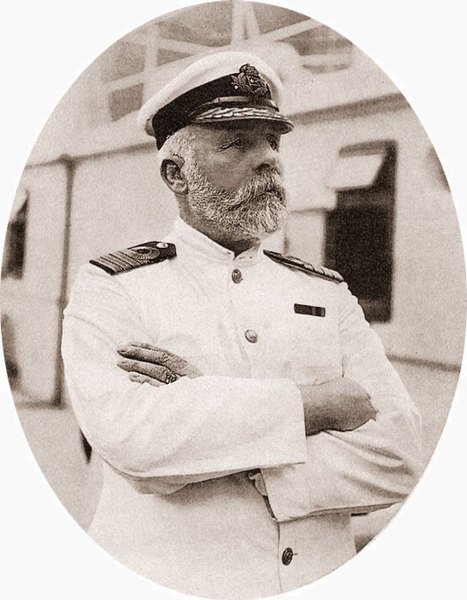

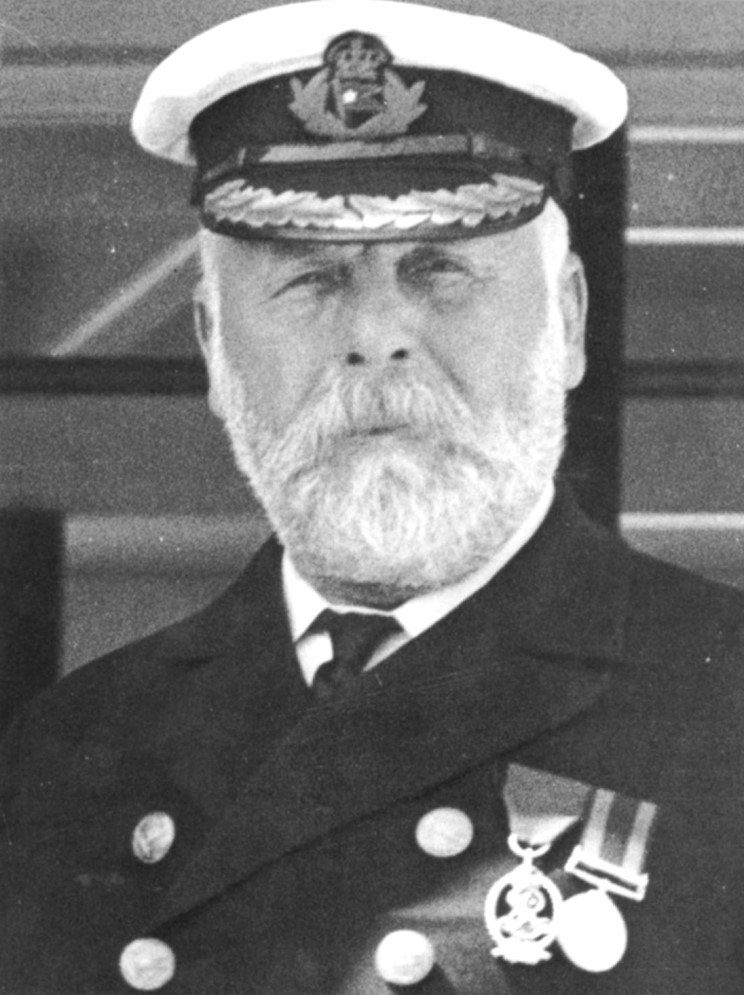

