Why doesn’t the stomach digest itself?

This question, raised on a recent episode of @thecurbsiders, has been asked for centuries.

The answer is so cool, and uncovers even more mysteries...

Let’s start with a question.

Which of the following is a mechanism by which our stomach protects its epithelial lining from gastric acid?

The resting luminal pH of the stomach is 4-6; when stimulated, the pH can fall below 1.

This results in a [H+] in the stomach more than a million-fold of that found in the blood!

Ok, but is this gastric acid corrosive?

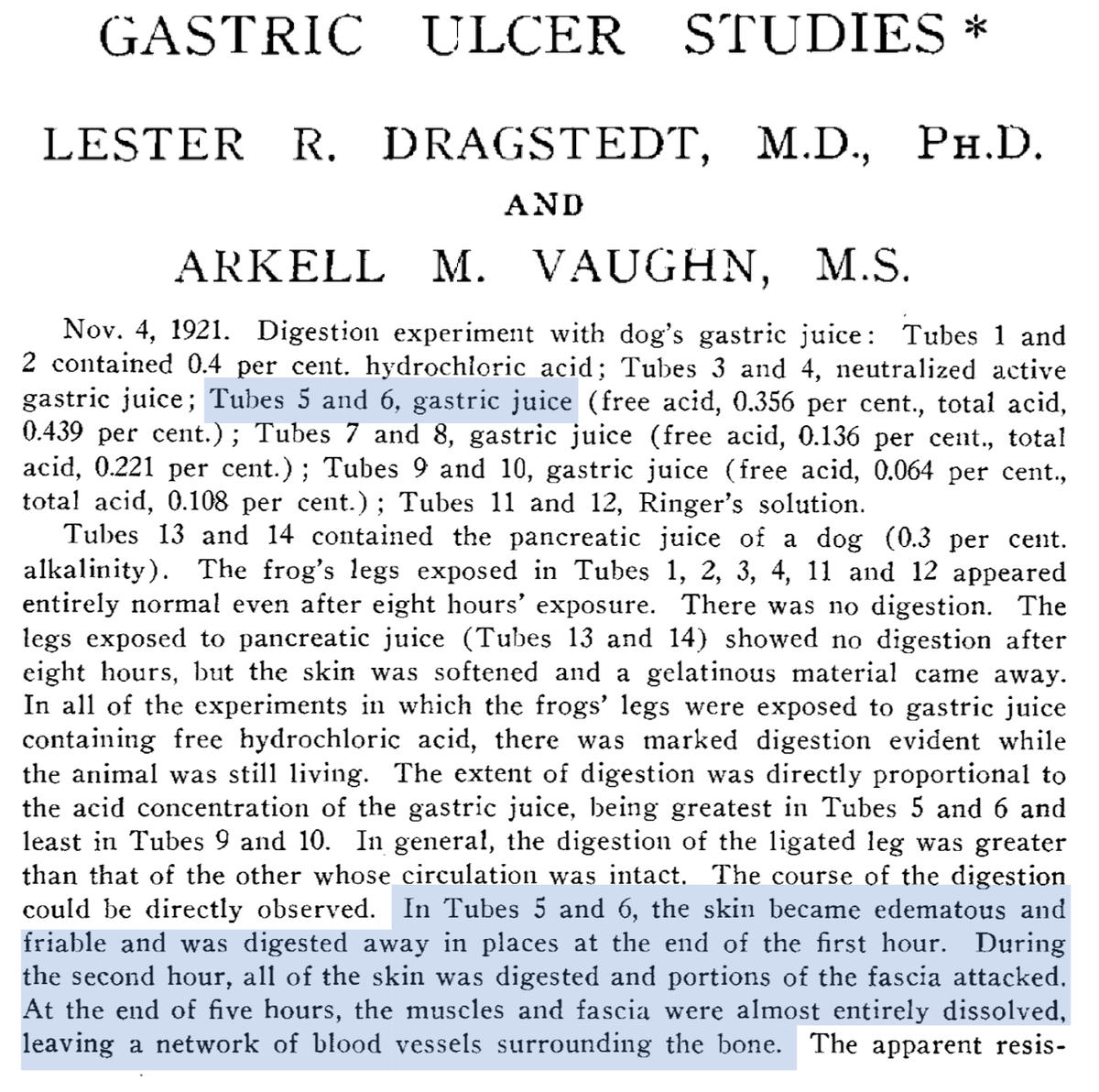

In 1924, Dragstedt and Vaughn suspended the legs of living frogs in gastric acid. They were promptly digested away.

