Let's talk about Dreyfus' critique of AI! (Megathread)

Searle's arguments were bad and wrong and that's all I have to say about that.

Dreyfus' arguments were slightly better, but they're old and they don't really apply to the AI boom today.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubert_Dr…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AI_winter

@FrankPasquale mentioned Dreyfus in his keynote @ #AIES2020

IF (whistling) THEN (no chewing)

Symbol manipulation isn't sufficient for embodied phenomenology.

Two questions we'll come back to: Why think symbolic processing can't reconstruct this knowledge? More importantly: Why don't computers have bodies?!?!

Then Seymour Papert asked Dreyfus to play chess against an MIT computer, and Dreyfus lost.

In 1997, IBM's Deep Blue beat Kasparov, and Dreyfus had to again walk back his claims.

dl.tufts.edu/concern/pdfs/s…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_Blue…

And yet despite the obvious counter-examples, the popularity of Dreyfus' critiques of AI persist. What's going on?

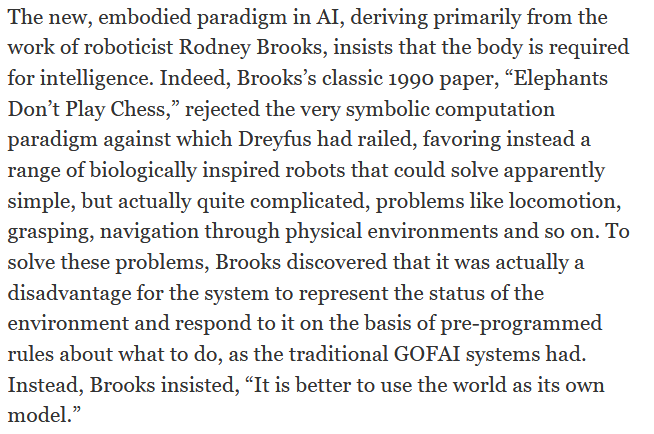

1) Dreyfus' critique of GOFAI was good, actually... and AI/Robotics listened and changed!

2) A long tradition of tech/science skepticism in continental philosophy

3) That generation of AI skeptics finally have something to say!

Modern AI techniques (evolutionary algorithms, neural networks, etc) aren't vulnerable to Dreyfus' arguments.

Haugeland was a major influence on Dreyfus' interpretation of Heidegger.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Haug…

plato.stanford.edu/entries/embodi…

Atlas can do flips because it is an embodied dynamical system.

opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/02/28/wat…

The critique is an anachronism.

bit.ly/2v0Bb0j

bit.ly/2P9WuDw

Insofar as 4E theorists want a theory of mind compatible with the natural sciences, they should probably reject the Jonasian dichotomy between humans and machines.

Dreyfus' arguments do nothing of the sort. They have no obvious application to a modern context of dynamical, learning, socially embedded AI.

Symbolic systems are useful, and they're still widely used!

Again, Dreyfus' critiques are an anachronism.

Not that Dreyfus' critiques have much merit and purchase in the current AI landscape...

And today, in a new golden age of AI, there's plenty of money to pay people to dust off and trot out this old training.

Dreyfus' critique of "computers" mostly targets the giant mainframes in expensive research labs in the 60s.

Cell phones are CLEARLY embodied agents.

cf Haraway: "Our machines are disturbingly lively and we ourselves frighteningly inert."

Every machine has a body too.

If a machine is active,

SET embodiment flags to 'True'...