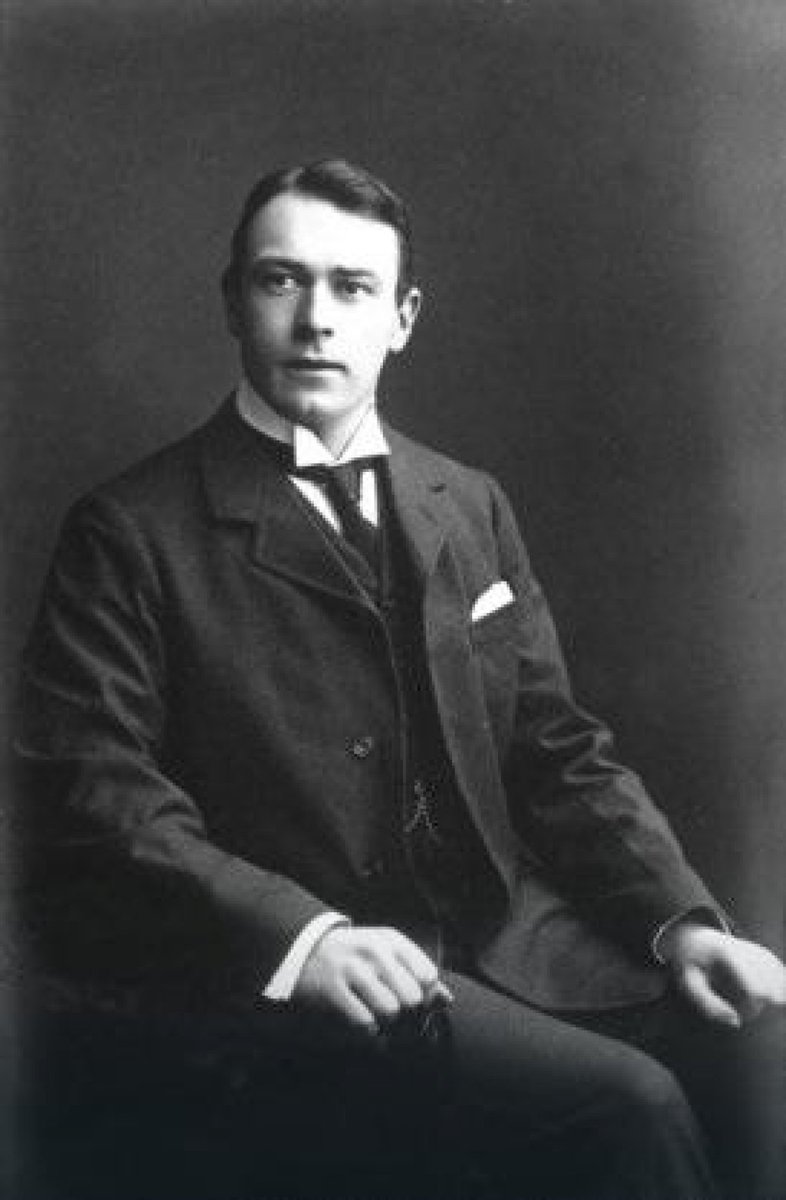

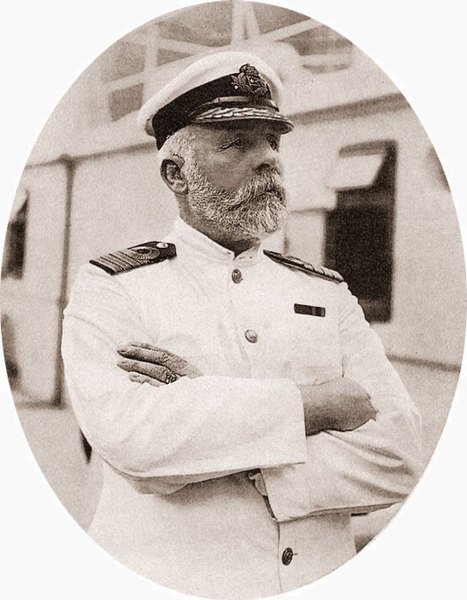

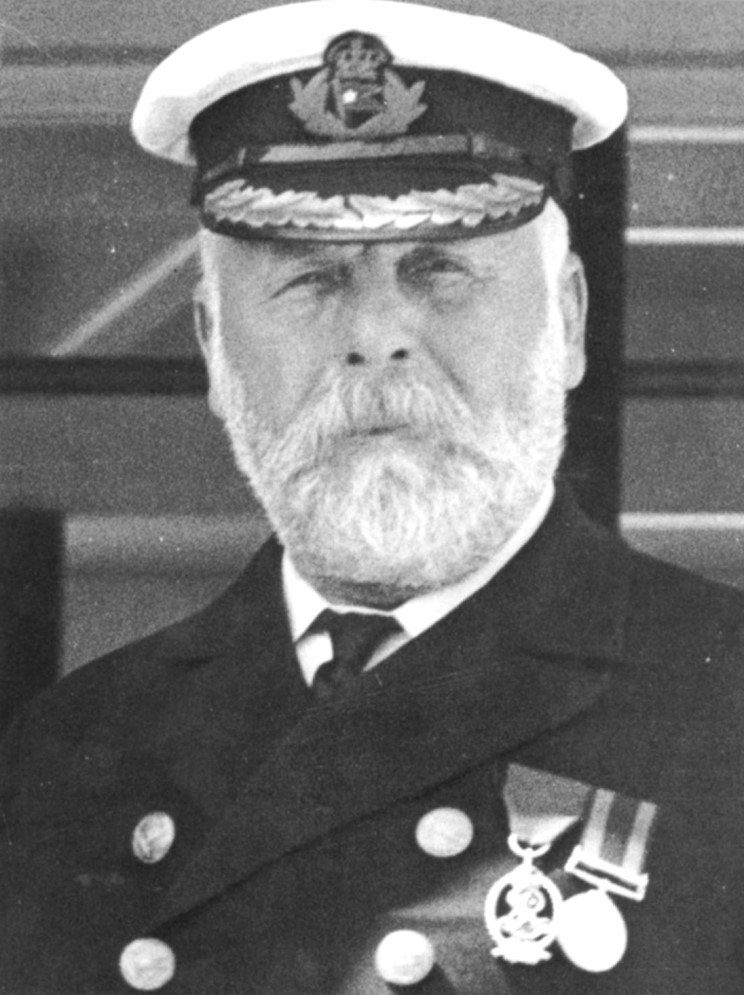

