zinnedproject.org/if-we-knew-our…

screenrant.com/watchmen-show-…

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

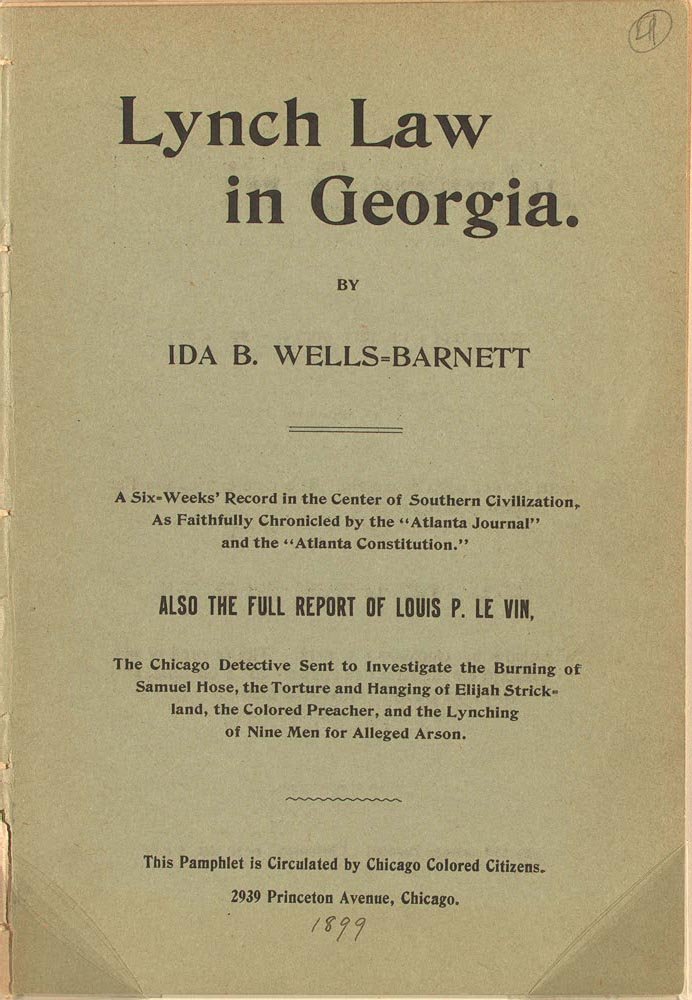

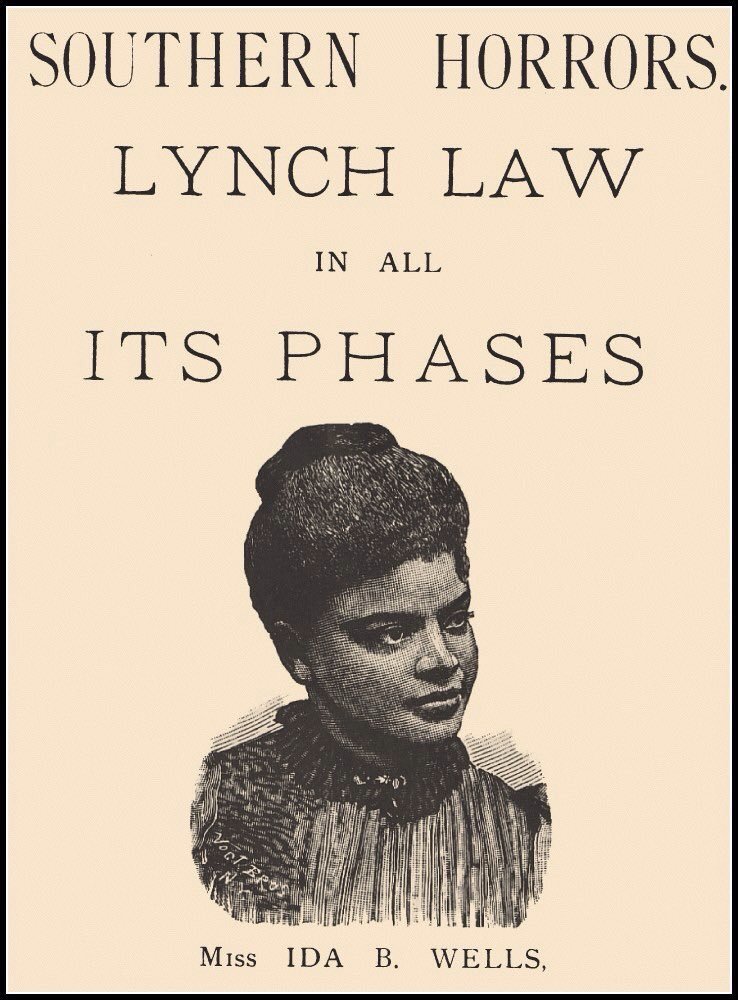

dailykos.com/stories/2019/2…

lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/

lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/#lynchi…

slate.com/human-interest…

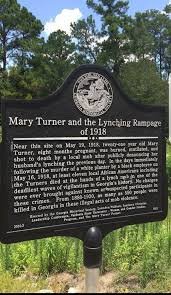

nytimes.com/2018/04/25/us/…

'