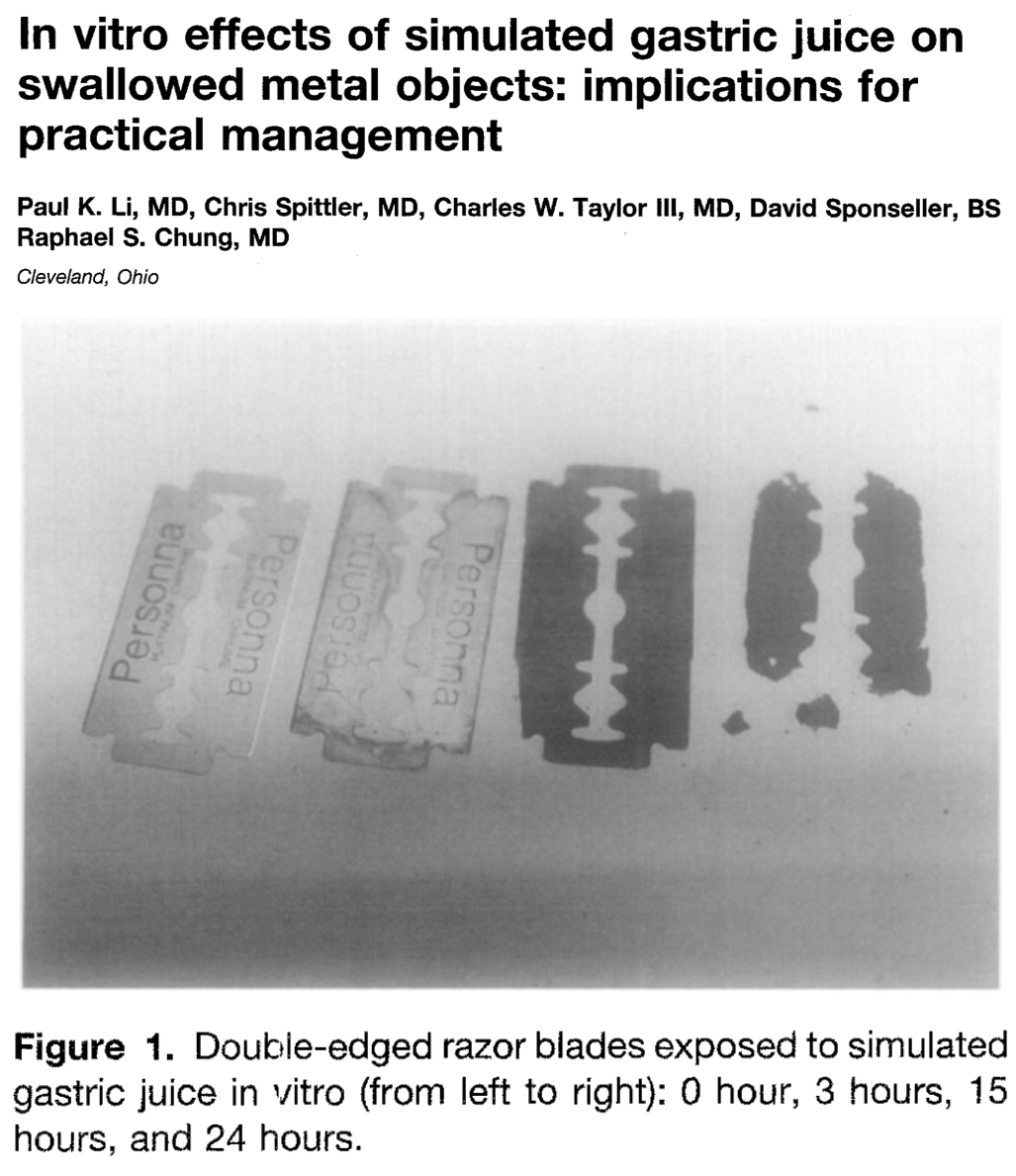

And it can dissolve razor blades, though more slowly.

