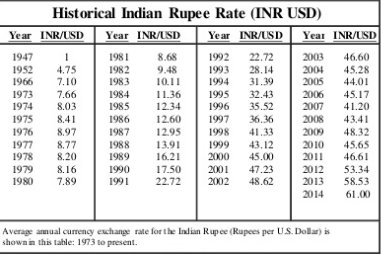

But this fall in the rupee has coincided with one of the strongest phases of the Indian economy ever

An economy growing at a faster clip than it ever has in the past 4000 years

How can the economy be doing so well at a time when the country’s monetary unit is at its weakest.

Most intelligent people would have this gut-feel that a country’s economic health mustn’t be judged by the state of its currency unit, but they may struggle to articulate why people who feel otherwise are wrong

Reflection and deliberation are not in vogue

What is the history of the Rupee?

When did India move to a fiat currency? What are the problems in attempting to manage the value of currency unit while not maintaining the discipline to rein in inflation?

An examination of the history of the Rupee illustrates that monetary economics is a moral minefield. It is not possible to have the cake and eat it too.

So let’s examine the history of currency in India

Magadha coin

(25 mashakas - 5th cen BCE)

Source : coinindia.com

The Arthasastra is also interesting as it has the first clues to the etymology of the modern word “Rupee”

The silver coins manufactured by the mint are referred to as “rūpya rūpa”. In Sanskrit, rūpya means “wrought silver” and rūpa refers to form / shape

One is not sure of the actual silver content in it.

Similarly tamra rupa comprises of four parts of an alloy named “pAdajIvam”

vyavahArikim : Medium of exchange

Koshapraveshyam : Legal tender admissible to the treasury

Kautilya also talks of a seigniorage of 8% levied on new coins issued - referred to as “rūpika” - a source of revenue to the treasury

Judging by the coins associated with the great Gupta Empire of 4th-5th century CE, it does seem that Gold coins were a LOT more common in the Gupta Empire relative to the Mahajanapada or Mauryan periods

Source: coinindia.com

There was a radical change in monetary standards introduced in India with the coming of Muslim rule after the 12th century (at least in North India)

The earliest conqueror of the North Indian plain was Muhammad Ghūri in late 12th cen

His gold coin issues were adhering to convention with goddess Lakshmi on one side and the name of the ruler on the reverse

The Delhi Sultanate established a firm equation between Gold and Silver of 1 : 10. A bi-metallic standard of sorts, that we didn’t quite encounter in earlier classical literature

The Khilji and Tughlaq Sultans were notorious for their raids on Hindu temples - which inevitably meant a great deal of Gold acquisition, and subsequent use of that Gold by the mint to issue coins

Gold predominated in the general circulation, because of which the unofficial exchange rate between Gold and Silver dropped as low as 1:7, though the official rate was at 1:10

A 15th century Persian revenue manual suggests that the royal treasury at Tabriz had more Gold sourced from India than from any other source

It was clearly a policy that promoted certain trade patterns which suited the tastes of the Muslim rulers - funded by Indian Gold

While Southern India, less influenced by the monetary chaos in the North, stuck to Gold currency with the Gold coin going by the name “Pagoda” in the Vijayanagar Empire

He established a tri-metallic coinage with strict standards after centuries of debasement -

The Mohur : Gold coin

Dam : Copper coin

The standards were imposed uniformly across the empire.

Dr BR Ambedkar, a fine monetary historian in his own right, speaks positively of the monetary discipline during Mughal rule in his work - “The Problem of the Rupee” published in the 1920s

Plus there were gold and copper coins as well in circulation - a legacy of Mughal and Vijayanagar rule

1835-1893 : Silver standard

1893-1898 : Transition to Gold standard

1898 onwards : Gold exchange standard

So clearly the Silver standard was effective for the longest period

For the first time the economy was not entirely or primarily self-contained as in earlier centuries, but foreign trade (particularly trade with Britain) increasingly constituted a large part of economic activity

But the move to Silver standard meant that the two countries were on different standards, and the govt made futile efforts to fix a ratio between the two

But this proved problematic when new Gold deposits were discovered in Australia and California in US, bringing down the Gold price

This resulted in vast accumulation of Gold in the Indian treasuries

- Demonetization of silver in many countries (Germany, Scandinavia in 1870s)

- Discovery of new silver mines

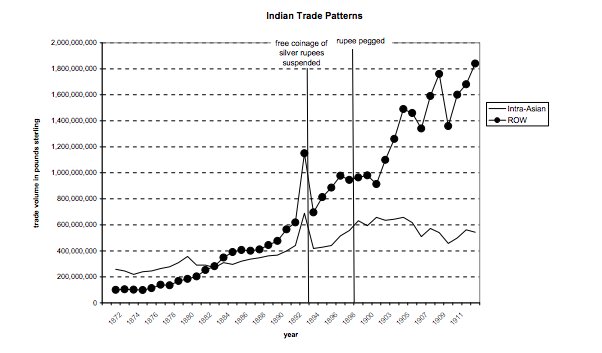

Source: citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/downlo…

Inflation in India remained under control (atleast compared to the standards we are used to in our times)

But these were the evils of colonial rule. Not so much the fall in the Rupee per se.

Fixed exchange rate

Free capital movement

Independent monetary policy

But this naturally meant a surrender of monetary independence and a monetary policy ill suited to the Indian business cycle

In later decades the low volatility of exchange rate was maintained despite some depreciation forced by crises.

A period of relative isolation from the world - a huge opportunity cost paid by the economy

Source: slideshare.net/MaAnU16/the-jo…

Currency pegging came at the cost

And even though we had barriers on trade & capital flows for most of the post independence years, we still had to buckle under pressure to devalue the rupee in 1966 - when we faced our first severe economic crisis

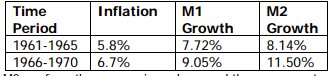

But inflation went out of control in the 60s, making Indian goods extremely expensive abroad

Source: ccs.in/internship_pap…

But things came to a head in 1966 when aid was cut off and India was forced to devalue its currency.

The reforms were forced upon India in part, by an IMF bailout.

Yet the Indian economy has strengthened by the day. Today it is the strongest that it has ever been, at precisely the moment when the Rupee is arguably the weakest it has ever been

That's not an anomaly at all

But it does not behoove the govt to prop up the rupee

The value of the Rupee is best left to the market.

Indian Numismatics history: coinindia.com

Arthasastra : archive.org/stream/Arthasa…

hkrdb.kar.nic.in/documents/Down…

hkrdb.kar.nic.in/documents/Down…

archive.org/details/in.ern…

JL Laughlin on 19th cen Indian monetary history:

journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10…

citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/downlo…

Post independence Rupee trends:

slideshare.net/MaAnU16/the-jo…

CCS piece on 1966 crisis:

ccs.in/internship_pap…

Thought I'd conclude with the image of the first silver "rupaiya" issued by Sher Shah in the 1540s

Had originally planned to include it while discussing Sher Shah's reforms

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sher…