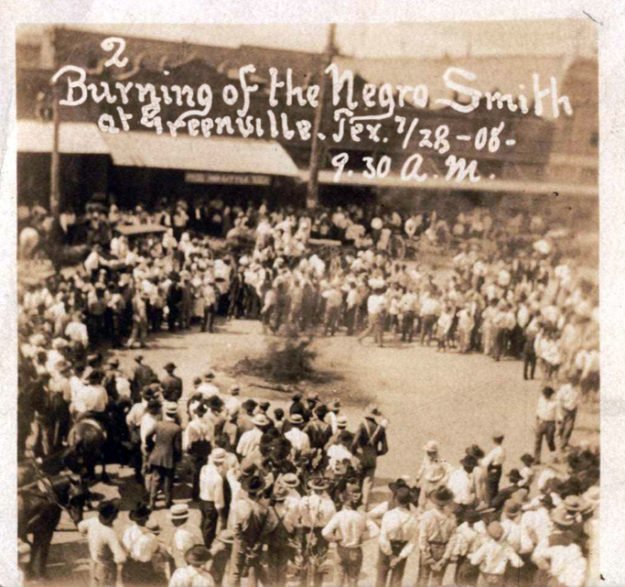

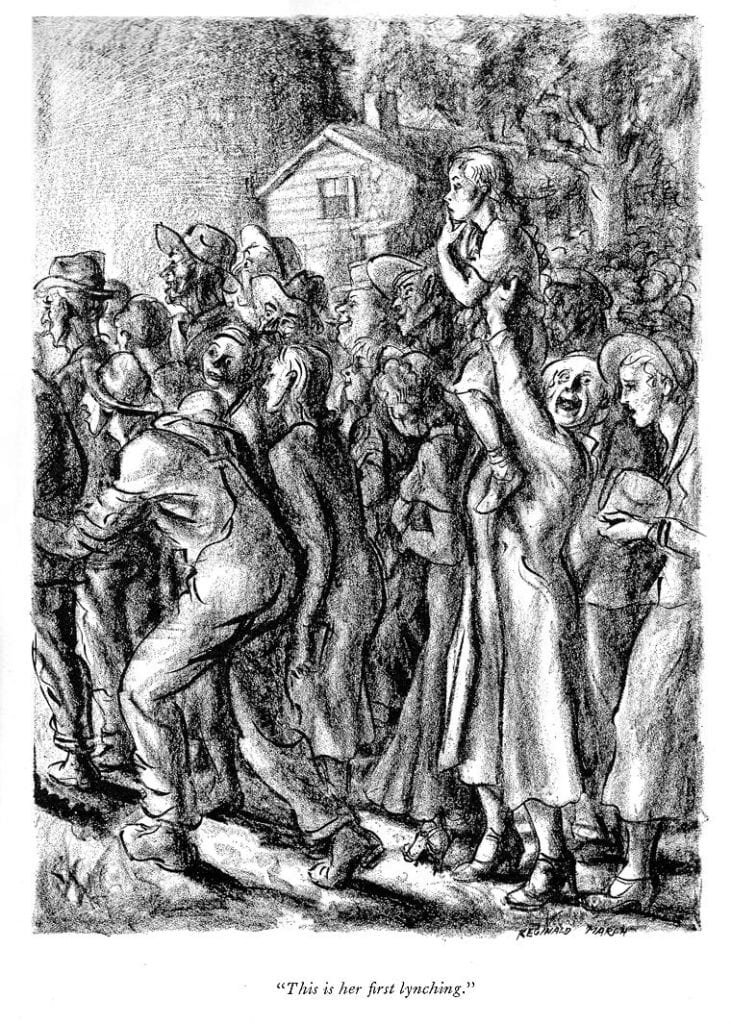

amazon.com/Without-Sanctu…

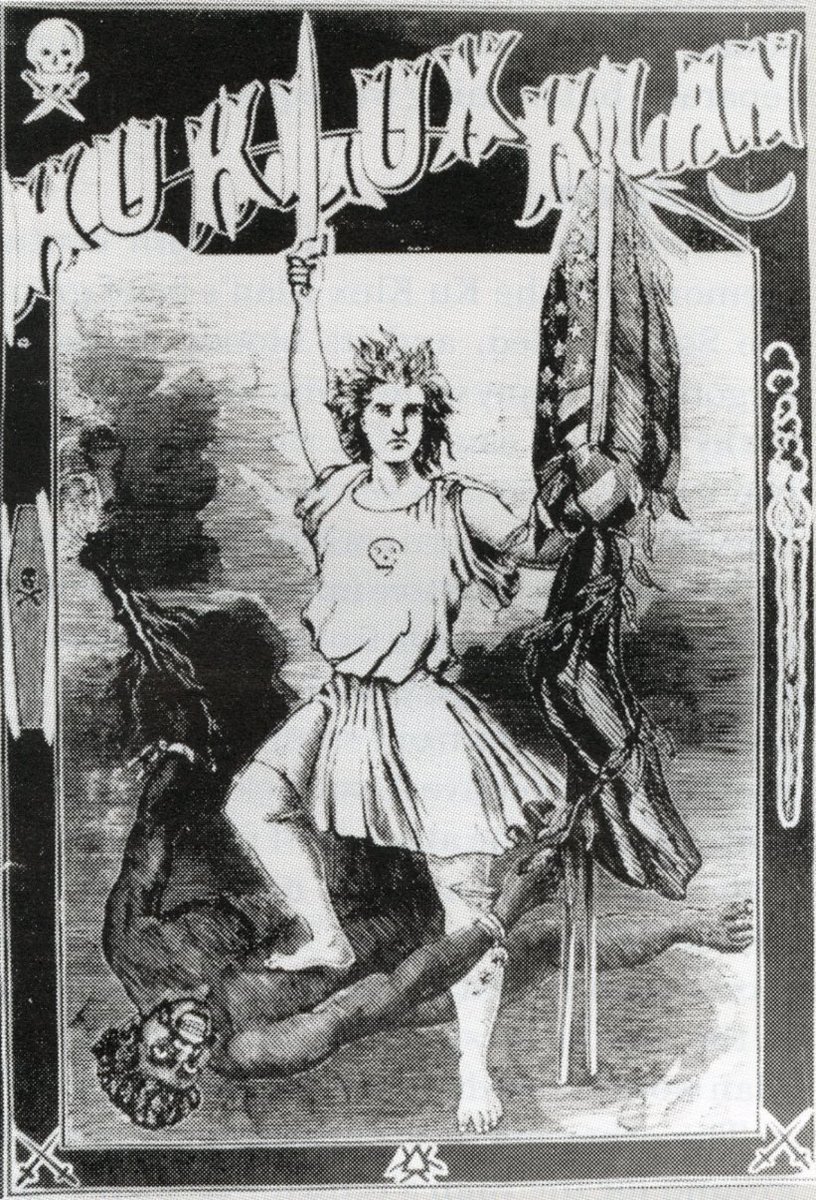

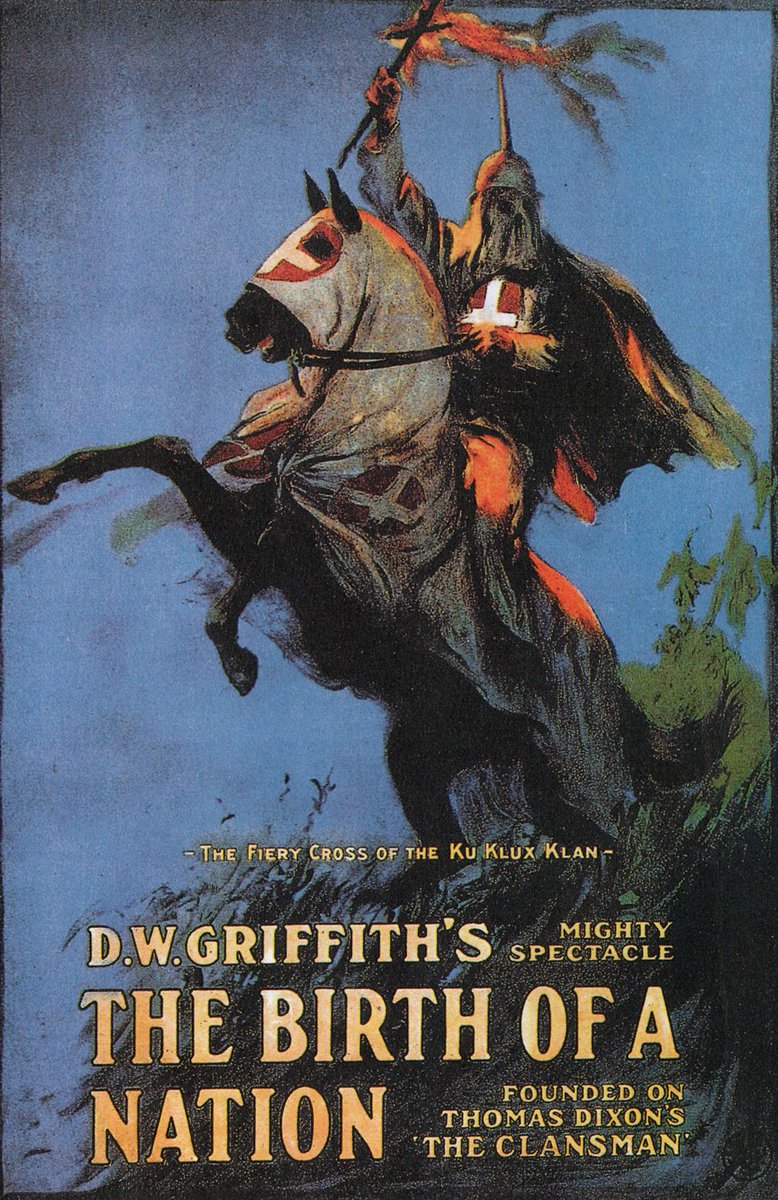

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Clans…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Birth…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nadir_of_…

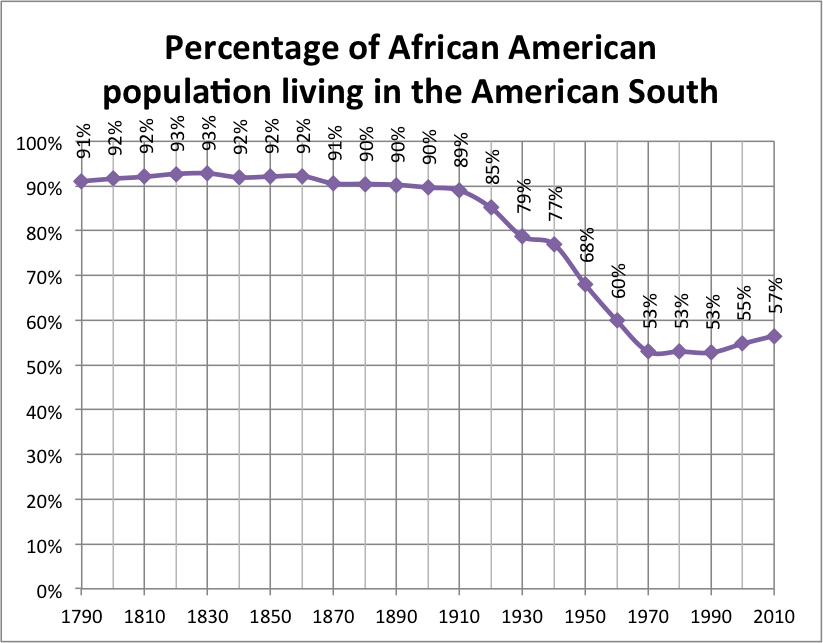

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Mig…

smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-in…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_A…

