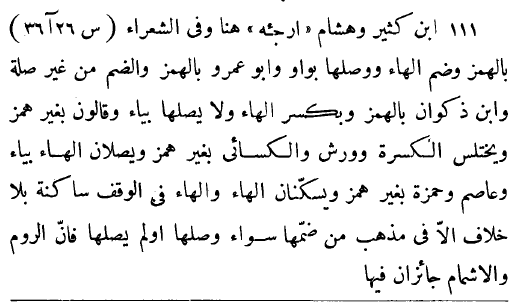

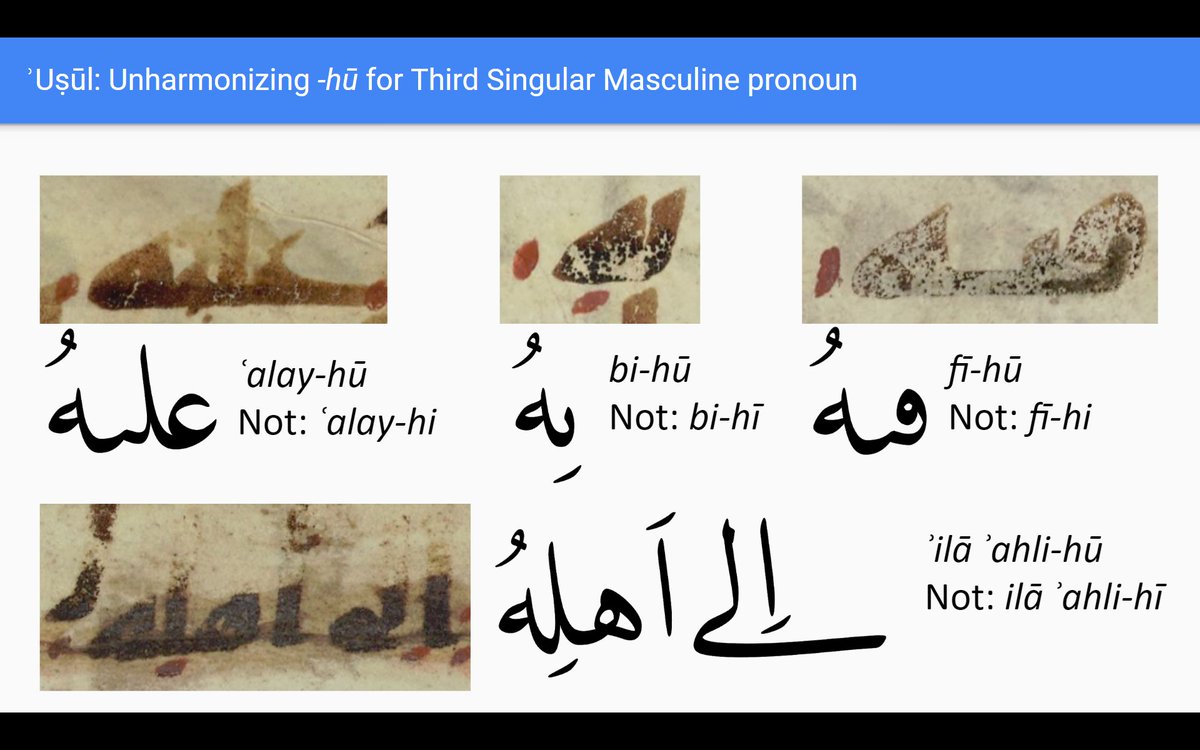

humū, ʾantumū, ʾilay-kumū, ʿalay-himū etc. This is absolutely regular and must be applied consistently if following his reading.

Hafs reads: ... li-ʾahaba ... “I am but a messenger of your lord, so that I will give you a pure son”

Warsh reads: ... li-yahaba ... “[...] so that he will give [...]”.

So how do we learn more?