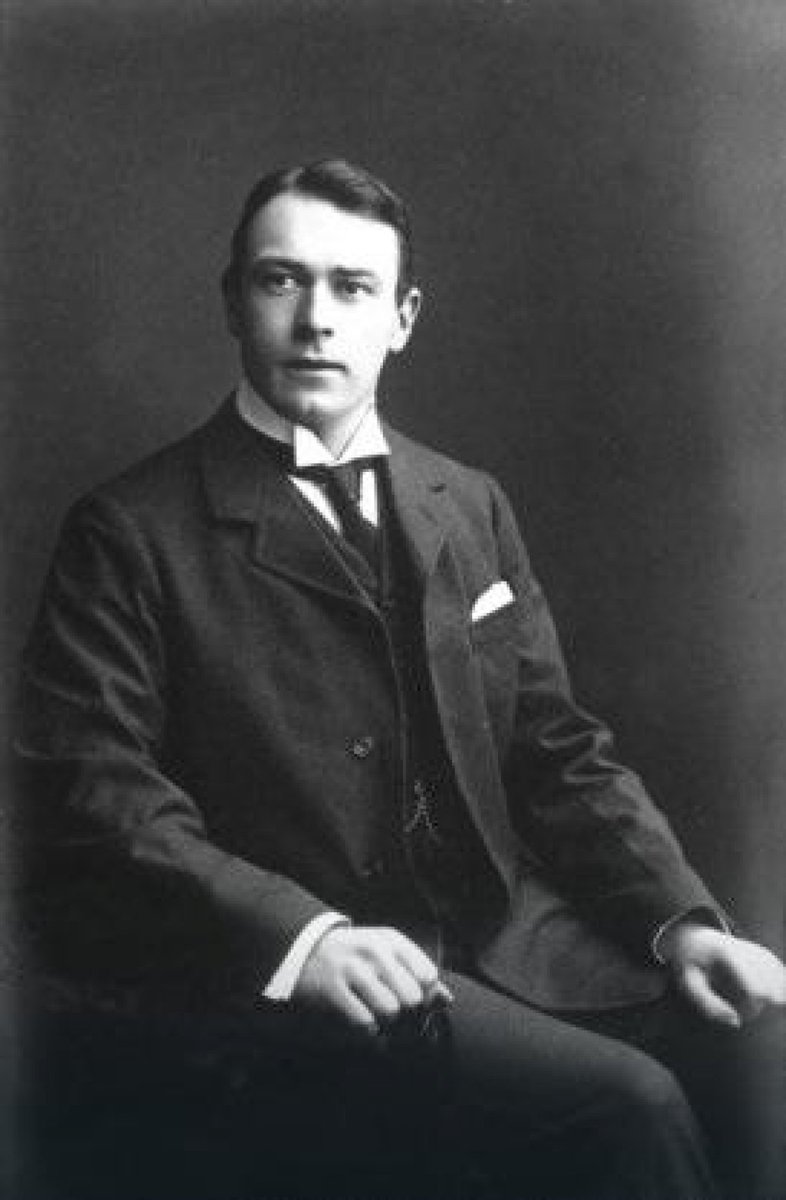

Photo: Chief Engineer William Bell.