eji.org/reports/online…

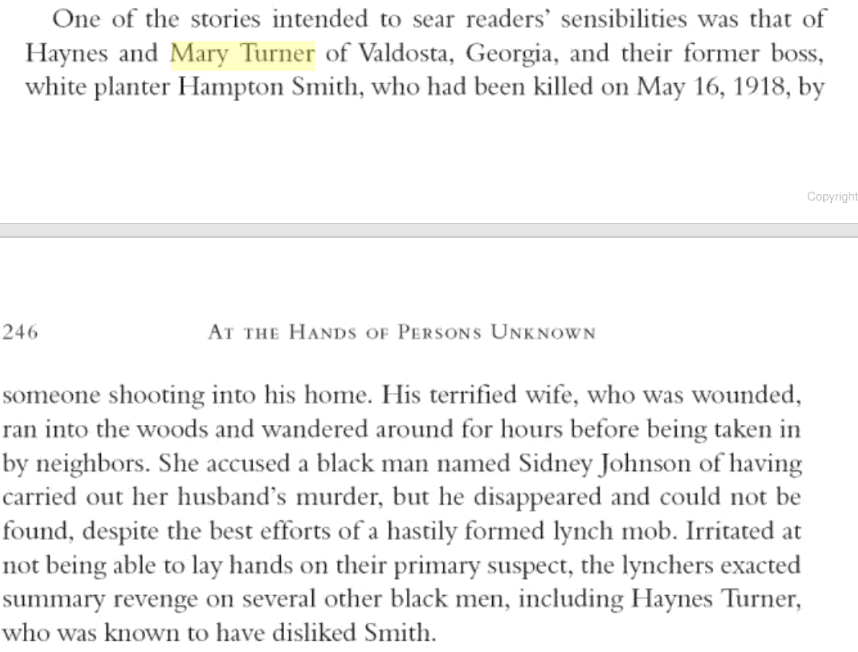

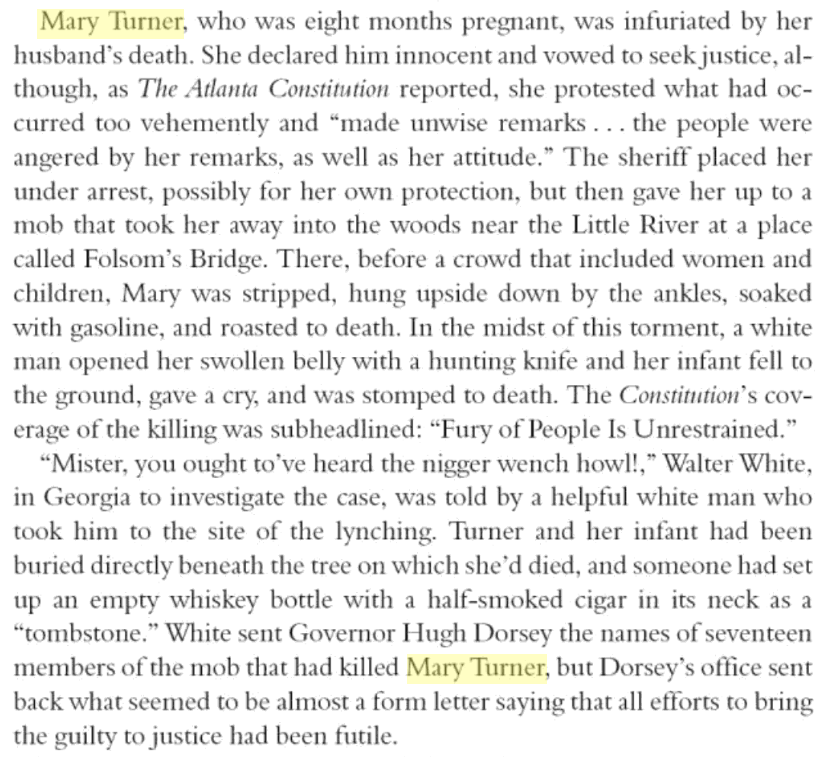

penguinrandomhouse.com/books/42828/at…

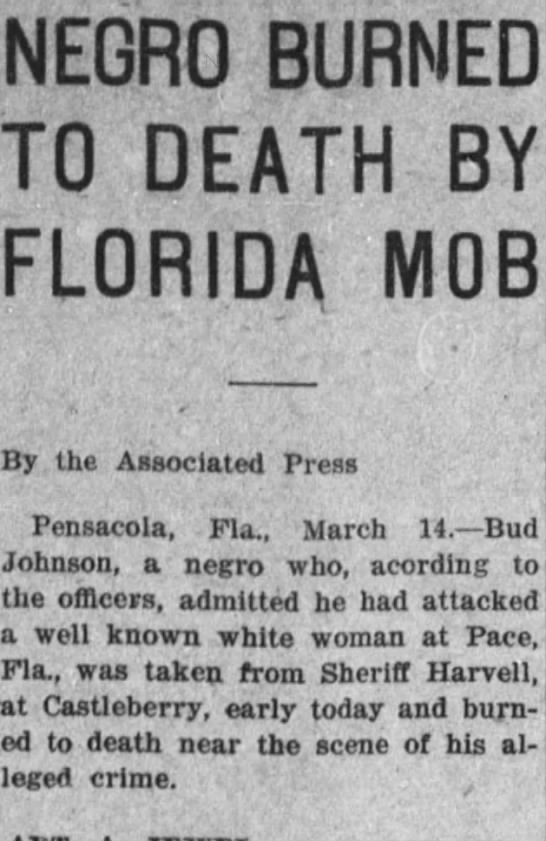

pensacolian.com/2019/03/13/the…

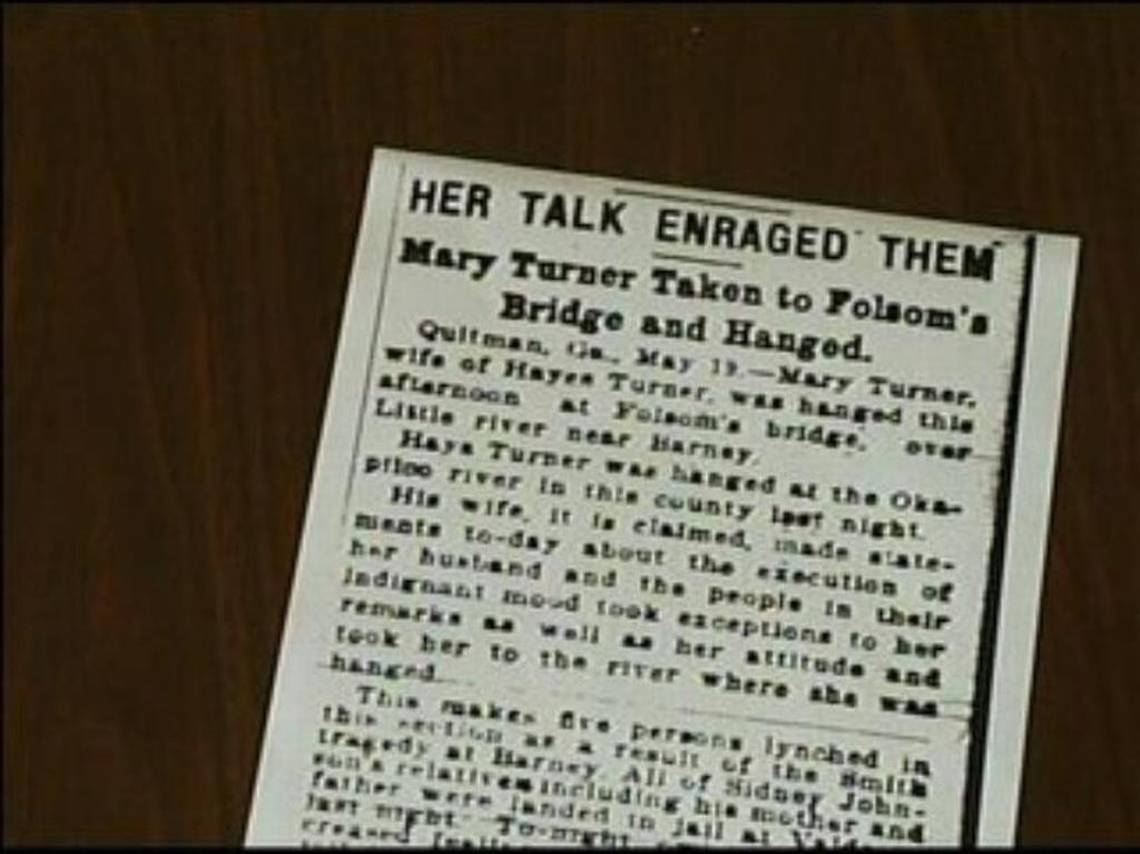

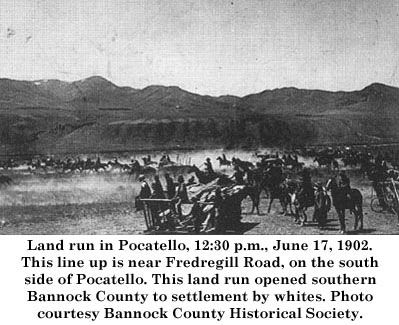

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/jenk…

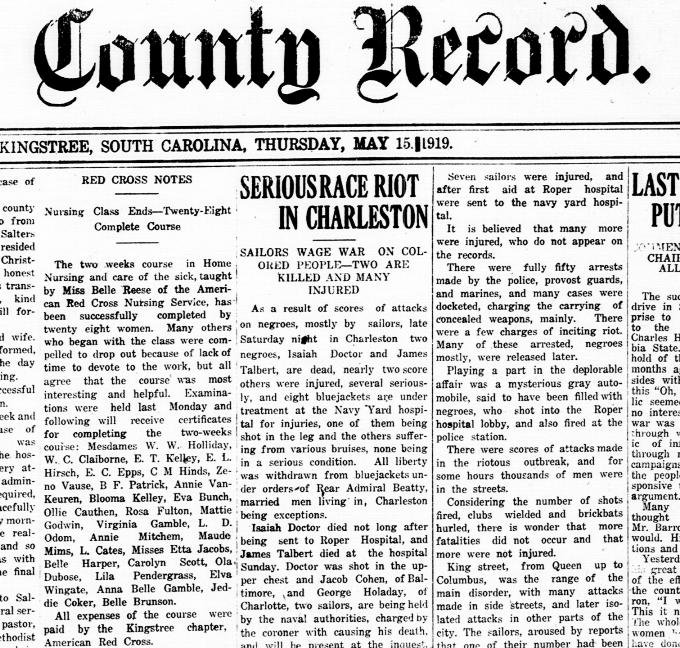

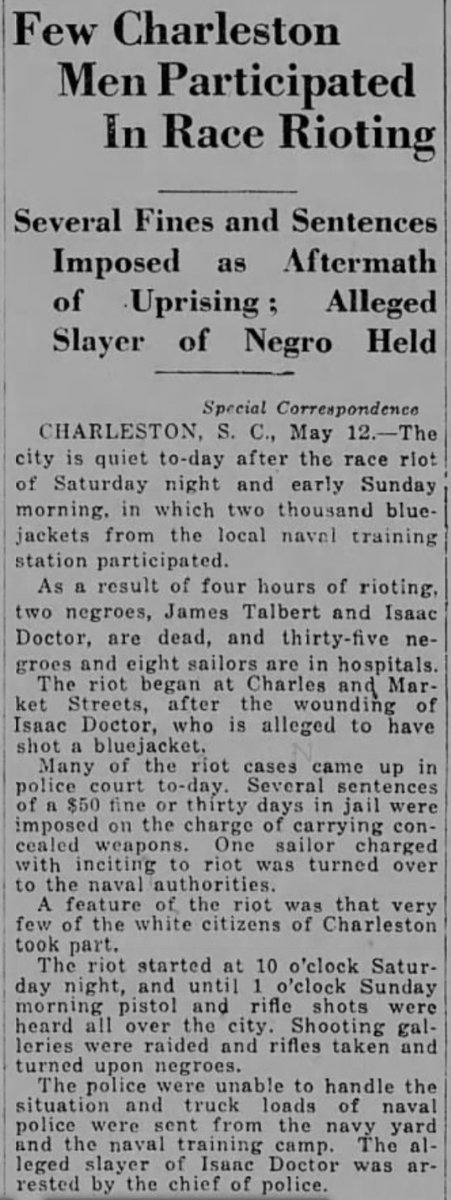

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/char…

encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/frank-…

