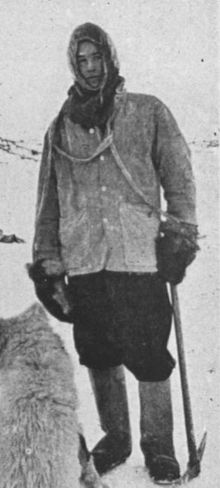

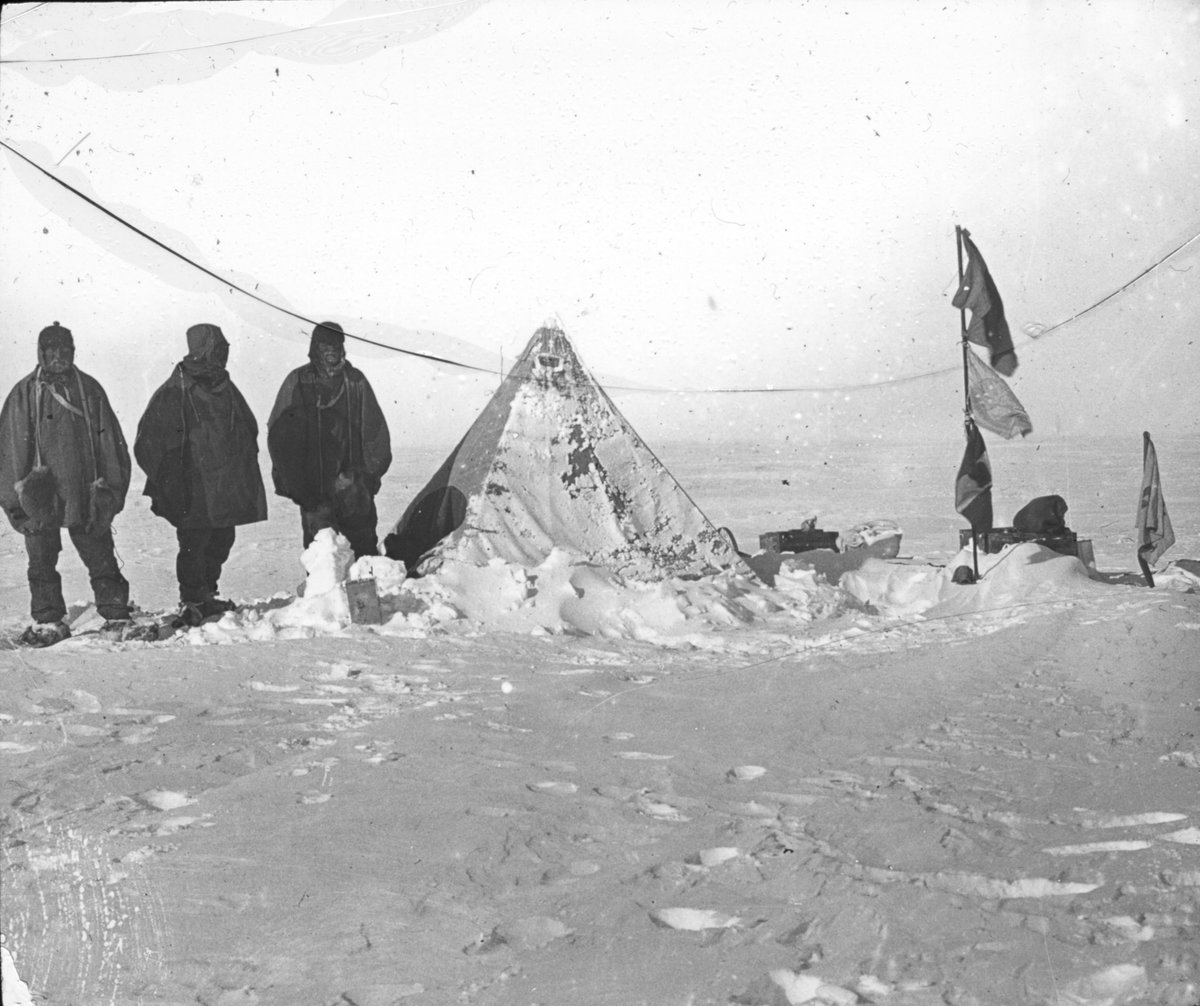

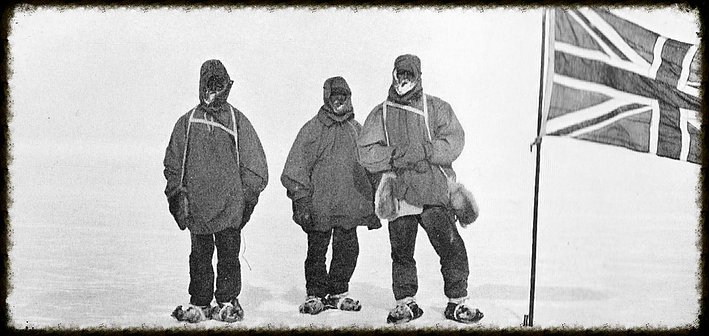

