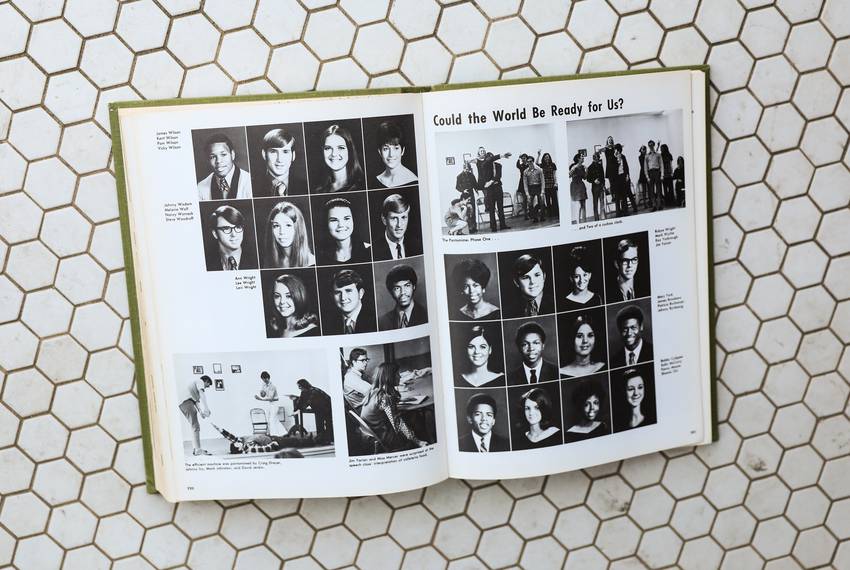

48 years ago, a judge ordered the Longview school district to desegregate its schools.

But an educational gap remains. And some fear the progress that’s been made could be lost. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

And in Longview, students of color still don’t have the same educational opportunities as white students. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

Compare that with a dismal 23 percent of Hispanic students and 16 percent of black students. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

After all, a judge lifted the desegregation court order this June.

But will Longview continue to improve without federal oversight?

bit.ly/2BEzw0U

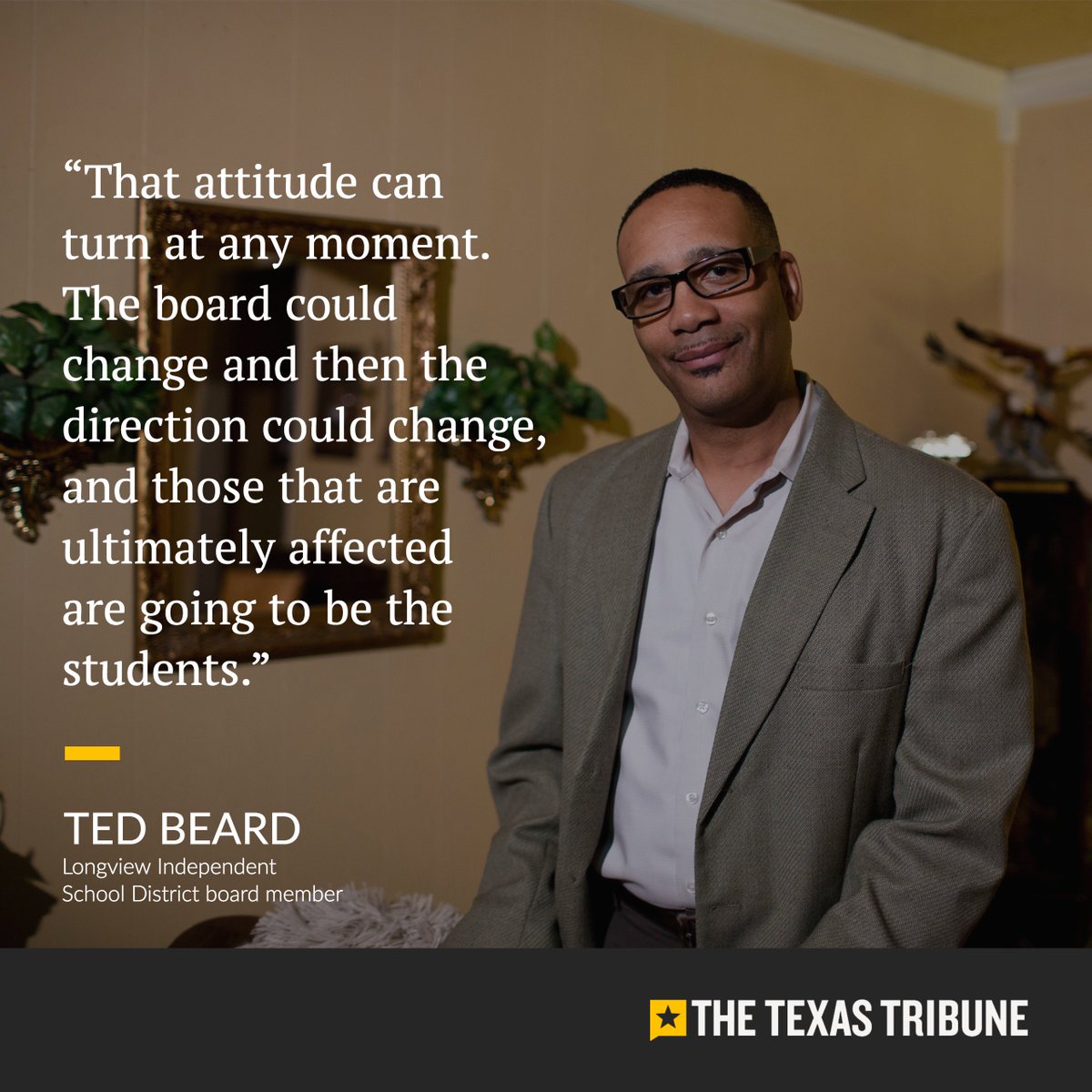

Beard knows the district’s commitment to student equity now depends on the collective will of a school board that could change with a single election cycle.