jamanetwork.com/journals/jamas…

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9283866

So, yeah, the stomach “need protection". One explanation was offered in 1856 by Claude Bernard. He suggested that the mucus coating of the stomach was a barrier to acid, protecting the underlying epithelium.

He dubbed it the “porcelain vase”.

goo.gl/HdSjS3

Turns out Bernard was onto something right.

Good old fashion mucus (yes, like the stuff that comes out when we blow our noses) is a major reason our stomachs are not digesting themselves.

And what is gastric mucus? It is:

*made up of 5% mucin (a large glycoprotein) and 95% water, forming an

*unbroken viscous gel, with

*two layers (one loosely adherent, one firmly adherent), which are

*100-400 microns thick

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18549814

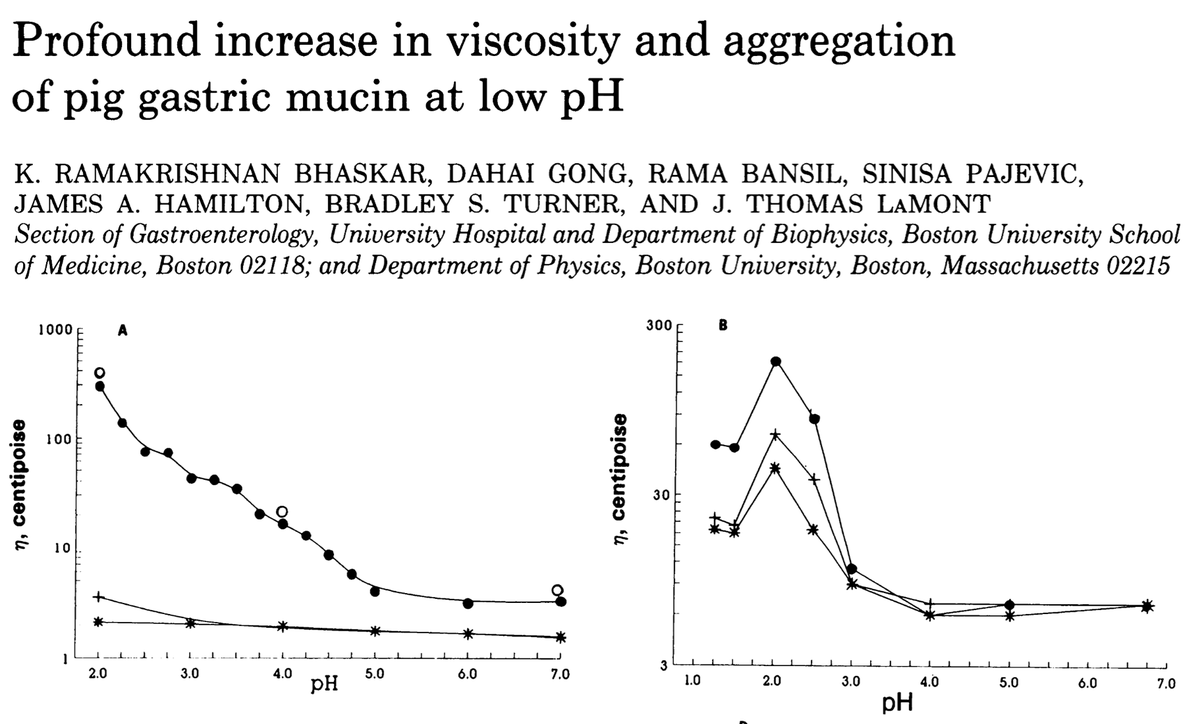

One (of the many) amazing things about gastric mucus: as the pH decreases from 7 to 2, there is a 100-fold increase in viscosity. This feature optimizes the mucus barrier at low pH.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1719823