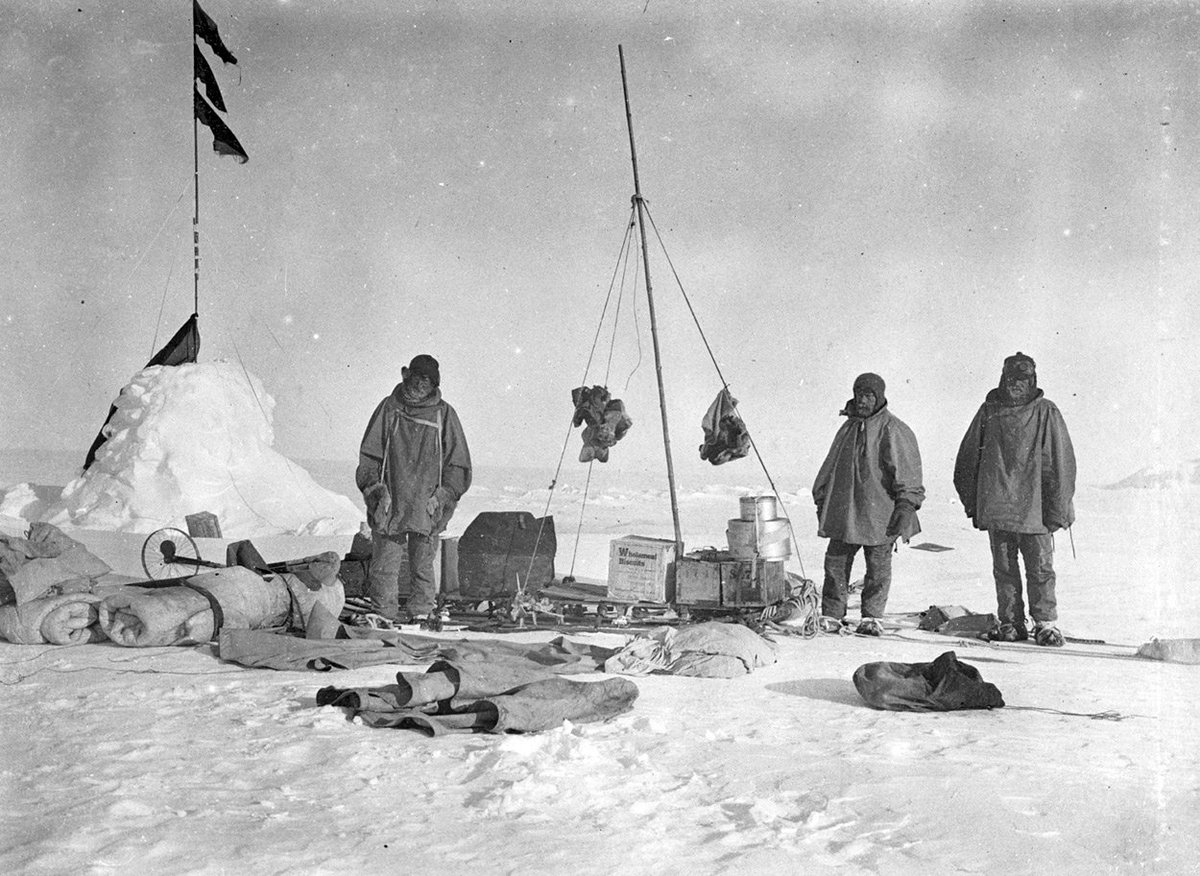

From left to right: Adams, Wild, Shackleton at the Furthest South at 88 degrees 23' S. on 9 Jannuary 1909.

