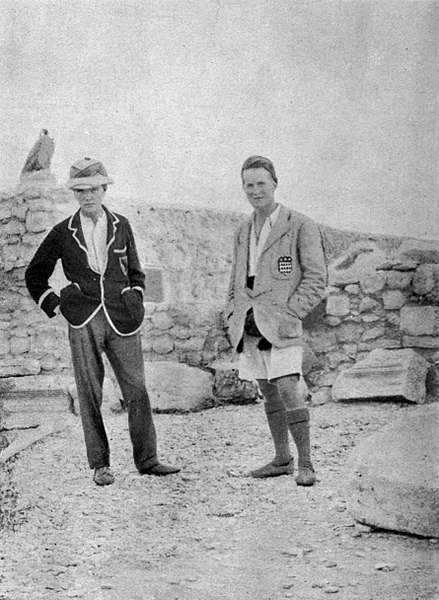

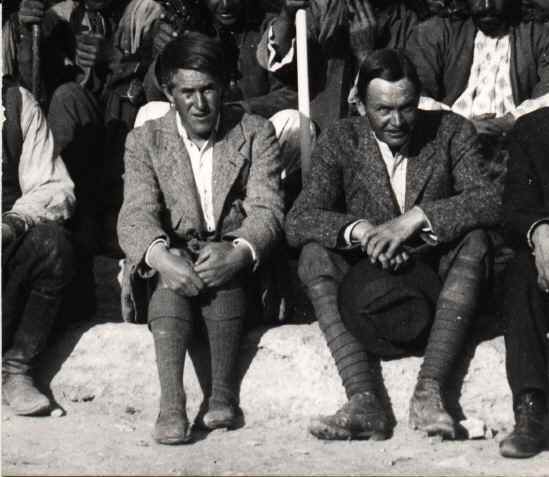

(Leonard Woolley (left) and Lawrence in their excavation house at Carchemish, c. 1912)

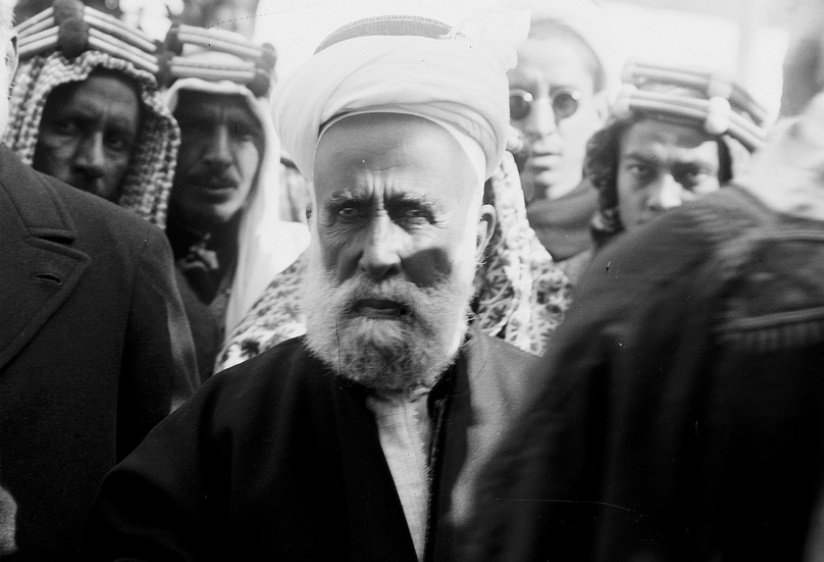

In November, it was decided to assign S. F. Newcombe to lead a permanent British liaison to Faisal's staff.

Working closely with Emir Faisal, he participated in and sometimes led military activities against the Ottoman armed forces, culminating in the capture of Damascus in October 1918.