janvoogd.wordpress.com/2009/05/25/90t…

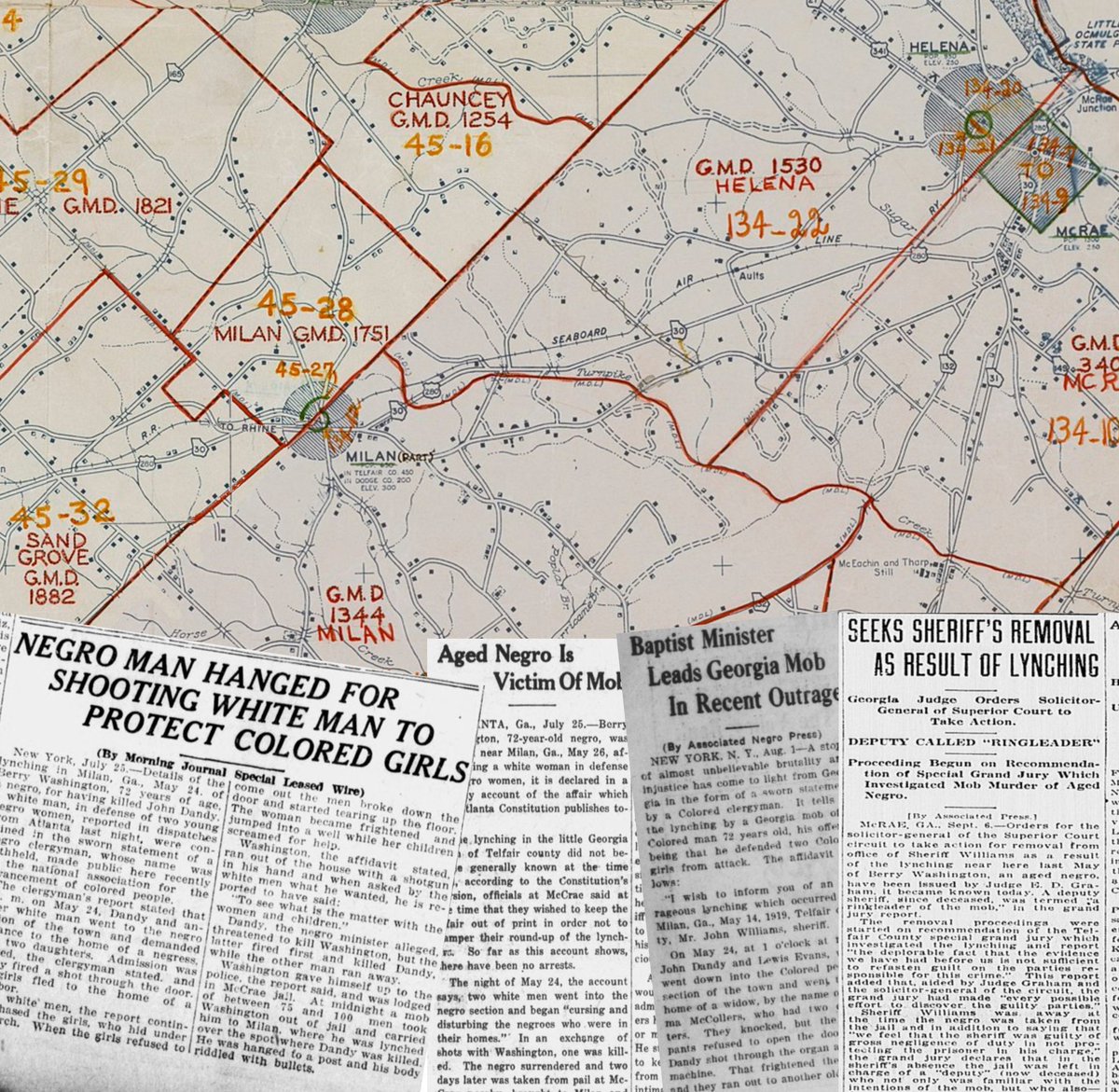

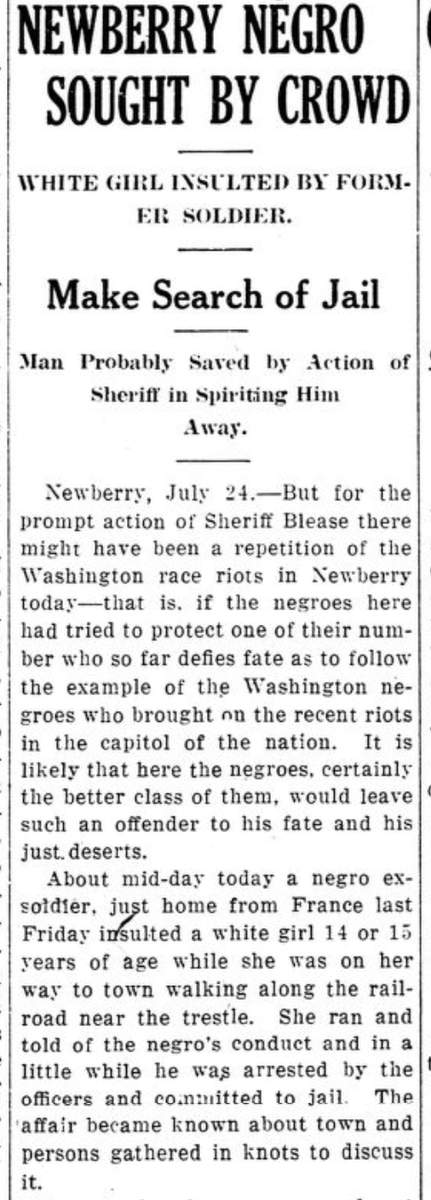

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Putnam_Co…

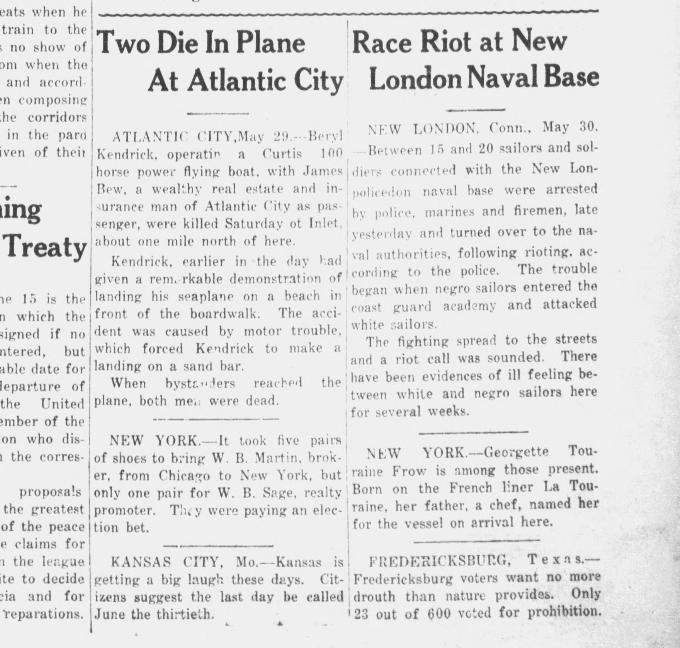

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Londo…

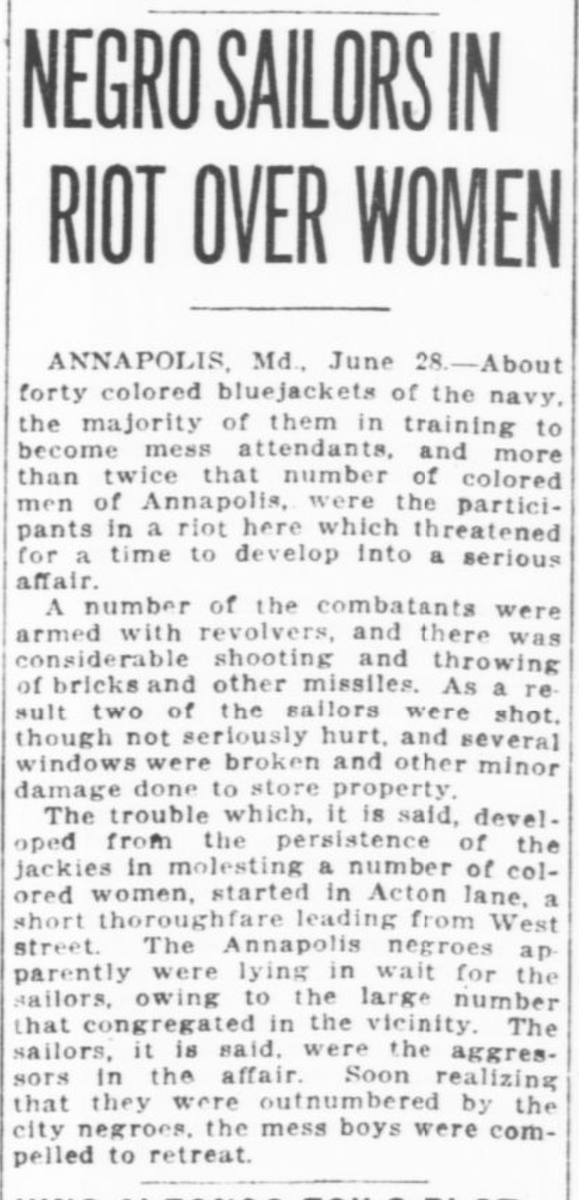

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annapolis…

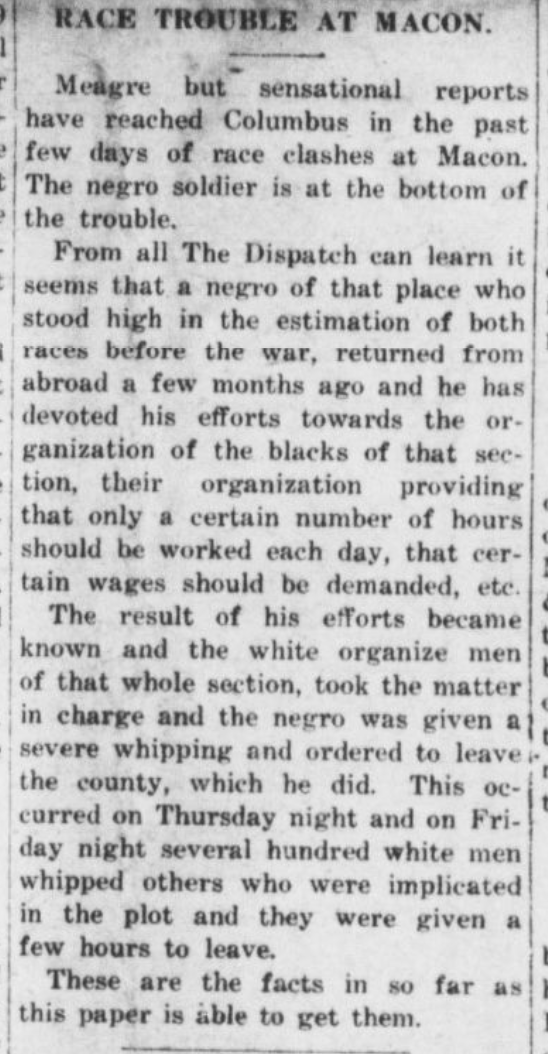

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macon,_Mi…

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/brew…