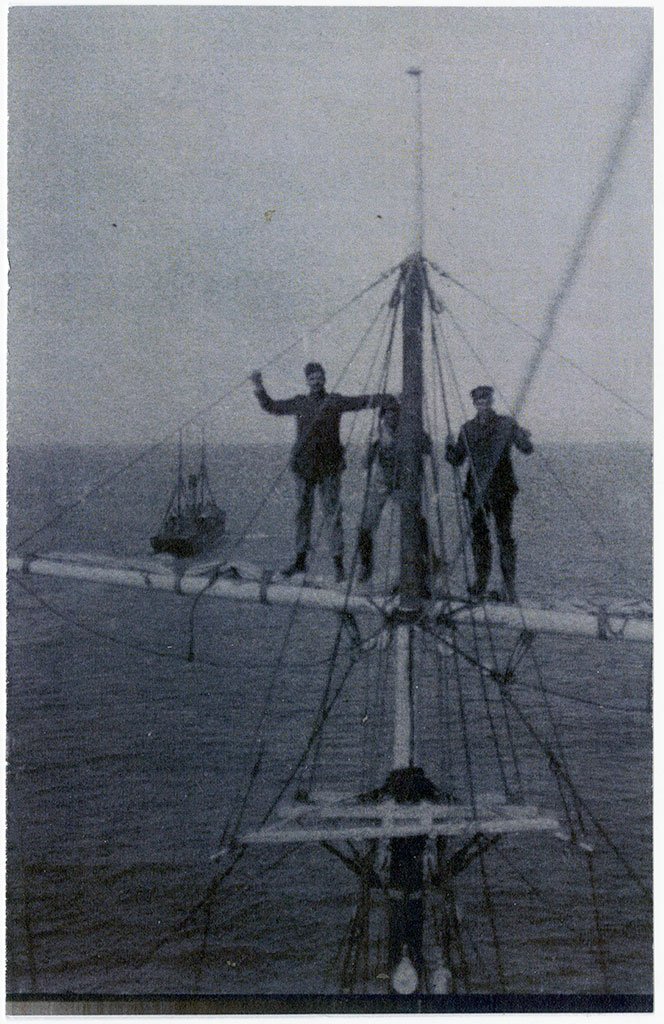

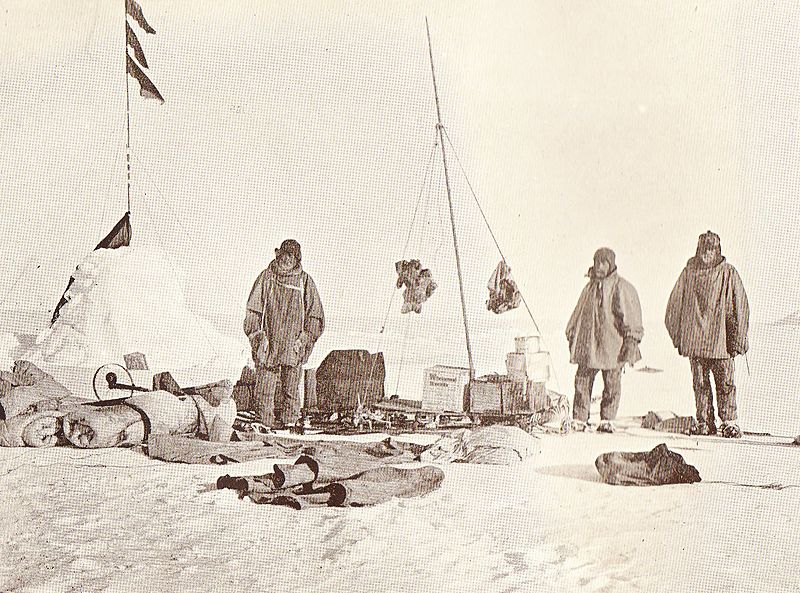

Photo: Crew of the Nimrod waving goodbye to the Koonya.

On 25 January Shackleton ordered the ship to head for McMurdo Sound.