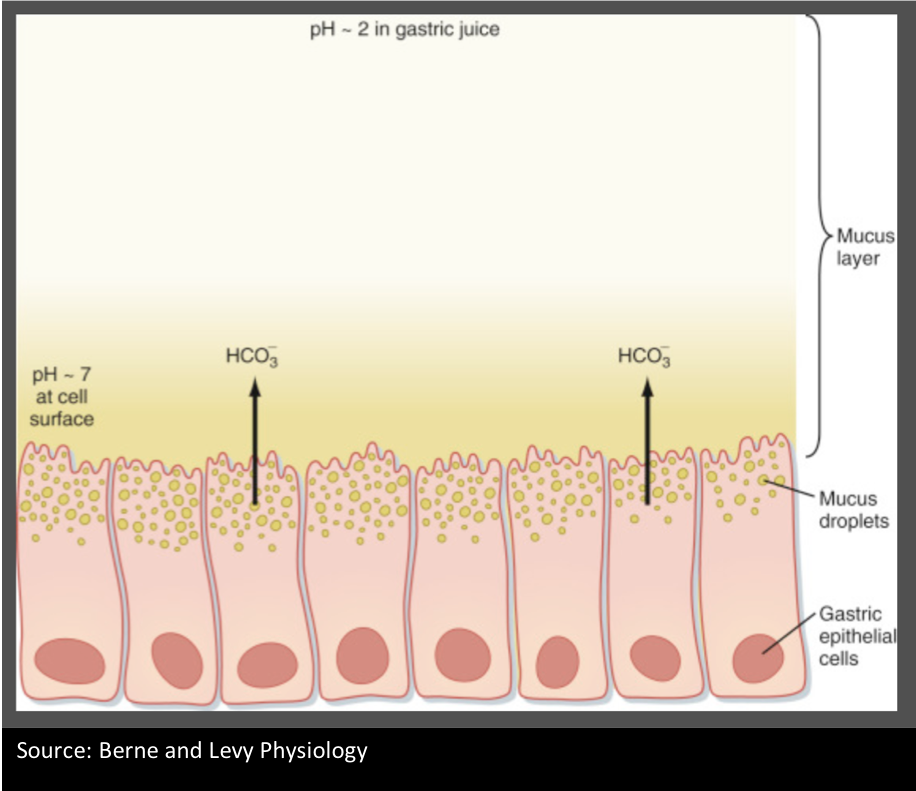

And how exactly does mucus (really, MUCUS!) protect our stomachs from their own acid? It:

*limits back-diffusion of acid and proteins (e.g., pepsin)

*contains bicarbonate, resulting in a pH gradient (high near the lumen, low near the epithelial cells)

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7076026

The barrier to acid back-diffusion results in part from a surfactant-like layer of surface-active phospholipid. Yup, the stomach appears to have its own surfactant.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6846549