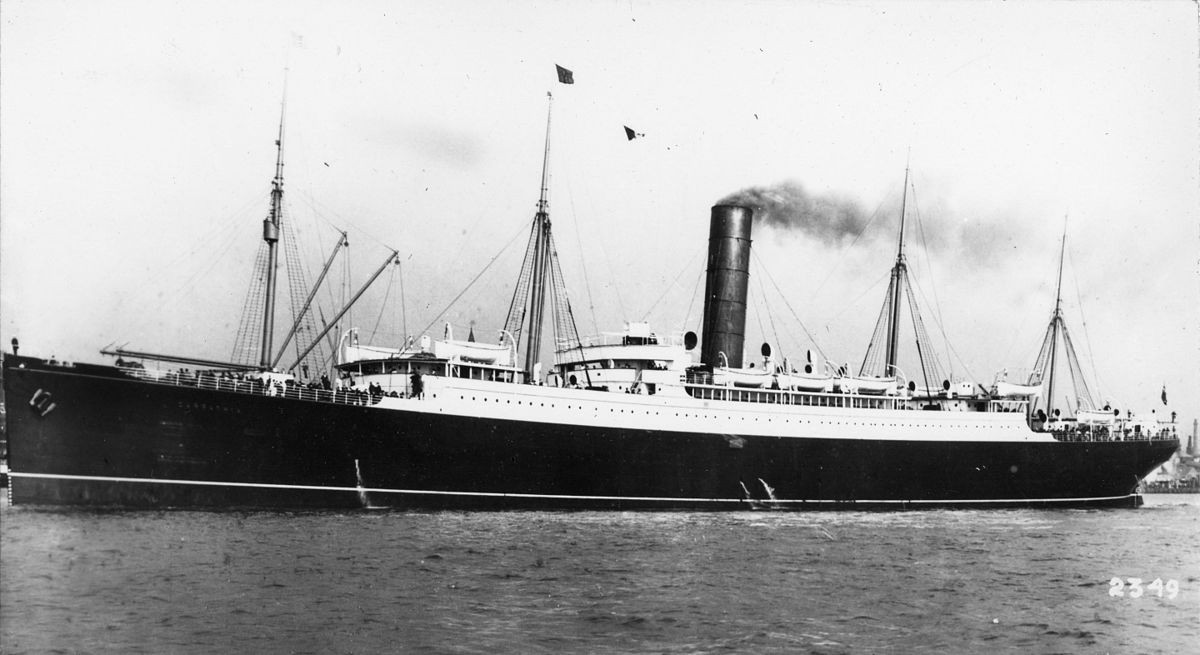

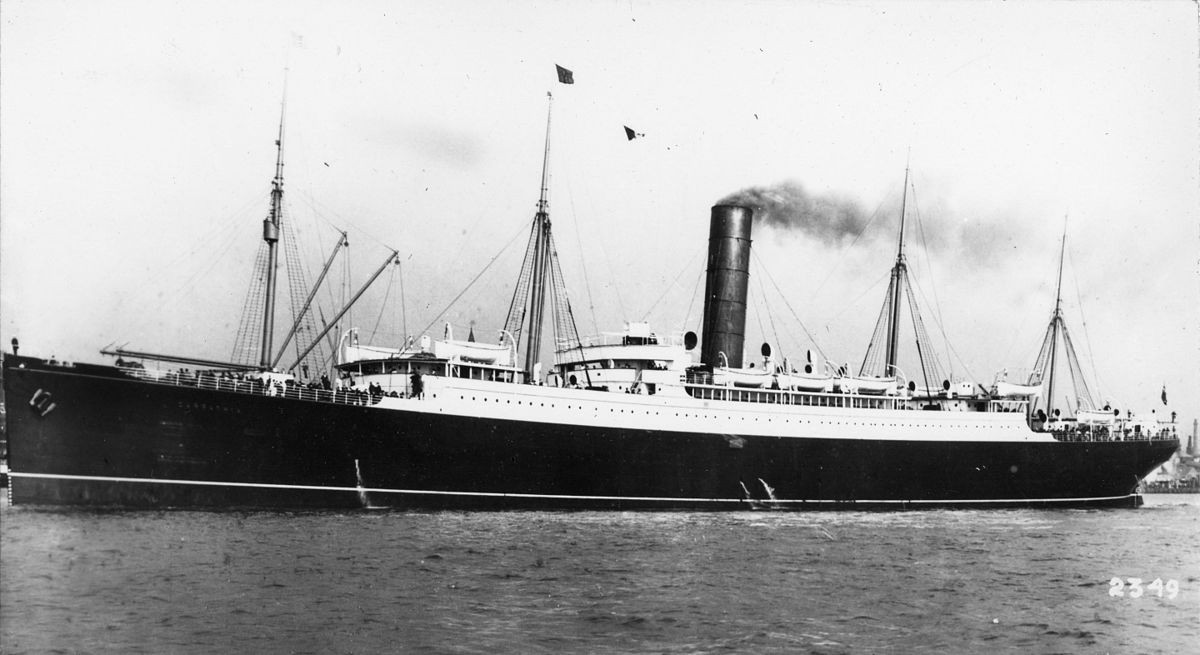

Photo: Unidentified Titanic survivors aboard Carpathia.

Get real-time email alerts when new unrolls are available from this author!

Twitter may remove this content at anytime, convert it as a PDF, save and print for later use!

1) Follow Thread Reader App on Twitter so you can easily mention us!

2) Go to a Twitter thread (series of Tweets by the same owner) and mention us with a keyword "unroll"

@threadreaderapp unroll

You can practice here first or read more on our help page!