Authoritarian regimes don't have to worry about anti-authoritarianism being framed in authoritarian language.

He said the mind became blurred by the emotional power of this concept.

That is not a point I think anyone reading this book needs to be convinced of.

The US seems to embrace what he calls managerial culture, where how much say you have has to do with how much you "earn" it.

So clearly we aren't being effectively propagandized, right?

You sew distrust in the reformers, not the idea of reform.

THAT'S propaganda.

They aren't against female protagonists, so long as it's organic; just don't cast women for POLITICAL reasons!

But then they assume every woman is cast for political reasons.

The greatest good in a oligarchy is wealth; the greatest good in a democracy is freedom.

Stanley argues the greatest good in a managerial society is efficiency.

A managerial society cannot be a democratic society.

This is the value of controlling the conversation.

Thanks, folks. We'll be back for more chapters in future.

In a democracy, any legal citizen can gain political power, which a demagogue will and will likely be good at.

Ditto that a failed aristocracy was an oligarchy.

This... places a lot of faith in people.

Honor respect is acknowledging a person holding a position that, by definition, only a few people can have; this person receives deferential respect that not everyone can be given.

Honor respect is inherently undemocratic.

This, he says, is how democracy dies.

He compares the hatespeech laws of the US and Canada to the relative lack thereof in Hungary.

That's a lot to dump in my lap without much resolution!

See you next time, folks.

Epistemic authority is expertise, where your opinion in a certain field is deemed more valuable than a layperson's.

Practical authority is being able to tell others what they can and can't do.

The writers of this report were sociology and government professors.

Stanley claims this conflation undermines the epistemic ideals of both sociology and government.

That's (part of) Stanley's definition of propaganda.

1. A claim must be false to be propaganda.

2. A claim must be made insincerely to be propaganda.

Stanley rejects both.

Klemperer asked his friend how he could support a party which considered Klemperer not a real German:

Sound familiar?

The danger in a liberal democracy is that propaganda will no be recognized as propaganda.

This is what Stanley calls the classical sense of propaganda.

This differs from the classical sense because it is not always in service of an actionable goal.

Stanley feels both the classical definition of propaganda and the "biased speech" definition are too rough to describe the kind he's interested in, though both will be, at times, relevant.

The kind of propaganda that interests him is the kind that exploits an ideal.

Political propaganda is "a kind of speech that fundamentally involves political, economic, aesthetic, or rational ideals, mobilized for a political purpose."

Authoritarian propaganda that glorifies the state is propaganda in keeping with the ideals of that state.

Calling the war in Iraq "Operation Iraqi Freedom" is an example.

People who could not vote were overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic.

This is not only undermining propaganda. This is in service of an unworthy ideal.

They traffic in conclusions, not arguments.

Even if Bernanke's hope was to communicate the urgency of the situation, his word choice left people even more mislead about how the economy operates.

Because it cloaks an erosion of public understanding in the guise of educating the public, it is antidemocratic propaganda.

Stanley argued that pretty much any conception of democracy idealizes public reason.

Therefore, propaganda can be expected to frame itself as an embodiment of public reason.

"Practical rationality impartialism" is not a phrase that rolls off the tongue.

But good god, you gotta try.

A democracy is "reasonable" inasmuch as it can account for the needs of all the people its policies will affect.

This is *rational* from the position of self-interest, but it is not *reasonable* because it doesn't respect the needs of the neighbors.

There's no real mechanism for people who are disallowed from being part of the debate to get their needs met.

"You should be using the system as it already exists."

A democracy can't admit that it's not fully democratic already.

Stanley's final paragraph legit begins "In this chapter, I have explained..." and then summarizes his main points. He also writes thesis sentences at the beginnings.

These are 40-page hamburger essays.

JASON STANLEY I'M NOT HERE TO GRADE YOUR DISSERTATION I JUST WANNA READ ABOUT PROPAGANDA

Most arguments against the Klan aren't that we should deny them their rights, but that we should deny them the power to deny others their rights.

But I also get wary of anyone who attributes that misogyny to porn at large and not the mainstream porn industry in specific.

I'm down for any dissection of the semantics of porn that acknowledges most of the problems with porn are problems with capitalism.

1. the speech codifies a group as unworthy

2. separate from that codification, the speech aims to legitimately resolve another debate

3. mere use of this speech, in any context, undermines reasonableness

This manner of speech could be used by people on any side of any debate; even by all sides.

This book would be half as long if he didn't repeat himself.

"I am the President of the United States" is a true statement if Obama says it in 2014.

It's untrue if Obama says it in 2005, or if someone else says it in 2014.

The person you're talking to may like you romantically, platonically, or be feigning interest.

These can't all be true, but any could be true.

This new info enters the common ground for evaluating future assertions.

"Which way is the gas station?" is in the common ground as a question that needs answering.

If you didn't see the gas station yet, then it's possible you missed it, but it's more likely to be ahead than behind.

"Birds fly" is a generic statement that makes us more inclined to rank "this specific bird can fly" higher than "this specific bird is flightless" until new information comes in.

The subject - what is at-issue - is that you stayed with your grandma. Further discussion will be about that. Where she lived is not-at-issue. It's supplemental information.

