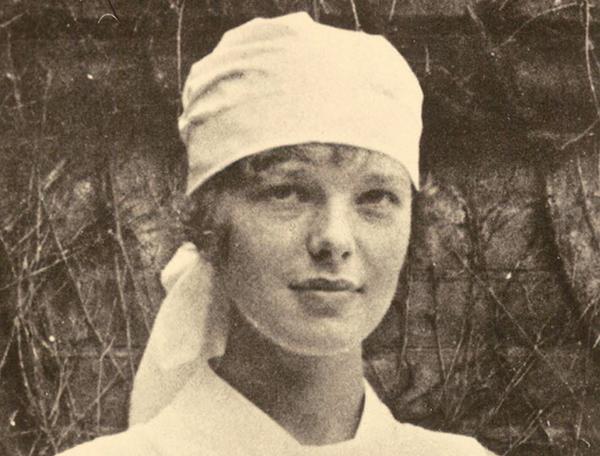

She was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

(The photo is from The Colour of Time tinyurl.com/y9ddsvzj)

"By the time I had got two or three hundred feet [60–90 m] off the ground," she said, "I knew I had to fly."

Working at a variety of jobs including photographer, truck driver, and stenographer at the local telephone company, she managed to save $1,000 for flying lessons.

In order to reach the airfield, Earhart had to take a bus to the end of the line, then walk four miles (6 km).

She chose a leather jacket, but aware that other aviators would be judging her, she slept in it for three nights to give the jacket a "worn" look.

Following her parents' divorce in 1924, she drove her mother on a transcontinental trip from California to Boston, Massachusetts.

Amelia did not pilot the aircraft.

Although she had gained fame for her transatlantic flight, she endeavored to set an "untarnished" record of her own.

With the aircraft severely damaged, the flight was called off and the aircraft was shipped by sea to the Lockheed Burbank facility for repairs.

Around 3 pm Lae time, Earhart reported her altitude as 10000 feet but that they would reduce altitude due to thick clouds. Around 5 pm, Earhart reported her altitude as 7000 feet and speed as 150 knots.