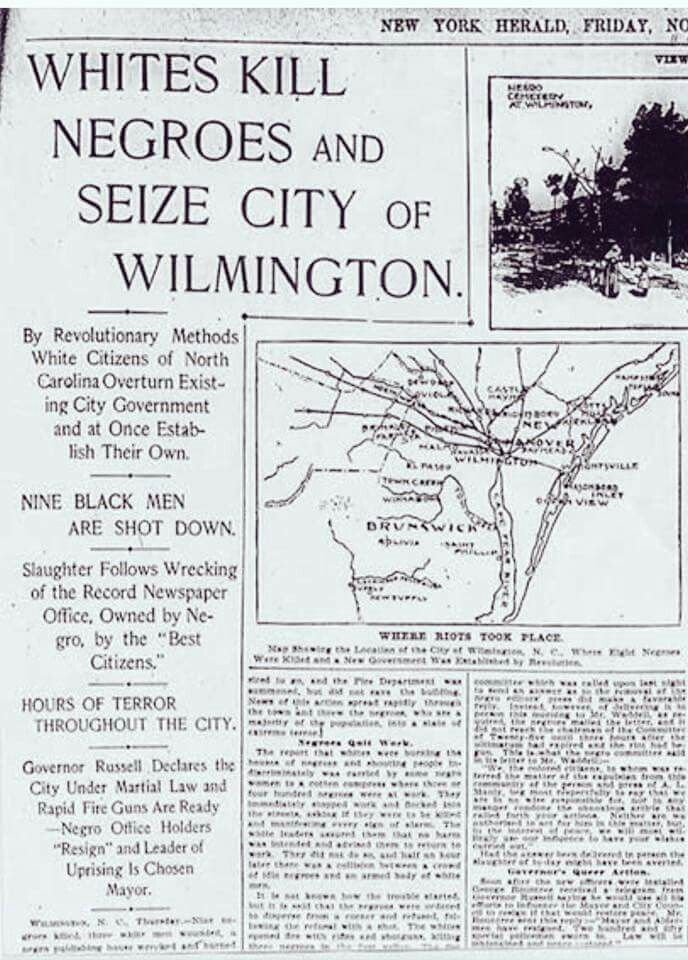

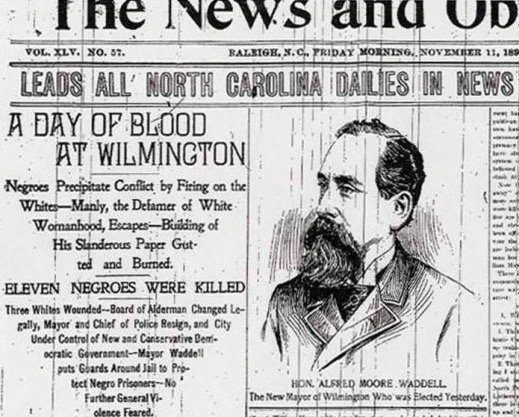

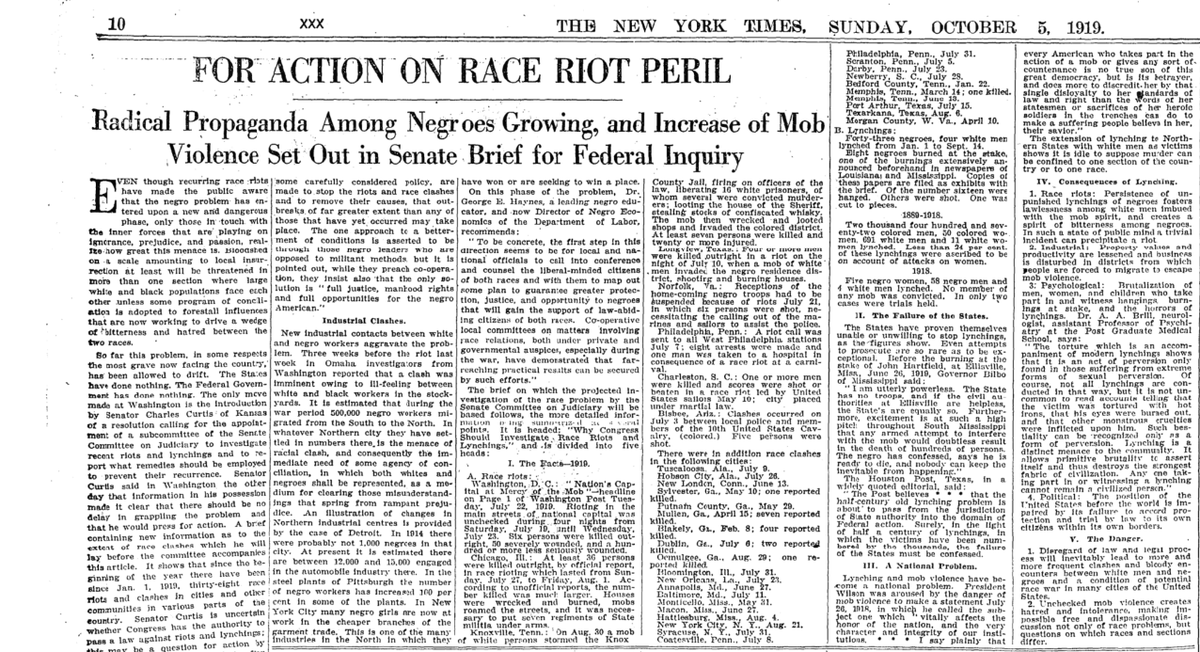

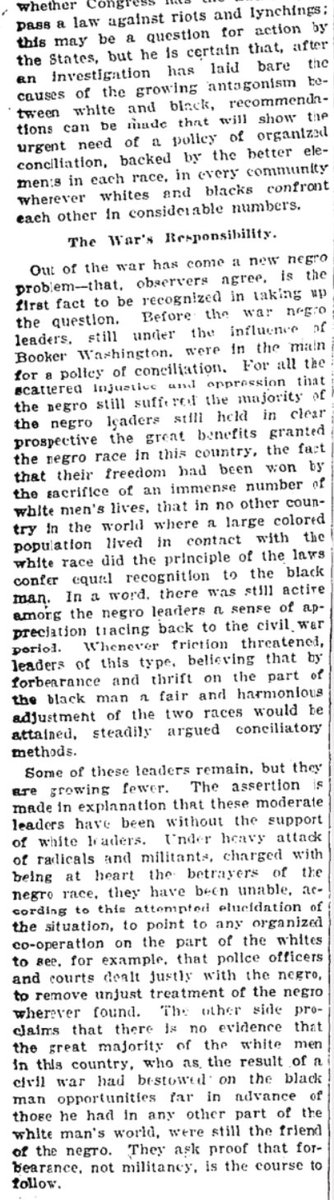

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Race_riot…

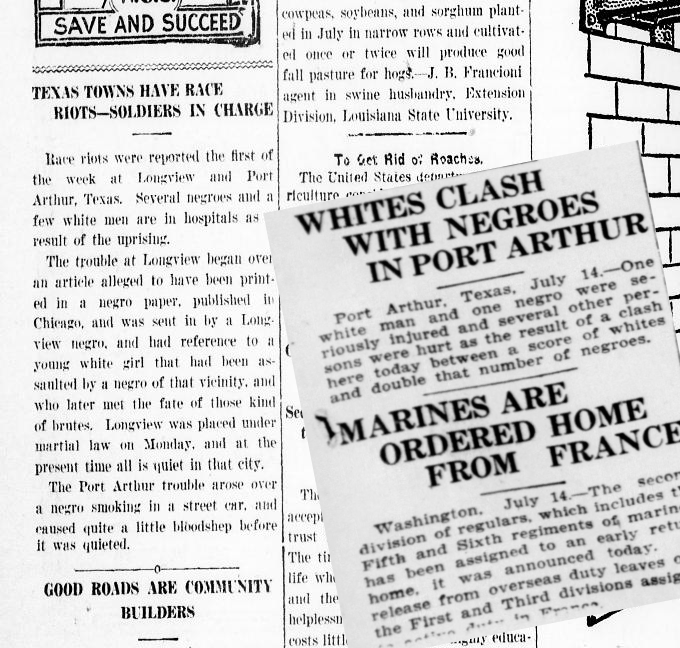

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/long…

taskandpurpose.com/tragic-ignored…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Arth…

blackpast.org/african-americ…

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/red-…

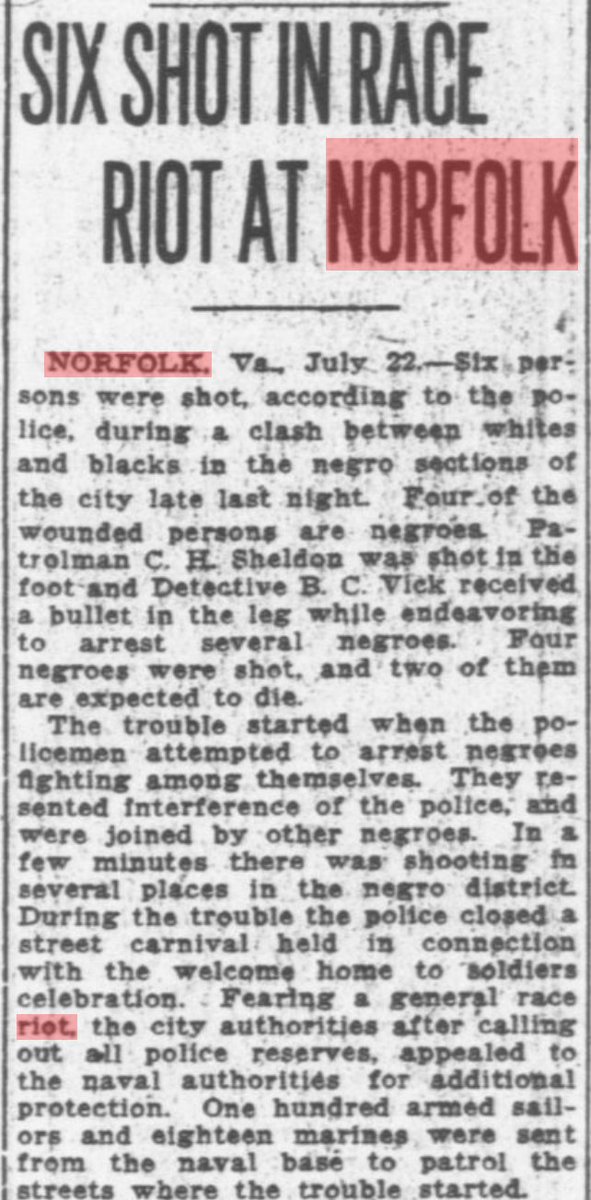

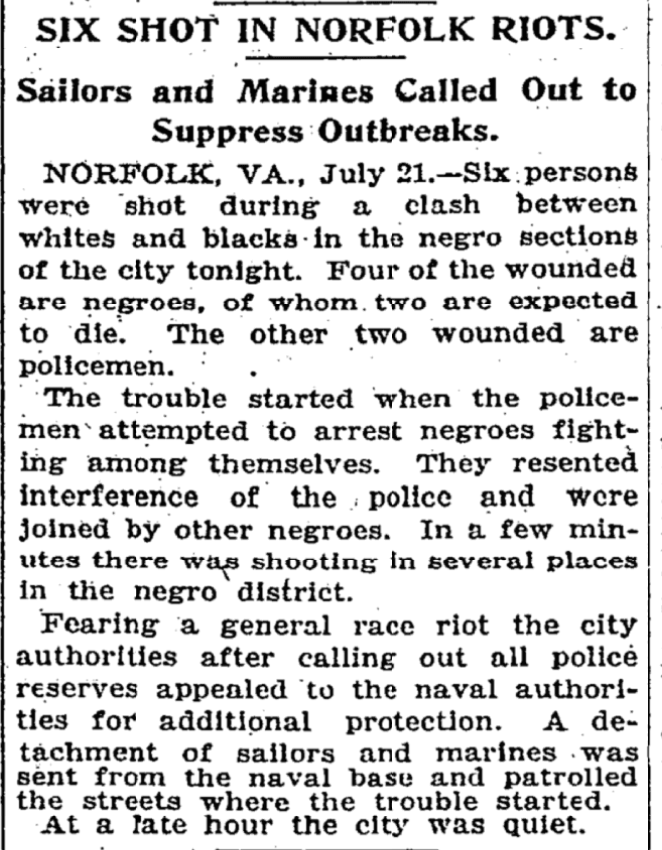

