ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/c…

iopscience.iop.org/article/10.108…

developing states that economically depend on coastal tourism.

many – but not all – global tourism investments, as well as

environmental and cultural destination assets,

ipcc.ch/report/SRCCL

fao.org/giahs/backgrou…

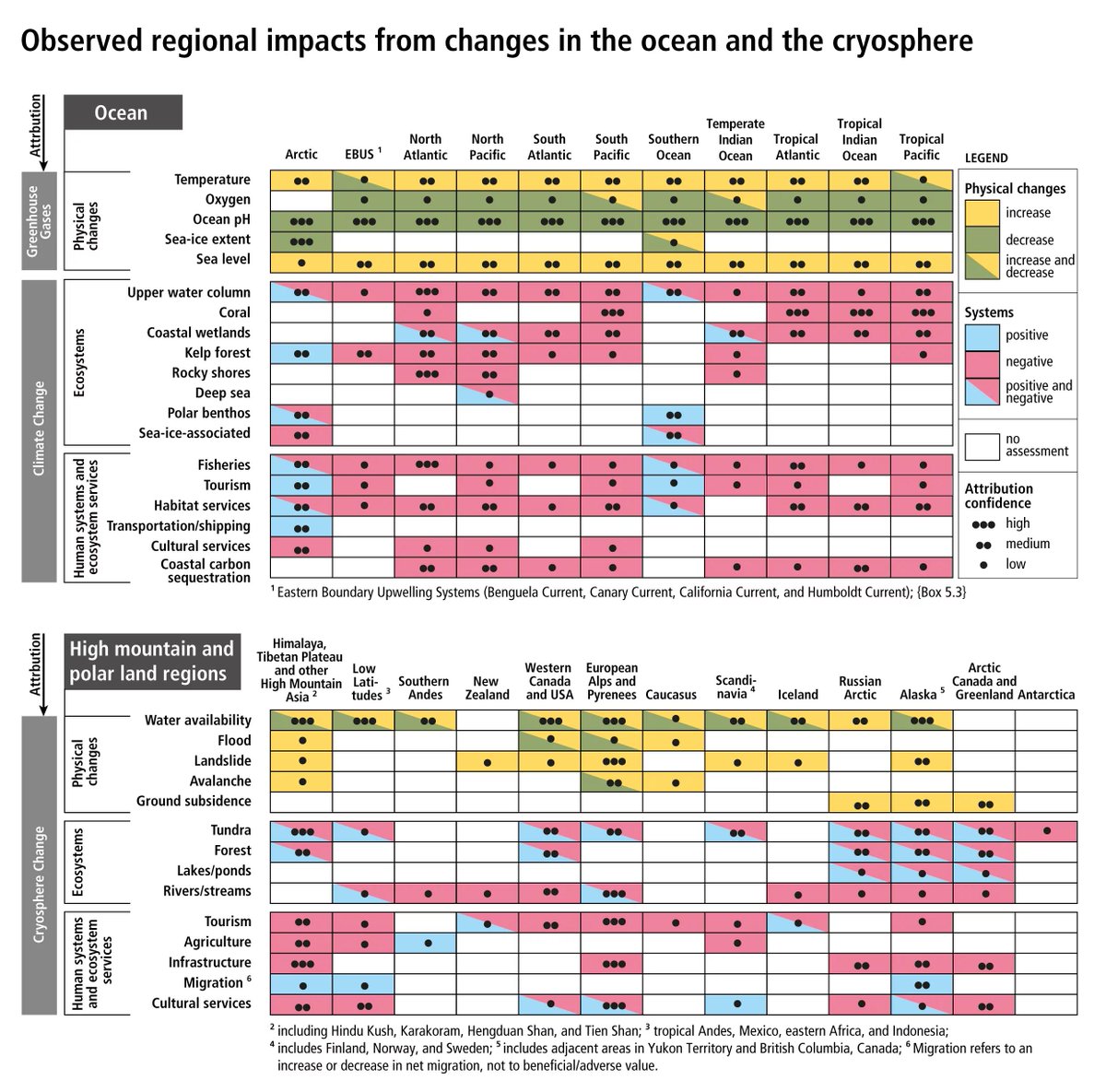

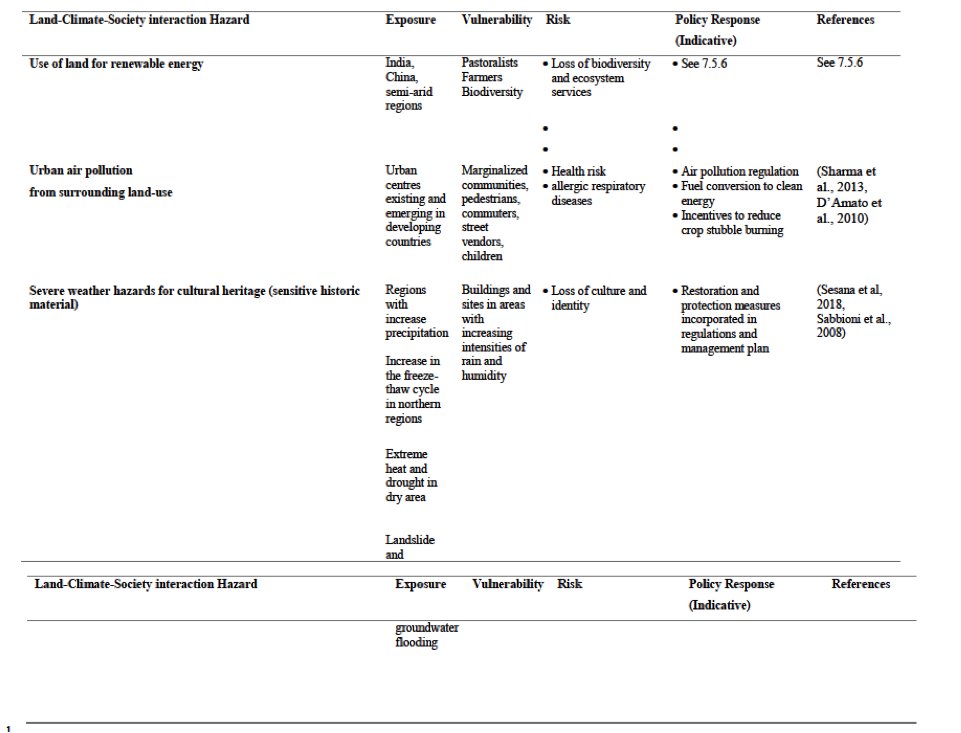

This report addresses loss and damage in relation to snow onset processes, including ocean changes and sea level rise, glacier retreat, and polar cryosphere changes, as well as rapid onset hazards such as tropical cyclones.

to address a wider perspective on impacts on human systems, for example, complementary to quantitative assessments of health impacts.

threats to cultural heritage, socialising activities, integration of marginalised groups and cultural

ecosystem services,

given society.

environmental and housing quality and healthy lifestyles),

link.springer.com/article/10.100…

to safer areas, gained traction in recent years

individual and community needs.

from examples of recent case of resettlements, and extend to loss of cultural heritage and indigenous qualities in the case of small island states.

changes in construction modes, sand mining and unsustainable resource extraction,

icomos.org/en/focus/clima…

including enhancing the connections between cultural heritage, climate change science and action.

- END -