First, a question: why are urine antigen tests often used to diagnose apparently non-urinary infections?

[NS = nephrotic syndrome; SC = sieving coefficient]

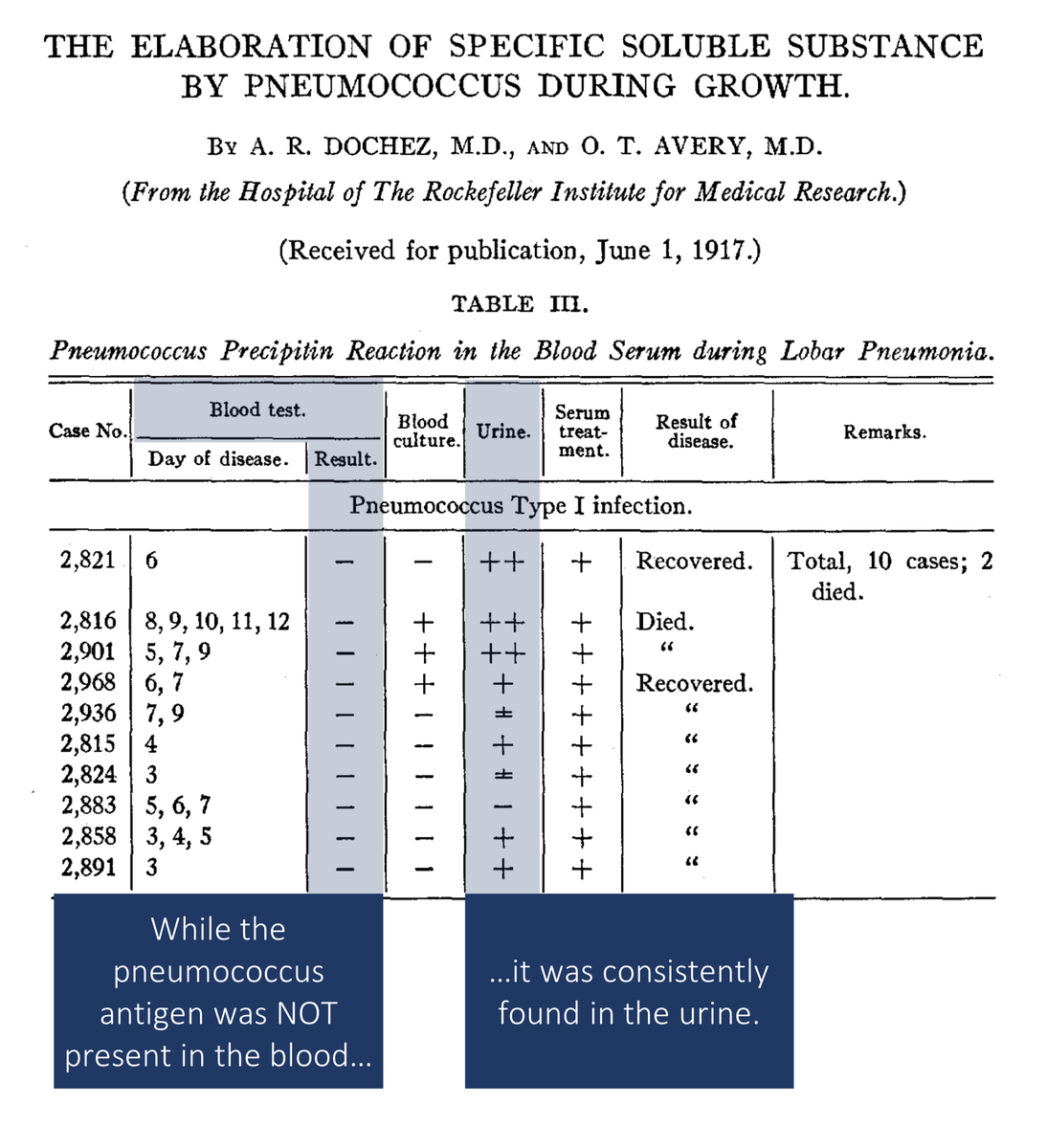

In 1917, Dochez and Avery observed that a pneumococcal antigen was readily identified in the urine of patients with lobar pneumonia, even when it couldn't be isolated in the blood.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19868163

These results from over a century ago raise two questions:

(1) How did this molecule get into the urine if pneumococcus doesn't itself infect the genitourinary system?

(2) If the molecule gets into the urine via the blood, why isn't the blood test positive too?

Before answering these questions, it's important to note that the molecule used in contemporary pneumococcal urinary antigen assays is the C-polysaccharide.

Cool fact: C-polysaccharide is what CRP "reacts" with, giving it its name, C-reactive protein.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19869788

In order for a molecule like to C-polysaccharide to make its way into the urine for use as a diagnostic test, two things must occur:

*filtration by the glomerular capillary

*incomplete reabsorption by the renal tubules

Notice that sodium is completely filtered, while almost no albumin is filtered.

Based on the fact that C-polysaccharide is used as a urinary antigen for the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia, which of the following are reasonable estimates for the molecular weight and SC?

C-polysaccharide is small enough to be filtered by glomerular capillaries and therefore can be picked up by urinary antigen tests.

But, why don't we just assay the blood?

One clue comes from another freely filtered polysaccharide...

...INULIN!

Urine concentrations of inulin are much higher than plasma concentrations. It's possible that small microbial polysaccharide antigens have similar relative concentrations. Result:

Urine antigen test: positive

Plasma antigen test: negative

C-polysaccharide isn't the only small molecule antigen used for diagnosis. Others include legionella, histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, among others.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24856525

It's worth noting that other advantages of urine exist. It is:

*easily acquired non-invasively

*large volume

*able to be concentrated

Before summarizing, ask the original question one more time:

Why are urine antigen tests often used to diagnose apparently non-urinary infections?

[NS = nephrotic syndrome; SC = sieving coefficient]

To summarize:

⭐️many urinary antigens are small, with high sieving coefficients

⭐️this leads to their presence in the urine at high concentrations, even if the organism isn't isolated in the urine

⭐️plasma concentrations may remain low, with resulting negative assays