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1919_Norf…

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/riot…

britannica.com/event/Chicago-…

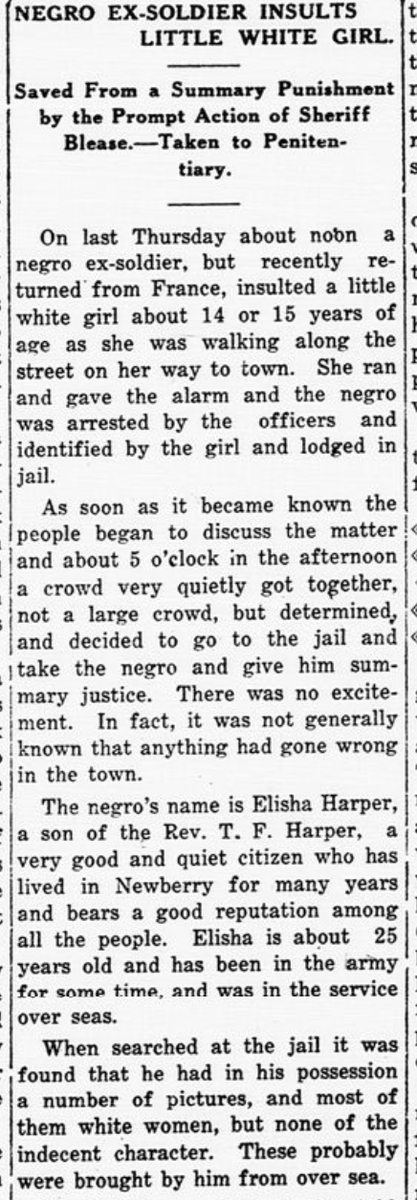

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newberry_…

encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/clinto…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurens_C…

tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=…

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/omah…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Pa…

