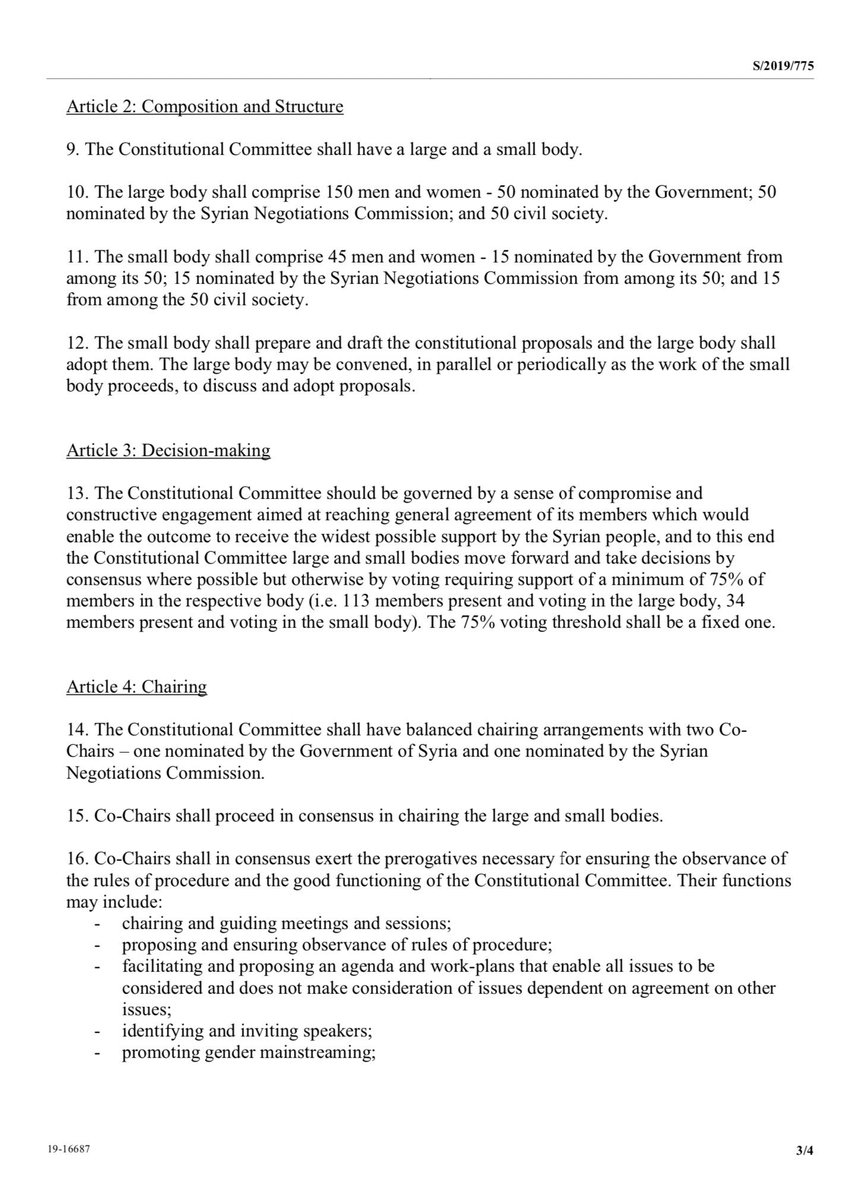

Thread with quotes from the book

"In 1808, the government built Fort Dearborn on a small hill near the shore of a large freshwater late. The soldiers defended the fur trade. Chicago was built, literally, for trading."

amazon.com/Futures-Specul…

"Merchants started arranging to sell in advance. On March 13, 1851, a seller promised to deliver corn the following June for 1¢/bushel less than the March price."

"The traditional futures market, because of its written and cultural limits, serves as useful example for how markets ought to work." (inside flap)

"So traders provided insurance: by locking in prices in advance, they took risks that other people didn't want." (p. 7)

Consistent with Lambert, they find that contracts that may not have functioned well as insurance (extreme returns or easily substituted) were less likely to survive.

"Finally, the secretary of agriculture demanded that Board of Trade members oust the clique of

"Because the clearing firm was on the hook, it watched the trader. If he looked like a wild gambler, the clearing firm limited how much he could trade." (p. 14)

"A new trader had to learn not to talk about how much he had made or lost.

"The Merc tried to get the onion ban reversed.... Many onion growers now hated the traders. Without growers, and people who wanted to hedge, they didn't have a viable market. The traders dropped their court battle.

"This seasonal problem created a trading opportunity." (p. 47)

"It was getting tougher for businesspeople to budget because they didn't know how far the dollar would go in the near future.

"In 1971, Nixon tore up the Bretton Woods system." (p.79)

"The pit was like a candy store. All bankers needed to do was use forward contracts to buy British pounds from customers...

"But the bankers lacked the risk-taking soul of traders using their own money. The bankers traded only a tiny amount of futures (if they traded at all)." (p. 84)

"They could make a few thousand dollars a day, practically risk-free. Eventually, the bankers would instruct their own men to trade." (p. 85)

"The experience made him confident—even more so than before—that currency futures would work. The traders in the pit offered better deals than the banks themselves were willing to give." (p. 86)

"Traders had to make sense of formulas and equations that looked like alien scribbles." (p. 103)

"The trade who could quickly do the calculations in his head had an advantage and probably got the trade." (p. 103)

"The traders in Chicago seemed to always offer better prices than the ones in New York did." (p. 106)

"Sandor watched the market change. In the boom, thrifts couldn't keep up with the loans people wanted.