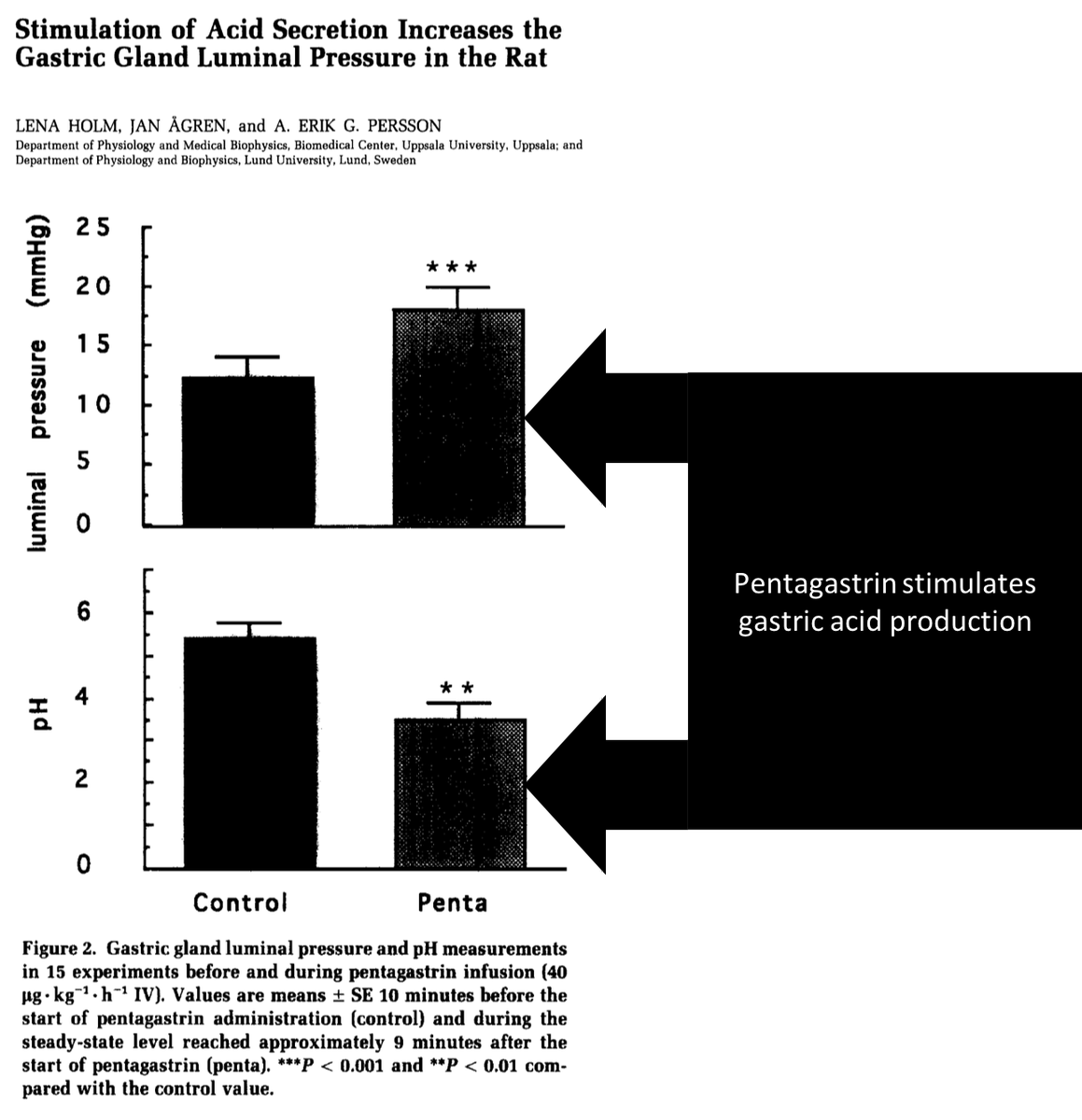

So here's the paradox: if the mucus is impenetrable and continuous, how does acid get from the parietal cells to the gastric lumen?

The acid is propelled by pressure! When acid is created, pressures in the gastric glands increase from ~12mmHg to 17mmHg propelling acid into the gastric lumen.

Apparently, hydrostatic pressures explain everything!

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1451973

When this pressurized acid (which has low viscosity) is injected into mucus (which has high viscosity), the acid penetrates the mucus, instead of diffusing.

This has been dubbed "viscous fingering” and may depend on the high pH of gastric mucus.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1448168

Subsequent studies have provided more details about the channels created by the propulsion of gastric acid.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11054387

Let's close with our original question:

Which of the following is a mechanism by which our stomach protects its epithelial lining from gastric acid?

Mucus is just one of the many features of the stomach that keep it protected from the harsh acid environment. The link below is a great review of the topic.

I hope this helped answer @thecurbsiders question!

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18923189