It was a major World War II operation by the Polish underground resistance, led by the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), to liberate Warsaw from German occupation.

The plan was intended both as a political manifestation of Polish sovereignty and as a direct operation against the German occupiers.

"No doubt Warsaw already hears the guns of the battle which is soon to bring her liberation...

In Polish-controlled territory, during the first weeks of the Uprising, people tried to recreate the normal day-to-day life of their free country.

By mid-August most of the water conduits were either out of order or filled with corpses.

In addition, the main water pumping station remained in German hands.

By the end of September, the city center had more than 90 functioning wells.

Berling's Polish Army losses in the attempt to aid the Uprising were 5,660 killed, missing or wounded.

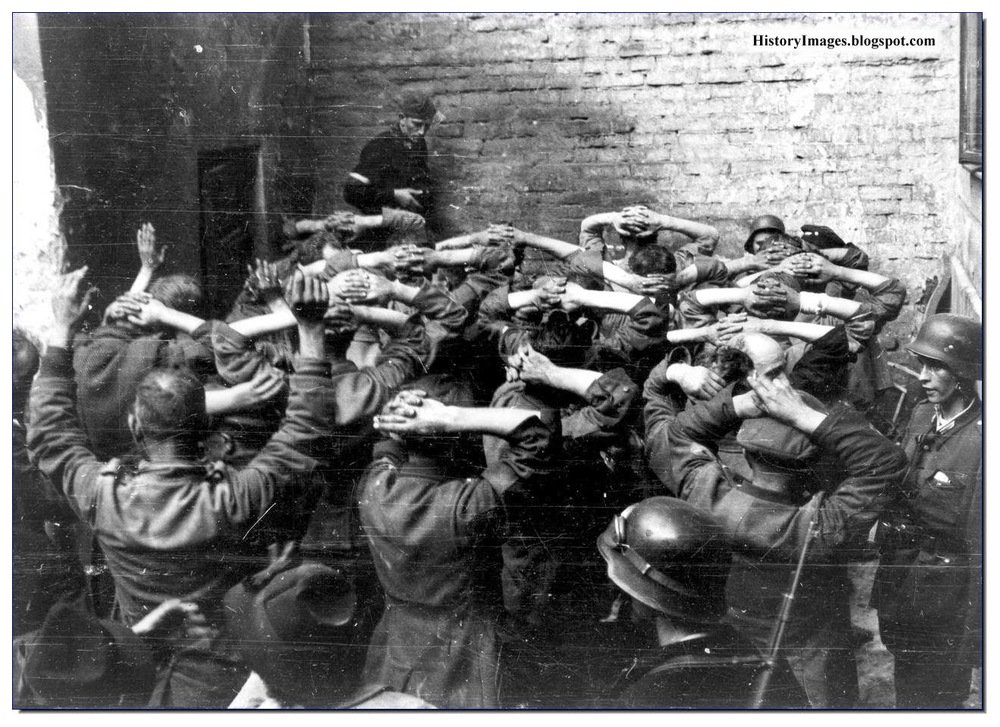

Between 5,000 and 6,000 resistance fighters decided to blend into the civilian population hoping to continue the fight later.

— SS chief Heinrich Himmler, 17 October, SS officers conference

It was soon included as a part of the great Germanization plan of the East; the genocidal Generalplan Ost.

After the remaining population had been expelled, the Germans continued the destruction of the city.

According to German plans, after the war Warsaw was to be turned into nothing more than a military transit station, or even an artificial lake.

— George Orwell, 1 September 1944.

They were interrogated and imprisoned on various charges, such as that of fascism,

Between 1944 and 1956, all of the former members of Battalion Zośka were incarcerated in Soviet prisons.

President Roman Herzog, on behalf of Germany, was the first German statesman to apologize for German atrocities committed against the Polish nation during the Uprising.