"Bomar's goal was to take those loans in batches of,

"But while he waited to sell the loans, Freddie was exposed to interest rate risk. Bomar wrote an article expressing a wish for a futures contract as a hedge." (p. 114)

"Back then, if a person wanted to buy or sell a Ginnie Mae, he called a dealer who would quote a price. Cahnman stopped by the Chicago office

"Cahnman realized they were in the same business and believed he could rival the mortgage-dealing professionals. He had no office space to maintain or fancy furniture to buy.

"But Ginnie Mae was just a stepping-stone to the pit that would change the Board." (p.123)

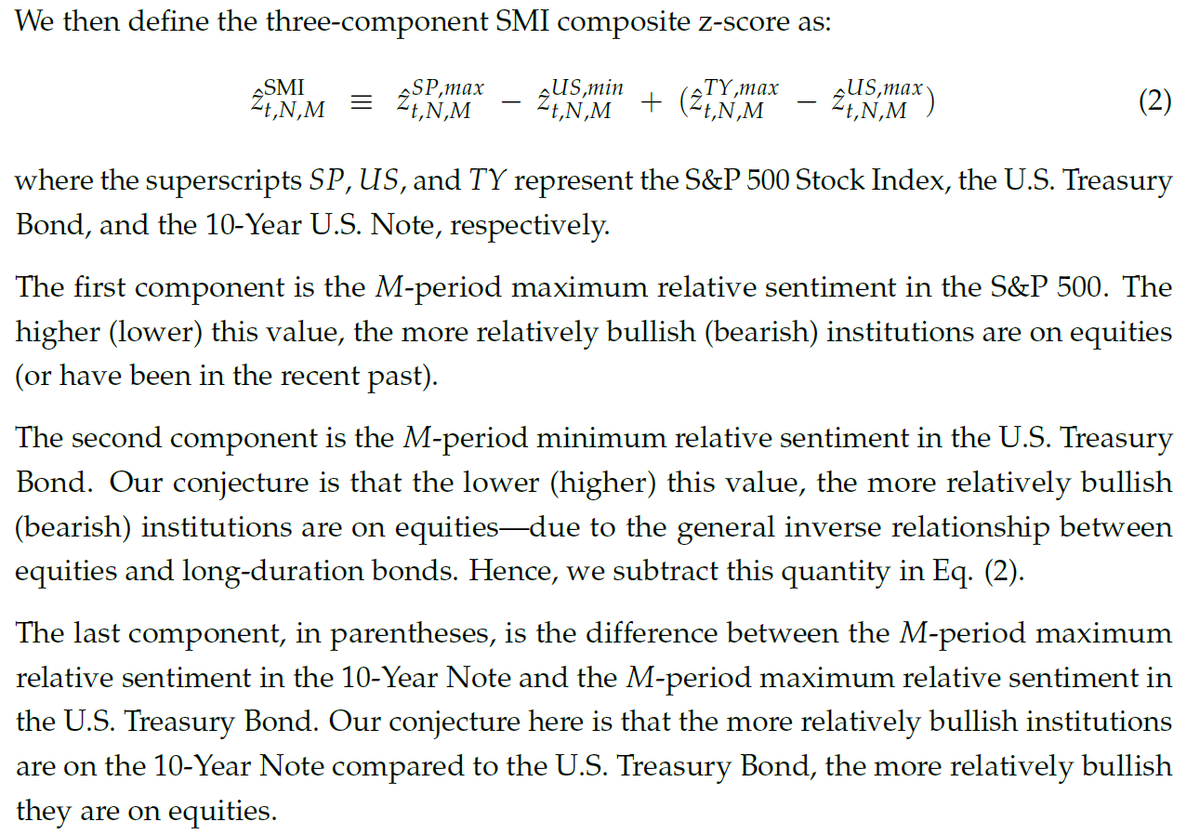

Time Series Momentum

(Trend following for stocks)

Trends Everywhere

"Salomon traders, led by Meriwether, saw a way to make some easy money.

"Then came 'Tall Paul.' Volcker called an unusual weekend press conference and announced some moves intended to slow inflation (partly by raising interest rates). Overnight, the bond business went berserk.

"It became more acceptable to trade futures. Banks set up desks on the floor. Bonds brought Wall Street to Chicago." (p. 133)

"The new exchange didn't have hundreds of people willing to risk their own money and trade against major institutions." (p. 134)

"The same could apply to stocks. Millions of investors owned stocks and worried about prices falling. Pension fund managers worried about prices rising before they had a chance to buy." (p. 140)

"The era of the egg men was officially over, and the new era of the modern speculator was racing forward." (p. 148)

"The names of clearing firms were blacked out, but

"The clearinghouse had a 7:30 AM deadline. If it didn't receive funds by that point, the exchange couldn't open.

"A futures trader was in a public marketplace where everyone saw his trade. In the clearinghouse, a scorekeeper knew who the biggest

"Swaps didn't need a public marketplace or a clearing firm or a clearinghouse, things that were in place to prevent manipulation and to direct speculative impulses." (p. 174)

"Electronic trading threatened this way of life, particularly for floor brokers." (p.181)

"A few months later, traders on the floor could tell something was changing. Soon the pit was empty, an open wound on the trading floor. The computer won." (p. 187)

"In the 1970s, the chief executive of Freddie Mac had fretted that pools of mortgages could lose value. Three decades later, in the frenzied market, they did.

"Some banks that had made loans collapsed with the housing market. Some companies that had used swaps to provide insurance on mortgages collapsed or nearly did.

"The year looked like a referendum on free markets and on capitalism itself. But there was a better test case:

"They left blueprints showing how a group of people constructed markets that, on balance, worked well." (p. 201)

"He is happiest close to his ranch and cattle business. For him, the business is still about animals and the people who trade them. It always was." (p. 206)