Where are all the aliens?

Then imagine *how much more* energy a more advanced civilization would be using, and radiating.

The main explanations I've seen tend to be a bit grandiose:

Perhaps intelligent life really is incredibly rare? Perhaps we're alone?

Perhaps civilizations destroy themselves too quickly to send out a lasting signal?

The Sun puts out 3.486 × 10²⁶ watts of energy.

All the electricity generators on Earth have a capacity of about 7.5 x 10⁹ watts.

ag.tennessee.edu/solar/Pages/Wh…

When he was born, electrical grids were in their infancy (one of the first was built near his home in Rome 19 years before his birth).

Signals at that end of the spectrum stand a far better chance of getting picked up by extraterrestrial observers, because there's less background noise in the universe at those frequencies.

If we watch I Love Lucy, it's on cable-delivered streaming services which don't leak radio signals.

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

arxiv.org/abs/1410.7796

If you point a really strong radio beam in just the right direction, surely that's detectable?

Well, yes. But consider the problems.

But while you can transmit a powerful signal for a short time quite easily, the energy consumption of a long-lasting "beacon" quickly becomes, er, astronomical.

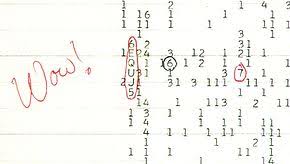

The Wow! Signal is a very odd transmission in the radio "water hole" picked up in 1977: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wow!_sign…

But there was also just one Arecibo Message, and it definitely happened.