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/elai…

encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/elaine…

patrickmurfin.blogspot.com/2019/10/the-el…

cnn.com/2019/09/28/us/…

npr.org/templates/stor…

books.google.com/books/about/Su…

zinnedproject.org/if-we-knew-our…

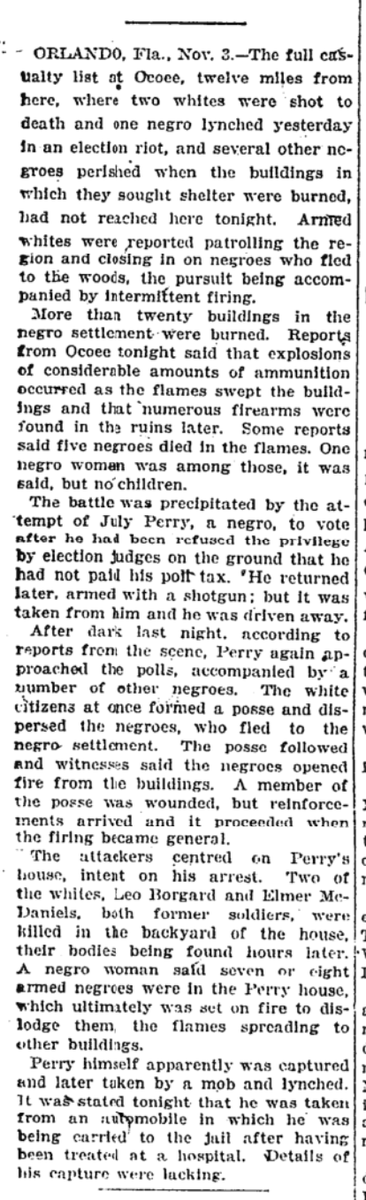

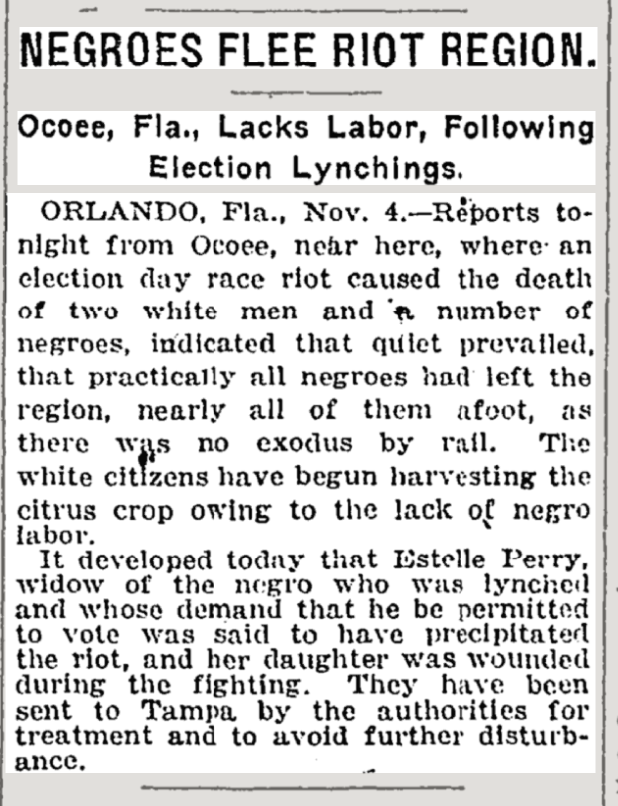

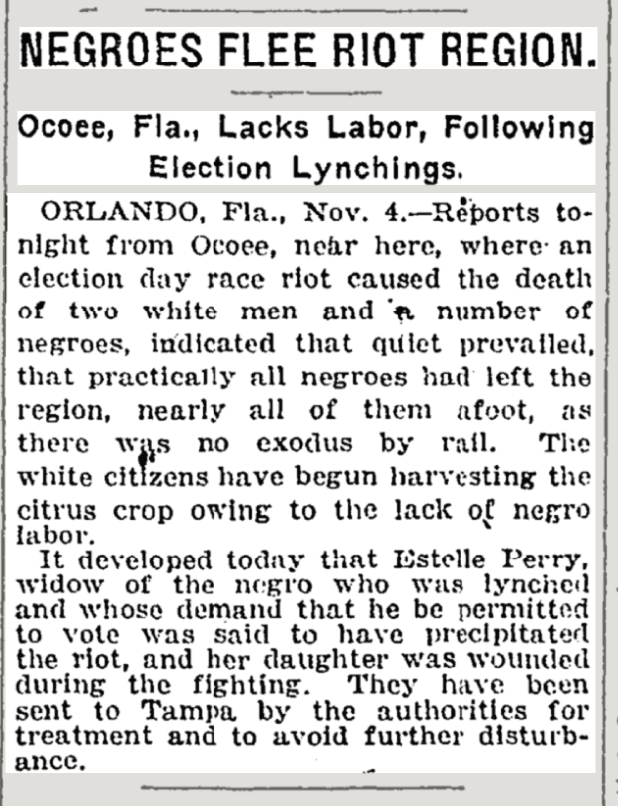

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/ocoe…

eji.org/news/eji-unvei…

facingsouth.org/2010/05/ocoee-…

medium.com/florida-histor…

books.google.com/books/about/Su…

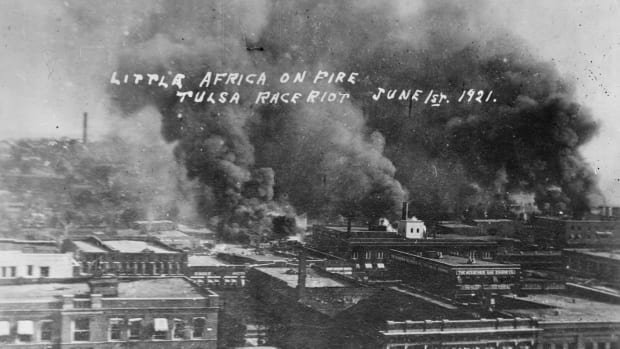

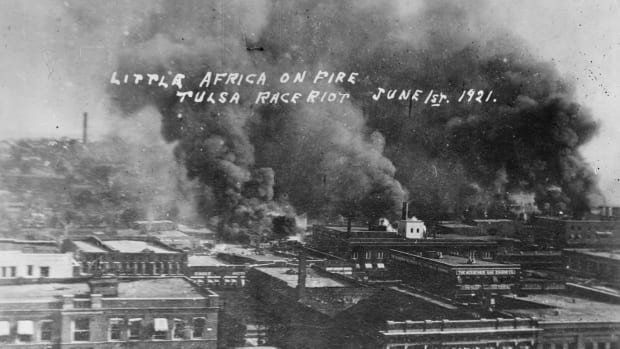

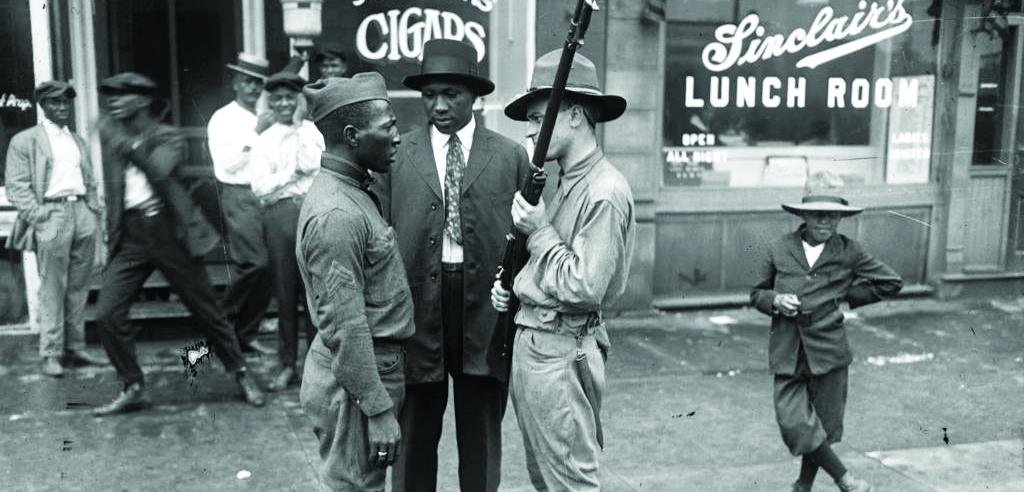

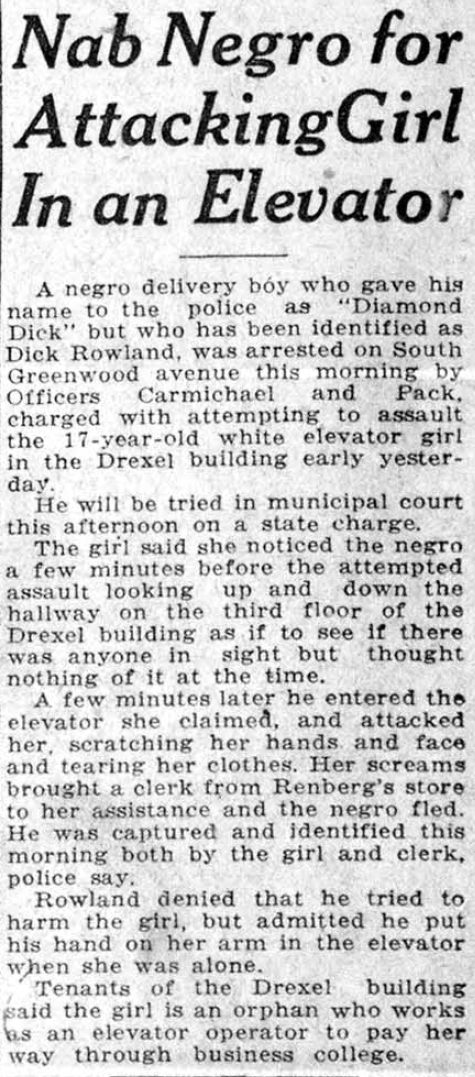

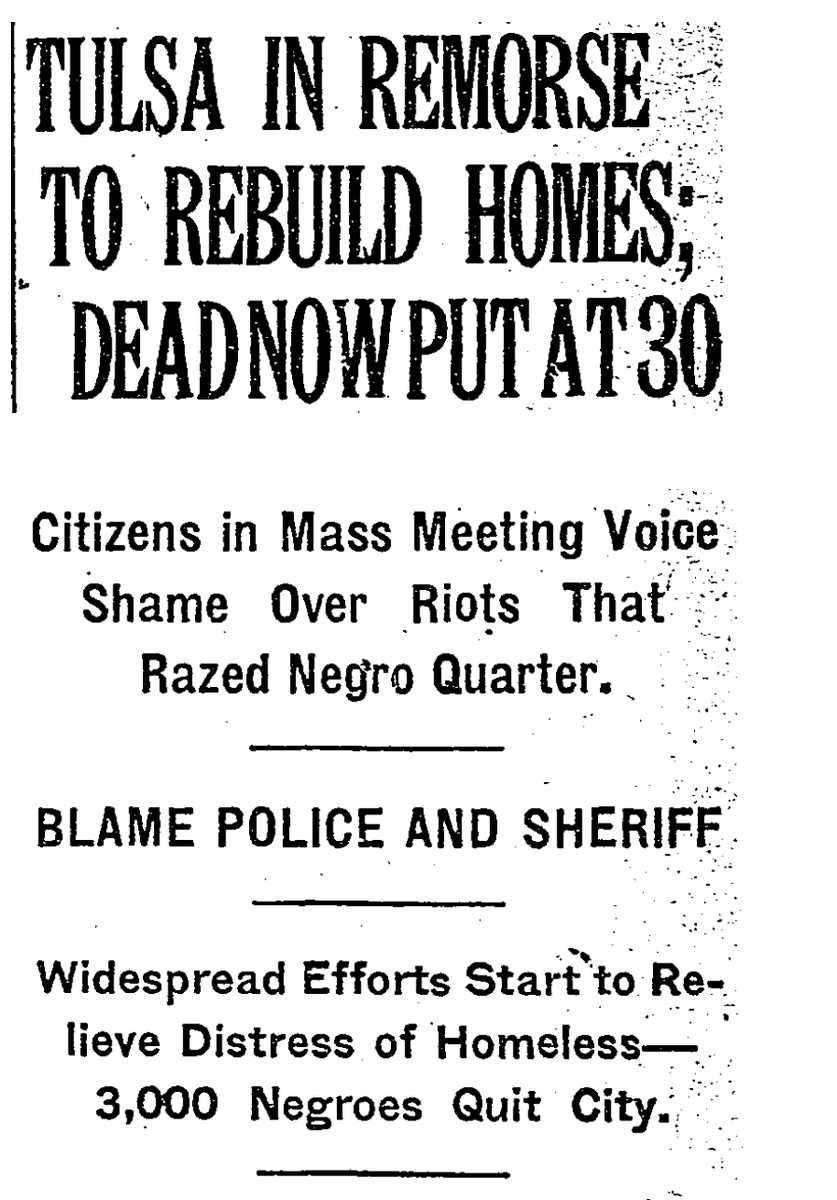

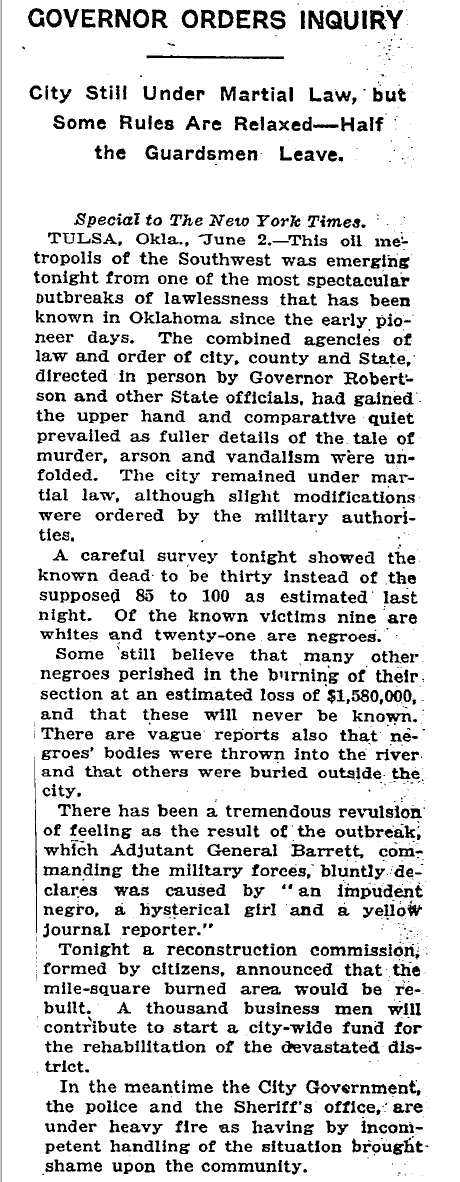

zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/tuls…

timeline.com/history-tulsa-…

history.com/topics/roaring…

smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-in…

vox.com/2016/6/1/11827…

history.com/topics/early-2…

ajc.com/news/national/…

