No, really. nationalreview.com/corner/new-dea…

(For those of you who are as bad at dates as he is, the late 1960s and early 1970s were three decades *after* the New Deal of the 1930s.)

His column does nothing to address my points about the 1960s and 1970s, but I'll humor him and head to the 1930s.

This is *sort* of a big theme in the prevailing literature on the New Deal. We talk about it a lot.

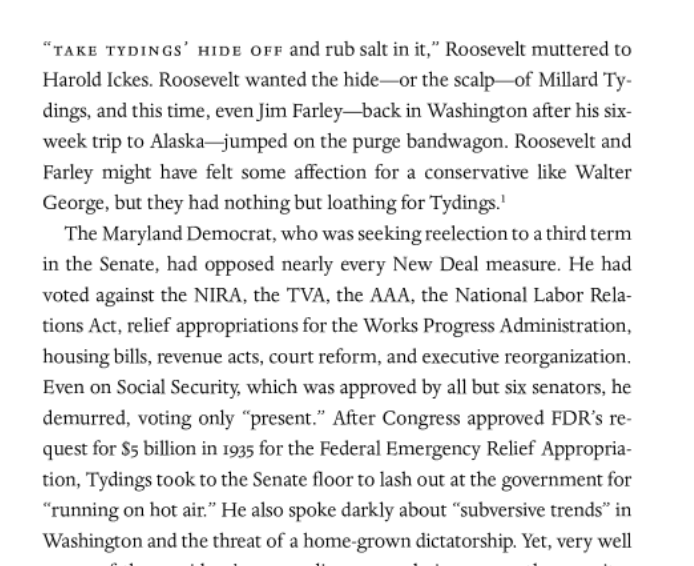

Modern conservatism *was* taking form in opposition to the New Deal, but it was a thoroughly bipartisan effort in the 1930s.

Again, historians have been talking about this for quite a long while.

Here's a @JourSouHist article from 1965:

Asked if FDR hadn't proven to be his own worst enemy, Cotton Ed Smith retorted, "not as long as *I* am alive."

After WWII, this conservative coalition only picked up steam:

But closer to home, he should also check out the National Review archives.