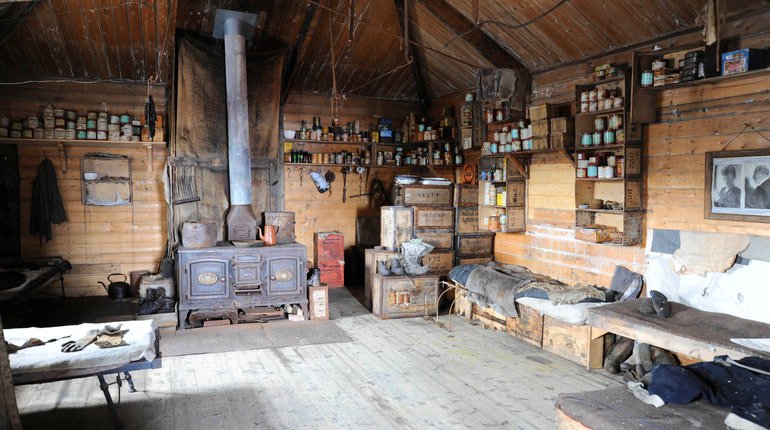

On 3 February Shackleton decided not to wait for the ice to shift but to make his headquarters at the nearest practicable landing place, Cape Royds.

The party reached the Cape Royds hut "nearly dead", according to Eric Marshall, on 11 March.

Shackleton's choice of a four-man team for the southern journey to the South Pole was largely determined by the number of surviving ponies.

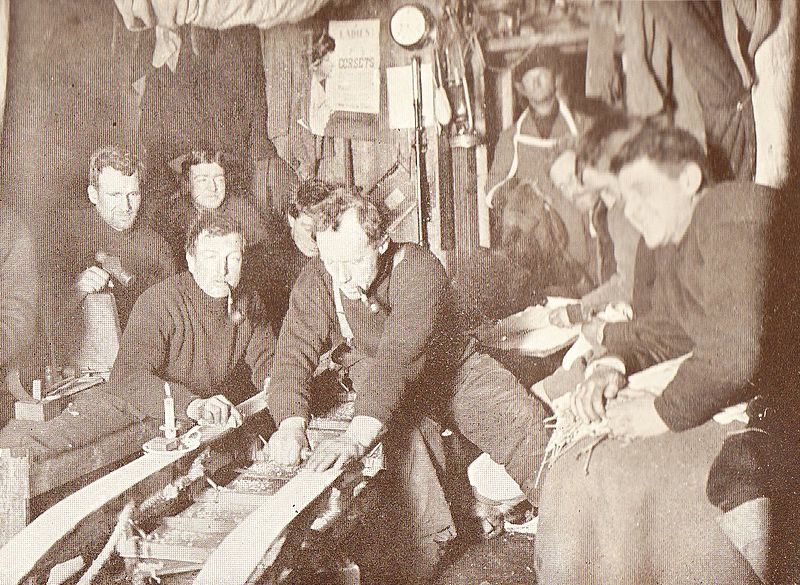

However, Christmas Day was celebrated with crème de menthe and cigars.

That day, referring to Marshall and Adams, Wild wrote: "if we only had Joyce and Marston here instead of those two grubscoffing useless beggars we would have done it easily."

The depot was reached on 28 January.

From 18 February onward they began to pick up familiar landmarks, and on the 23rd they reached Bluff Depot, which to their great relief had been copiously resupplied by Ernest Joyce.

After that, On 23 March 1909, he landed in New Zealand and cabled a 2,500-word report to the London Daily Mail.

Although in the eyes of the public he was a hero, the riches that Shackleton had anticipated failed to materialize.

