As an executive and scientist, I look at COVID19 and see learning opportunities. My birth country, Canada, is very prepared. Why?

WHAT WENT WRONG IN 🇨🇦 DURING SARS?

(a thread on what we learned and why we're prepared)

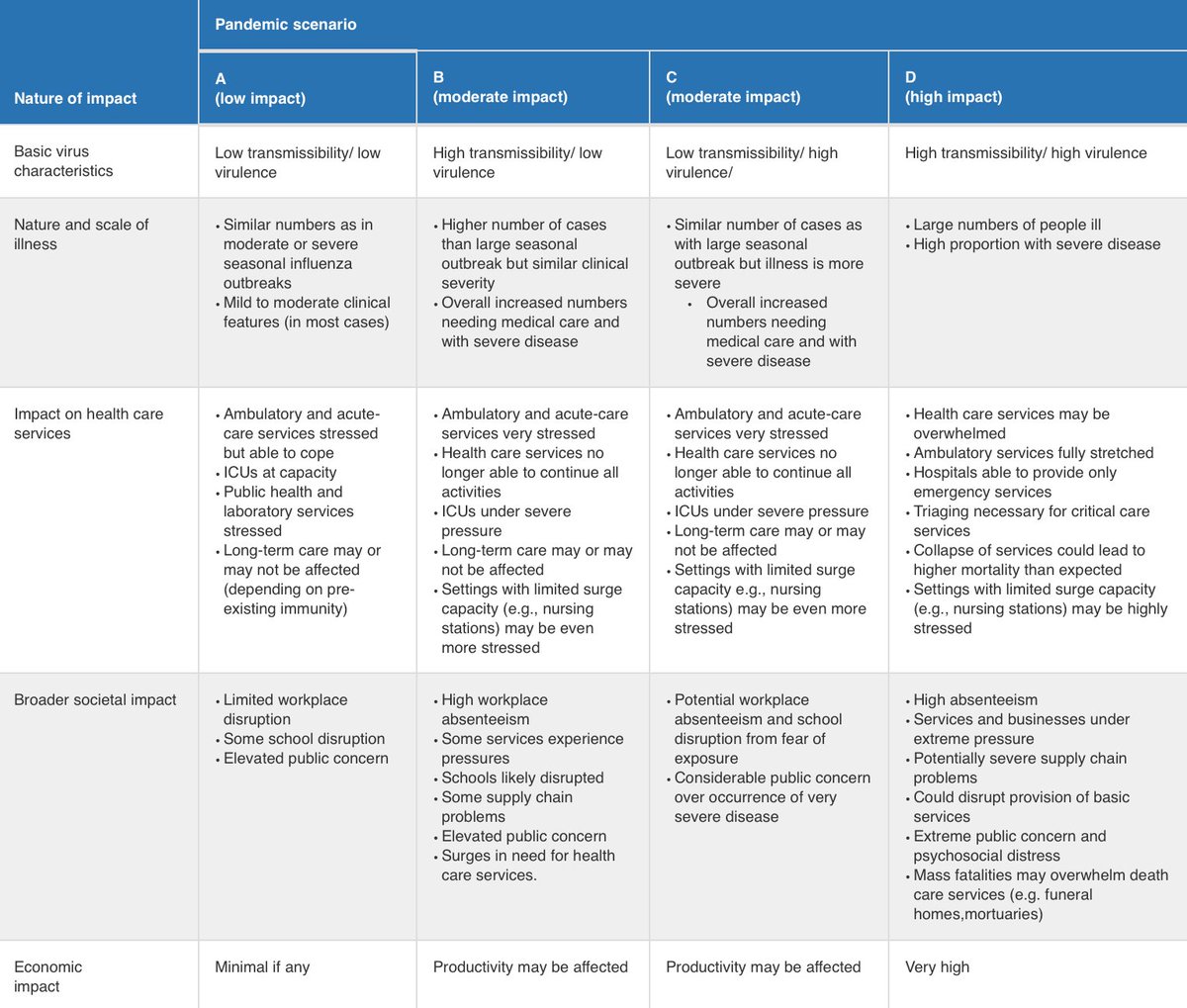

- Lack of surge capacity in clinical and health systems

- Difficulty with timely access to lab testing and results

- No protocols in information-sharing across government

- Unclear ownership of health data

- Lack of coordination across institutions to manage + respond to outbreaks

- Poor outbreak management protocols, infection control, and disease surveillance

- Weak links between public health and health services (hospitals, physicians, etc.)

Best practices were built off the CDC and Australian system.

- 1.5 MILLION N95 masks

- 165 emergency mobile 200-bed hospitals

- drugs and antivirals

I'm a startup founder now -- how is this relevant?

1. Learn from your mistakes. When something breaks, engage with what went wrong. Instead of assigning blame, look for systemic causes. How was what happened a symptom of a broken system?

Stay healthy!