doi.org/10.1163/187846…

academia.edu/41060428/Arabe…

academia.edu/36426137/Cella…

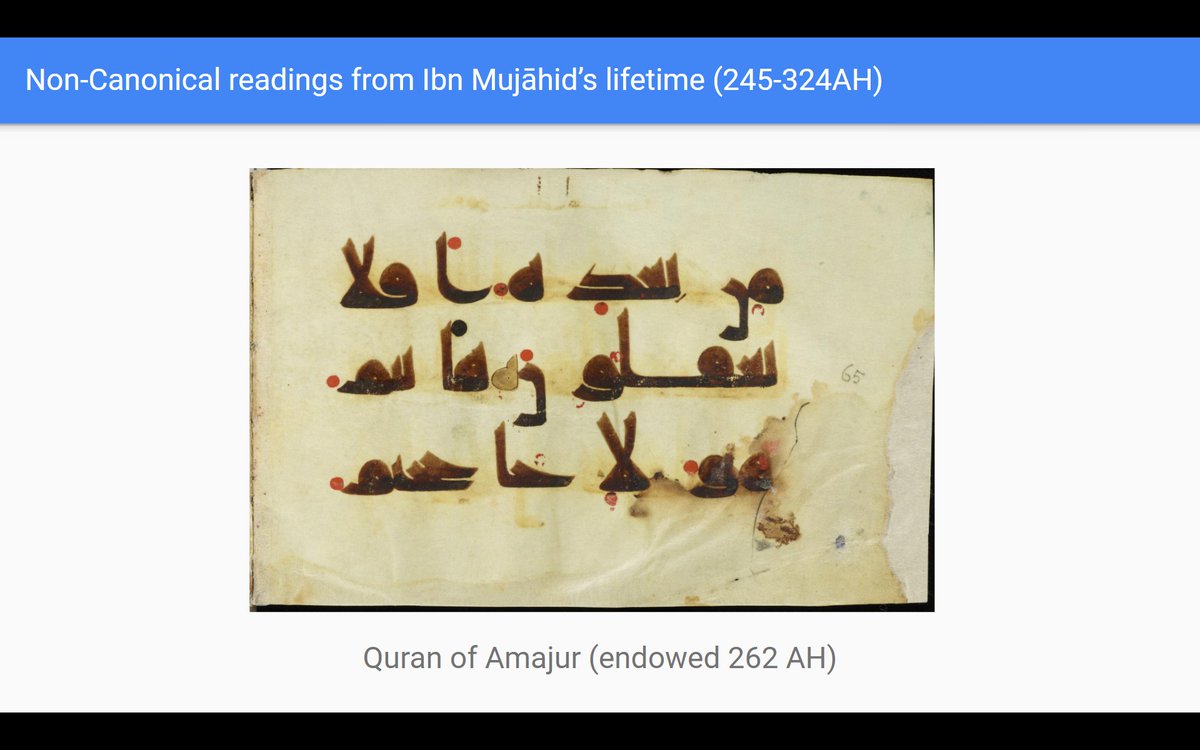

However, Uthmanic non-canonical readings were very common!

While traditionally popular readings like ʾAbū ʿAmr and Warš ʿan Nāfiʿ occurs a lot in these manuscripts, this mystery reading clearly occurs way more often than Ibn Kaṯīr for example.

cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01…

The tradition gives 20 mutually exclusive answers as to what that language is, and manuscript are set to bring many more conflicting answers.

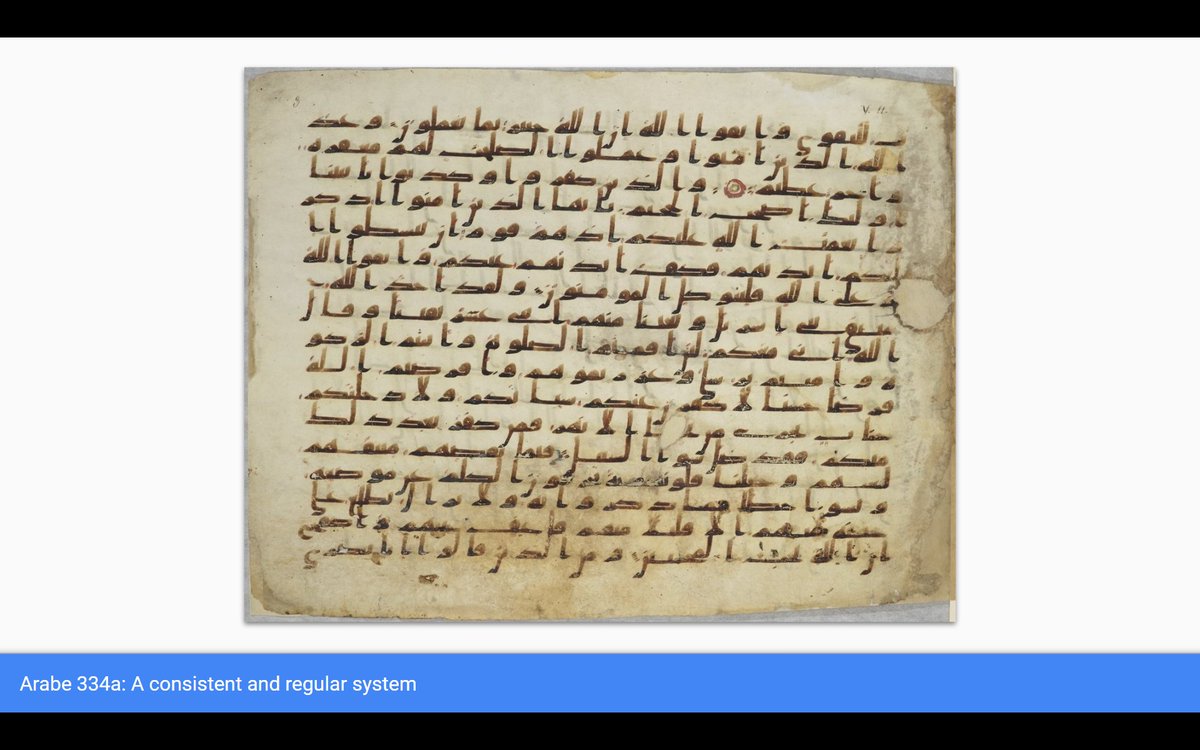

Arabe 334a: gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv…

Arabe 330f: gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv…

Arabe 329d: gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv…

Or. 6184:

hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:15…

Landberg 834: resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB000092DF000…