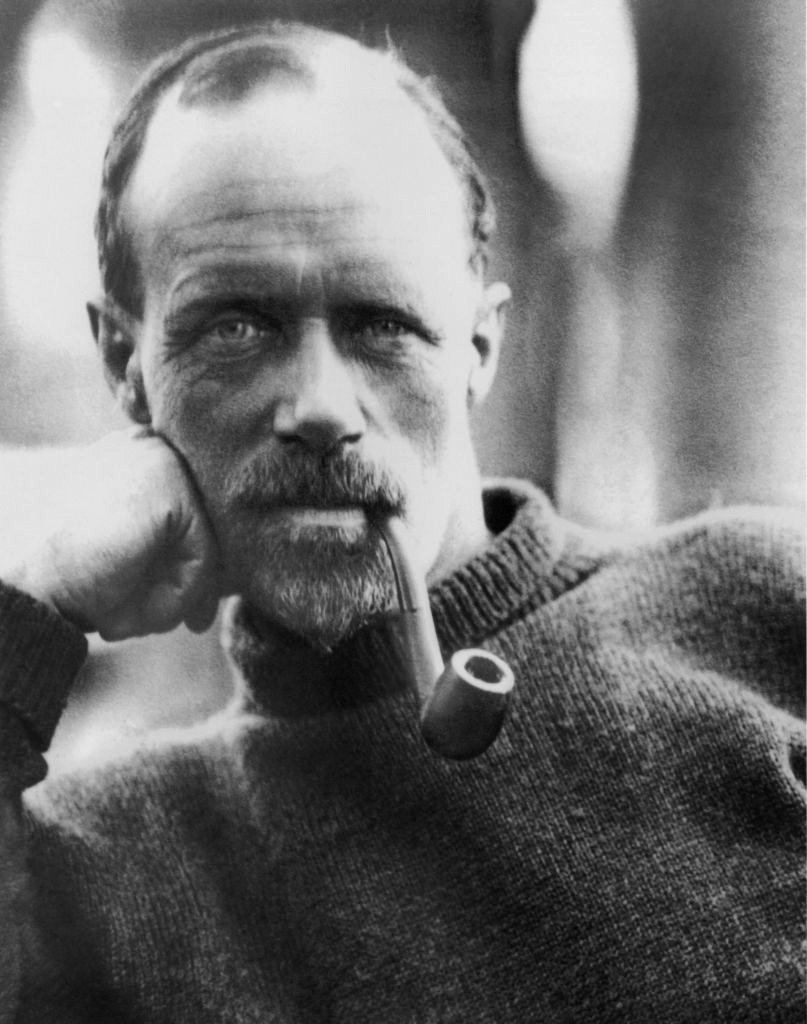

He had spent the previous years drinking heavily.

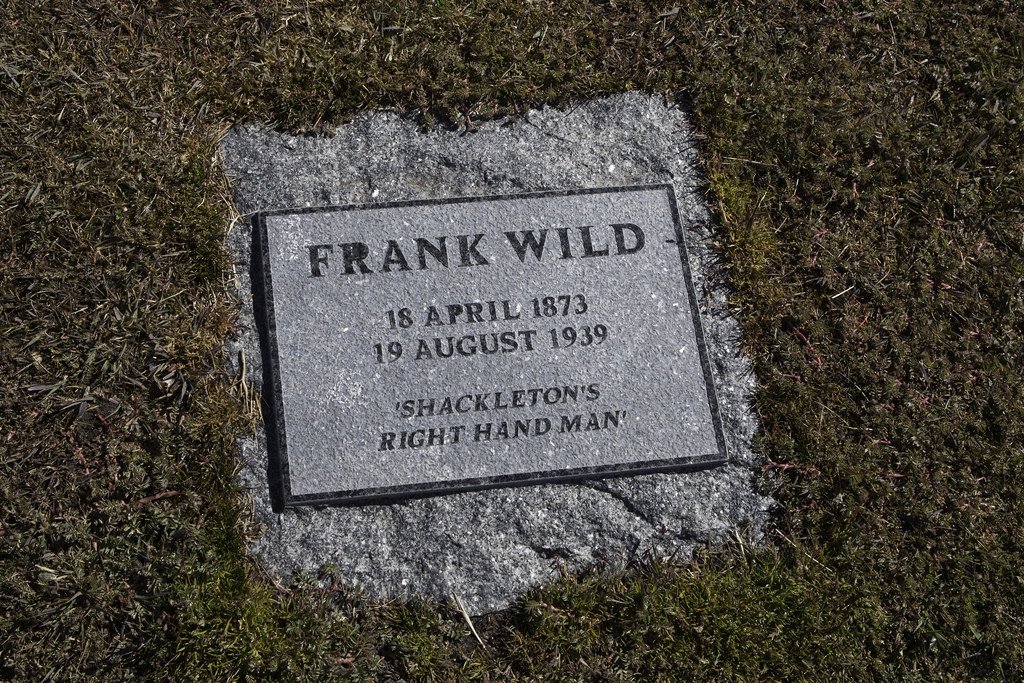

The inscription on the rough-hewn granite block set to mark the spot reads "Frank Wild 1873–1939, Shackleton's right-hand man."

Let me know if you are enjoying these more detailed and extensive threads. :)