"It must be raining outside."

The "must" adds the not-at-issue content that the rain has not been observed, only inferred. This is VERY hard to argue with.

If someone's just babbling to fill the silence and hasn't actually inferred anything, language doesn't have a smooth mechanism for that.

This, again, is very hard to debate. Stanley likens it to the "must" in "in must be raining."

This is the demagogic speech Stanley hypothesized earlier.

They refuse to recognize racism that is in any way smuggled into another conversation, even when it's not particularly well-hidden.

But the only image of racism they conceive of is of racists who talk about race. If it's not overt, how could it be racism?

There is an at-issue fact that is, in theory, factual and morally neutral (there are Jewish Americans), but there is a not-at-issue argument that this is in some way wrong.

The not-at-issue content is less an argument than a set of emotional responses and associations.

Let's see if we can finish this chapter. #IanLivetweetsHisResearch

Often statements delivered by people with power over you are commands disguised as conversation.

And people don't only rank scenarios by likelihood, but also by preference.

The imperative cloaked as a statement and the not-at-issue content that sneaks into the common ground without debate.

We think of slurs as being about either insulting the group the slur refers to or expressing contempt for that group to others of your own group.

This can span the whole gamut from ignoring their perspective in democratic deliberation, or being more comfortable committing genocide against them.

A rite of passage for Hutu boys was decapitating snakes, so "snake" became a slur for Tutsis when Hutus began murdering them.

But political speech often uses words that have the same PROPERTIES as slurs.

I'll say that again: CODED RACISM INCREASES RACIAL BIAS MORE THAN EXPLICIT RACISM.

But using the terms of that debate, they euphemistically denigrate themselves.

Which means if you point out that the language is racist, people will often turn on YOU because YOU'RE the one who made racism explicit.

People are pressured to simply accept the stereotyped language, or even make efforts to personally distance themselves from the stereotype.

It is easy to ban slurs. It is very hard to ban language that has the same connotative effect as slurs.

How do you ban a word that has many connotations and is only propaganda in certain contexts?

How do you prevent propagandists from simply picking another word?

How would such a law NOT get abused?

It's an issue I've seen on a lot of forums. If a moderator details a code of behavior, you inevitably get trolls using the code to "prove" that good-faith actors are bad-faith actors.

It's all very obviously bullshit, but it's nigh-impossible to write a framework that *proves* it's bullshit.

I don't think Stanley has even once used a metaphor in the entire 177 pages I've read.

Like I said, it reads like a dissertation.

His answer: flawed ideologies are the result of flawed social structures.

We interpret the world in such a way that we are already moral in it, and what we were going to do already is in the best interest of everyone.

Aristotle pointed out that there are two causes of revolution: People believe themselves to be equal but are treated as lesser, or people believe themselves to be superior but are treated as equal (or lesser).

They will believe slaves are violent, and will be a threat to society if not controlled.

They will believe slaves are primitive, and unable to govern themselves.

And once they are believed, they will encourage further violence.

Thanks for joining me, my lovelies.