washingtonpost.com/archive/lifest…

timeline.com/all-black-town…

proquest.com/blog/eosblog/2…

huffpost.com/entry/1917-sil…

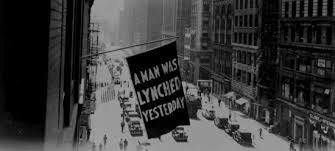

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_man_was…

washingtonpost.com/outlook/2018/1…

gilderlehrman.org/history-now/es…

prospect.org/justice/civil-…

theguardian.com/us-news/2018/a…

zinnedproject.org/if-we-knew-our…

books.google.com/books/about/Su…

abhmuseum.org/sundown-towns-…

csmonitor.com/USA/Society/20…

sundown.tougaloo.edu/sundowntowns.p…

books.google.com/books/about/Re…

zinnedproject.org/if-we-knew-our…

nytimes.com/2019/08/31/us/…

theroot.com/nearly-100-yea…

lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/#legacy…

heraldsun.com/opinion/articl…

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

amazon.com/White-Ally-Too…

monroeworktoday.org/lynching.html

museumandmemorial.eji.org

sundown.tougaloo.edu/sundowntowns.p…

Additional reading:

amazon.com/Red-Summer-Awa…

amazon.com/1919-Year-Raci…

amazon.com/Laps-Gods-Summ…

amazon.com/Without-Sanctu…

amazon.com/At-Hands-Perso…

amazon.com/Lynching-Spect…