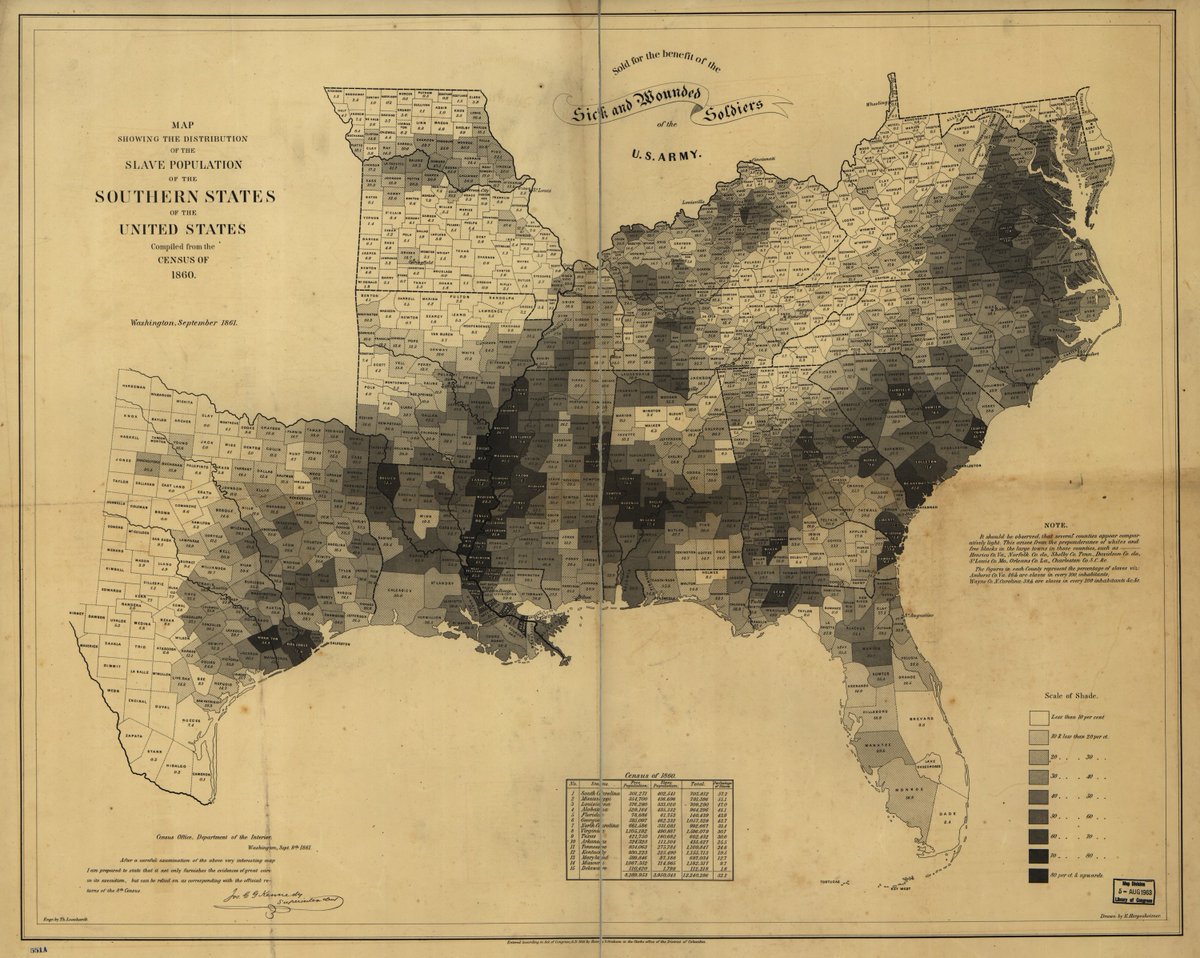

"Mapping the Nation: History and Cartography in Nineteenth-Century America” by Susan Schulten: books.google.com/books?id=YSEwY…

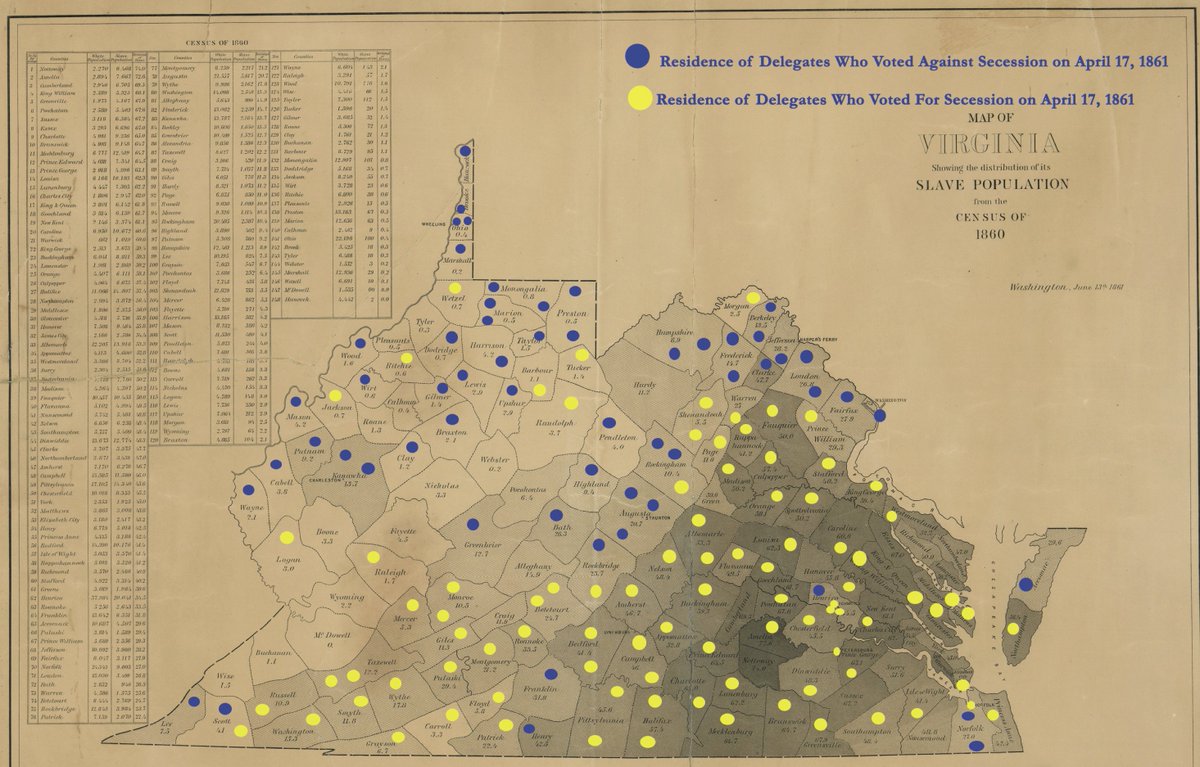

"The Map That Lincoln Used to See the Reach of Slavery” by @rebeccaonion: slate.com/blogs/the_vaul…

“Mapping Slavery” from the Library of Congress: blogs.loc.gov/loc/2012/10/ma…