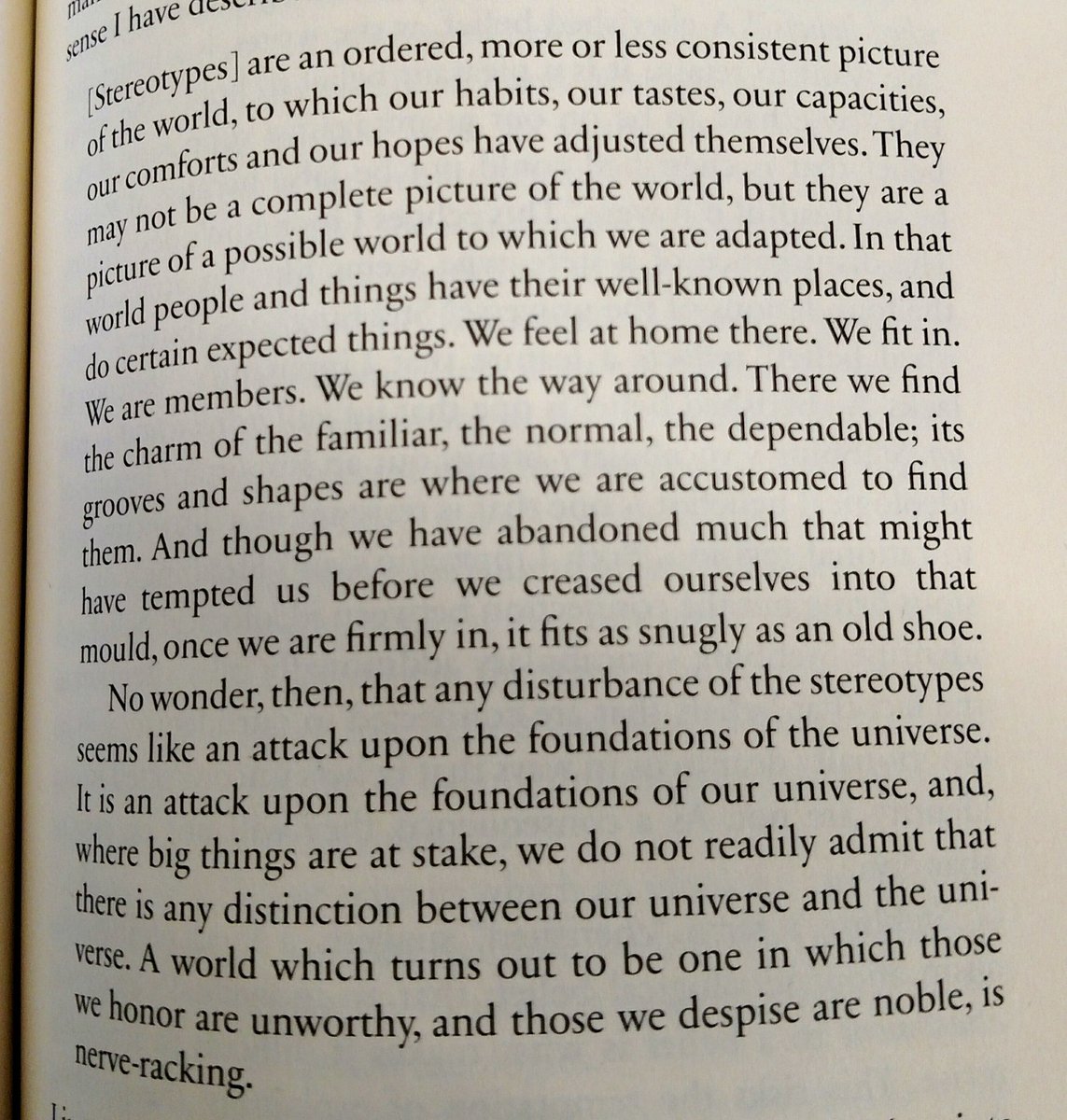

This was central to my Why Are You So Angry videos: people get very emotionally invested in certain worldviews.

He says what makes a belief cherished is less that you're *emotionally* invested and more that you're *sociologically* invested.

These belief is foundational to your day to day life and to your community.

A person who believes stereotypes about Black people is unlikely to have much contact with Black people, and therefore won't have those stereotypes challenged by lived experience.

Did you know people will more often MISrecognize hand tools as guns on Black people than on white people?

But the purpose is to help you determine the truth of the world efficiently.

There are only two chapters left. Christ, I hope I get through them quickly.

#IanLivetweetsHisResearch

He is going to argue that inequality is fundamentally antidemocratic.

Social structures will lead both into flawed ideologies.

This is true even when they have more by inheritance or pure chance.

I can't tell if Stanley is mentioning it or if he's going to actually share the data at some point, so I'm logging it here for future reference just in case.

Stanley argues, however, that stark material inequality will inevitably lead to political inequality.

That's not a revelatory concept, I'm just noting the term for posterity.

Reasoning that specifically aims to keep you aligned with a group is "identity protective cognition."

This kind of groupthink pushes us away from that, and will make us far more susceptible to demagoguery.

What leads OPPRESSED people to embraced antidemocratic ideals?

Or you just have more money than your neighbors, even if that's very little money in the grand scheme.

This means almost everyone has SOME investment in the status quo.

Stanley rejects the idea that we get to decide what we believe.

People generally believe what they are raised to believe.

You don't just snap your fingers and believe something different.

...buddy...

...this is not new information.

I know far too many people haven't taken Progressivism 101 but I have!!!

I can't

I fucking can't

hermeneutical injustice

interest-relativity of knowledge

epistemic confidence condition

How Propaganda Works is the book the Far Right wants us to write.

Oppressed people often have their oppression systematically obscured from them.

For you to change that belief, you will need greater-than-average evidence to convince people, but will have lesser-than-average access to evidence.

Basically, if you believe things about the world that are untrue, you don't have full autonomy over your life.

There is one chapter and a short conclusion left. Combined they are about half the length of the chapter I just finished.

We're almost done. #IanLivetweetsHisResearch

They will believe they have power because of merit.

If we believe merit is so unequally distributed between humans, who embrace a system that claims everyone's voice should be represented?

This comes down to how an individual person answers this question: Why don't I have more?

If they believe America is a meritocracy, the obvious answer would be, "I don't have more because I don't deserve more."

The injustice lies with the ones in power.

The system is fine. The problem is where you've been placed in the system. That's the injustice.

Just not you.

It's not because the Elites have too much, it's because the UNWORTHY have too much.

The idea that feminism is about giving power to women who don't deserve it, that equal opportunity is about giving jobs to Black people who haven't earned them.

It must be that the SJWs put their hands on the scales.

Their art is degenerate, their writing is improper, their argumentation is weak, etc.

"All men (sic) are intellectuals, one could therefore say, but not all men (sic) have the function of intellectuals."

The workers should train in practical skills, and intellectual class should be trained for "knowledge work."

This redefinition of efficiency as a democratic ideal is the underlying thesis of our education system.

Lynne Cheney argued as much when she was head of the NEH.

That's... alarming.

I will grab a new book from the library today or tomorrow and hope to high heaven is is better written.