bit.ly/2BEzw0U

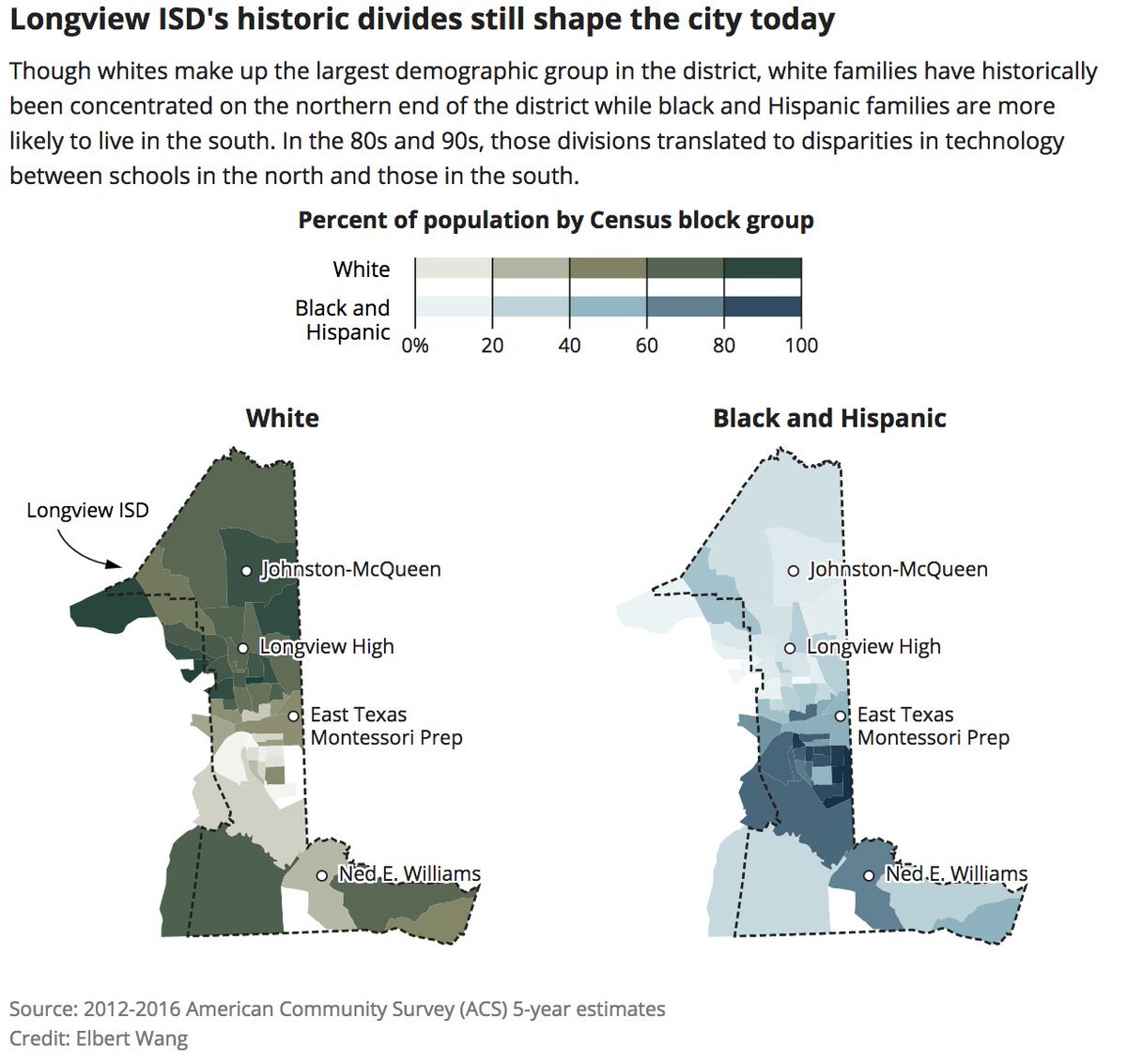

When the court issued its ruling in 1970, folks in Longview saw the federal push for integration as a threat to their autonomy.

Some reacted with violence. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

They collected lethal weapons like hand grenades, dynamite and Molotov cocktails. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

They were later convicted.

They each drew 11 years in prison.

bit.ly/2BEzw0U

It passed by fewer than 20 votes.

That was in 2008 — decades after the court order. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

bit.ly/2BEzw0U

Longview ISD made more progress integrating black students after 2008 than it had in the previous 15 years, an analyst says. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

If the district had spent almost 50 years trying and failing to completely close the educational gap between white, black and Hispanic students with a mandate from a federal court, some wonder if it can succeed without one. bit.ly/2BEzw0U

And people are divided on how they recount the racially fraught history or whether they acknowledge that same racism still exists today.

bit.ly/2BEzw0U

He’s tired. He was thinking about retiring from the board. But he says leaving is not a decision he can make without considering the impact.

bit.ly/2BEzw0U

What if his seat falls to someone who wants to reverse the gains of the past 48 years? bit.ly/2BEzw0U

Read our full story here. bit.ly/2BEzw0U